March 09, 2022

Ketanji Brown Jackson

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Back in the days when a proper meal for a Supreme Court justice was a steak, a baked potato, a couple of shots of bourbon, and a cigar, nominees to this lifetime job weren’t expected to last all that long. For instance, Harry Truman’s four picks spent an average of only eleven years on the highest court.

But over time the stakes have been elevated to Battle of Stalingrad proportions due to a combination of a more activist judiciary and extended lifespans. The seven justices selected by Reagan, the elder Bush, and Clinton averaged 27 years, with Clarence Thomas still ticking.

The Supreme Court will likely decide upon the constitutionality of affirmative action at universities in 2023. But many would prefer that the existence of racial preferences not be even thought about when assessing the career qualifications of Joe Biden’s nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson, who was chosen out of all the black women in the country. (No one else need apply.)

Thus the media erupted in outrage when Tucker Carlson impudently pointed out that if Judge Jackson Brown really is “one of the top legal minds in the entire country,” then “it might be time for Joe Biden to let us know what Ketanji Brown Jackson’s LSAT [Law School Admission Test] score was.”

In a culture where diversity quotas are common but unmentionable, it’s natural to wonder what their effect is on hiring and thus ask for some objective evidence. We’ll probably never know in the case of Judge Brown Jackson, but working through the math about black women lawyers reveals much about affirmative action, something that even Supreme Court justices don’t appear to have fully thought through.

Logically, Tucker’s ploy was a rather nifty tactical trap sprung upon Judge Brown Jackson’s supporters. If they argue that she is such an exceptional black woman that she hasn’t needed racial preferences to get where she is in her career, that Joe Biden isn’t going to waste one of his precious Supreme Court nominations on some quota case who will routinely get out-argued by the other justices, well, that raises obvious questions about the downsides of affirmative action.

Or they could proudly celebrate Brown Jackson as a living exemplar of how, even in this complex modern world, the less qualified can still do okay. For instance, look at Lisa Cook, Biden’s black woman nominee to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Sure, her most celebrated paper is confused, but she’s being nominated to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and you’re not.

But of course Carlson’s critics were never going to pick one or the other of the two logical possibilities. Instead, they screamed:

Q. How dare Tucker ask for a black woman’s LSAT score when he didn’t ask for the score of a white man like Neil Gorsuch or Brett Kavanaugh?

A. White men don’t get affirmative action. Black women do.

Q. Racist!

To avoid being called racist, we are supposed to be as ignorant as possible of how affirmative action has worked since the late 1960s.

Interestingly, Biden considered only black women because that was the demand of power broker Rep. Jim Clyburn (D-SC), who saved Joe’s faltering run for the Democratic nomination just before the crucial 2020 South Carolina primary. Clyburn was trying to get his favorite judge, fellow South Carolinian J. Michelle Childs, on the Supreme Court. Clyburn could have demanded a South Carolinian be nominated as his quid pro quo, but insisting upon a black woman is more in tune with these intersectional times.

It is illuminating to speculate upon what the press reaction might be to a Republican president agreeing to a key GOP congressman’s demand that he nominate only a South Carolinian. No doubt, it would be pointed out that South Carolina is a relatively small state and one with fairly low average LSAT scores. (The U. of South Carolina law school, where Judge Childs earned her J.D., ranks 92nd in LSAT scores.)

So, a GOP president who only allowed himself for political reasons to pick a South Carolinian would be criticized for drawing from a limited pool of talent. Likewise, Democrats have frequently accused Clarence Thomas of being dim because how many black Republicans were there to choose among? Of course, few dare say the same thing about Biden restricting himself to black women.

As it turned out, Clyburn’s Judge Childs was a bridge too far even for Biden.

In contrast to Childs, Judge Brown Jackson’s early years were more promising: She did well in high school debate, then went to Harvard College and Harvard Law School where she graduated cum laude. She then served three clerkships, eventually clerking for the Supreme Court justice she has been nominated to replace, Stephen Breyer.

How big a role did affirmative action play in her achieving that demanding role? Some, but likely not a huge amount. Justices only have four clerks, so they can’t afford sheer deadwood. Litigator Ted Frank estimates Breyer only hired a few black clerks:

Breyer didn’t have a lot of African-American clerks. I count 3 out of ~120, though I might be missing one or two from the last decade.

