October 31, 2012

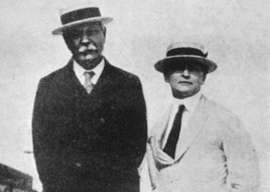

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini

With Halloween upon us as well as a new television program based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s writings, it’s worth revisiting his spiritualist leanings and his contentious relationship with Harry Houdini.

You probably think of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle as a buttoned-up sort of chap, the epitome of a Victorian English clubman with his richly tinted complexion and luxuriant waxed mustache.

Conan Doyle was all of these things and more. Apart from creating Holmes, he was also a historian, essayist, practicing doctor, pioneer amateur photographer, political candidate, paleontologist, motorist, athlete, spirited banjo player, and arguably the first man to popularize downhill skiing. In later years, Conan Doyle broke violently from the established church and became the proprietor of a popular freak museum that he opened, provocatively, next door to Westminster Abbey.

There was another side to Doyle that makes a striking contrast between the rational world of Holmes and the more shadowy one of Ouija boards and spooks. As a young provincial doctor in the 1880s, he”d regularly “consulted the cards” and attended séances. He described himself as “thrilled” when a dozen fresh eggs once apparently materialized in front of him out of the ether. Before long he was conducting experiments in mesmerism and telepathy, and over the years he became a firm believer in levitation.

Conan Doyle’s spiritualist beliefs eventually led him to endorse the claims of 16-year-old Elsie Wright and her 10-year-old cousin Frances Griffiths when they announced they had gone for a walk one day in the northern English village of Cottingley and returned with photographs of little people. The girls produced five such pictures, which Conan Doyle made the basis of his 1922 book The Coming of the Fairies. Sixty years later, the then-elderly cousins admitted that the whole thing was a hoax. They had cut out illustrations from Princess Mary’s Gift Book, in which Doyle himself had published a story, and propped them up in the grass with hatpins.

Across the Atlantic, Harry Houdini cast a more skeptical eye on the various phenomena produced by the 1920s” growing ranks of mediums and clairvoyants. He had known too many of these supposedly gifted performers when they were struggling vaudevillians to think otherwise.

For example, there was the Washington, DC husband-and-wife team of Julius and Ada Zancig, who convinced Doyle that they literally had a meeting of minds. After visiting the Zancigs, Doyle wrote that

The wife was able to stand with her face turned sideways at the far end of a room, and then to repeat names and duplicate drawings which I made and showed to her husband.

Houdini in turn visited and reported that the Zancigs

did a very clever performance. I had ample opportunity to watch their system and codes. They are swift, sure, and silent, and I give them credit for being exceptionally adept in their chosen line of mystery. Telepathy does not enter into it.

In April 1920, Houdini met Conan Doyle. They were arguably the two most famous entertainers on Earth, and each man quickly identified something he needed in the other. Houdini was then 46, had ambitions to be a writer, and never missed a chance to rub shoulders with the literary elite. Conan Doyle, 60, saw “the little chap” as a possible high-profile recruit to the spiritualist ranks.

A wary friendship began. Doyle announced that he was in regular touch with his son Kingsley, who had died in the Spanish flu pandemic two years earlier. On one occasion, he said, the family had been sitting around a table in a darkened room, “and I heard a very intense whisper say, “Father!,” and then after a pause, “Forgive me!””