Fellow Clinton pick Ruth Bader Ginsburg hired only a single black clerk out of 119.

I asked Frank:

How do Supreme Court justices rationalize not applying affirmative action to themselves when hiring clerks? Because they know that deep down they, personally, couldn’t be biased? That, after all, they just want clerks who are smart, hardworking, and really into opera?

He replied:

I think it’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between affirmative action in theory (do outreach and then pick on merit; if all else is about equal, pick the underrepresented minority) and practice (anvil on the scale to achieve de facto quotas).

So if even very bright liberal Supreme Court justices don’t really grasp how the racial preferences they impose on other people (but not themselves) work in the real world, how can we expect anybody else to?

But after that high point of clerking for Breyer, Brown Jackson’s career stalled for a decade or more. She even wound up working as a public defender for a while. There have been many attempts to read ideological significance into that, but it strikes me as likely that, as a mother with two young children and a surgeon husband, she wanted a government job with reasonable hours.

In general, she seems like a nice lady, slightly less pathologically ambitious than the typical Supreme Court nominee.

Perhaps the most noteworthy issue on the Supreme Court’s agenda is affirmative action in higher education (and, by implication, in hiring). After 53 years of race-based discrimination, isn’t it getting to be time for the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to rule out choosing based on race? Indeed, back in 2003, the Supreme Court put a 25-year limit on the use of racial preferences by the U. of Michigan law school, and that will be up in only six years.

Moreover, anti-preference legal activists have hit upon the tactic of having Asians serve as the plaintiffs. White judges tend to find big institutions discriminating against non-whites harder to defend than discriminating against whites. Last month, for example, federal judge Claude M. Hilton ruled that Thomas Jefferson High School, the formerly 73 percent Asian STEM school in Virginia, was discriminating against Asians when it junked its entrance test in deference to the Racial Reckoning.

And, racial preferences remain strikingly unpopular with voters (not that they often get a say). In 2020 in deep blue California, an initiative to repeal California’s 1996 Proposition 209 banning affirmative action in state government was defeated 57–43.

As the years go by, defenders of race quotas double down on antiwhite antiquarianism as their excuse for why blacks haven’t caught up. For example, the Senate just this week passed the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act (and will hopefully move on to legislate against other scourges of our time such as tar-and-feathering, drawing-and-quartering, keelhauling, and the cat-o’-nine-tails).

On the other hand, most Americans aren’t aware of how big the racial gaps in cognitive ability are at the right end of the bell curve where the important jobs are.

The race disparity in talent is particularly glaring in the practice of law because much of it is so dependent on raw brainpower. There are a few legal specialties, such as plaintiff’s attorney, where personality matters tremendously. But the meat and potatoes of lawyering—writing contracts—is basically a medieval form of coding. Your job is to anticipate what could go wrong in a deal and write if-then-else statements to protect your client from those eventualities.

Blacks seldom strike it rich in Silicon Valley software, so it’s not surprising that they don’t do as well programming in Anglo-Norman English, either.

Law schools rely upon very simple measures to determine who is admitted, mostly LSAT score, college GPA, and diversity Pokémon points.

It could be that Judge Brown Jackson aced the LSAT test.

The LSAT is currently scored on a 120 to 180 bell curve scale, with a standard deviation of around 10. At Yale law school, the 25th percentile scores 170, the median 173, and the 75th percentile 176.

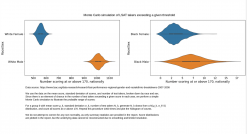

Nationally, 2013–14, whites averaged 153 and blacks 142, a 1.06 standard deviation gap. Men outscore women by about a quarter of a standard deviation.

Those aren’t enormous differences, but out at the right tail, from which they pick Supreme Court justices, the gap is wide.

An analyst sent me a Monte Carlo simulation of 2008–2014 data from the Law Schools Admission Council. Across the country, there would annually be about 1,000 white men scoring 170 or higher compared with 550 white women. And there would be about seven black men and three black women.

So it’s quite possible that Biden’s pick would have been one of those three in her year. After all, for the Supreme Court he only has to pick one black woman out of all the lawyers in the country, so he could well have found one who can do the job up to a reasonable standard.

But is this really the best way to run the country if we’re never supposed to even talk about it?