January 27, 2009

Ben Bernanke Wants To Throw Dollar Bills Out of Helicopters

People who want to find out what Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben Bernanke has in mind for the economy need to read some history. Bernanke declares himself a “Great Depression buff,” and as a professor at Princeton, he published an entire book devoted to the subject. The work in question, Essays on the Great Depression, published by Princeton University Press in 2000, offers vital clues to his thinking. From his interpretation of this prior disaster, he draws a key conclusion: policymakers must at all costs prevent deflation. Unfortunately for the economy, Austrian business cycle theory gives us strong reason to reject both Bernanke’s historical analysis and his policy recommendations.

To understand Bernanke’s argument, though, we need to go back to an earlier book by an economist even more famous than Bernanke. Milton Friedman, the leading economist of the Chicago School, launched in the 1960s an all-out effort to defend the free market against its detractors. (Austrian School economists like Murray Rothbard contend that Friedman’s support for the market did not go far enough.) In a major battle in his campaign, Friedman challenged the prevailing Keynesian account of the Great Depression. As Keynes and his many followers saw matters, a free market might fail to generate full employment. Investors, in the grip of arbitrary “animal spirits”, can become skittish and reluctant to invest. If they do so, aggregate demand will not suffice to sustain full employment. Keynesians argued that the government must then step in to take up the slack. The ideal, if ideal it was, of laissez-faire, must be banished to the dust heap; government plays an indispensable role in keeping the economy stable.

Not so, said Friedman. In a famous book that he co-authored with Anna J. Schwartz in 1963 (also published by Princeton), A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1970, Freidman argued that the Great Depression did not stem from a fundamental flaw in capitalism. Quite the contrary, the blame rested on the government. Specifically, the Federal Reserve System began to deflate in 1928, in an effort to curb stock market speculation. The effort succeeded only too well, when the market crashed in October 1929. Even worse, the Fed, faced with bank panics in 1930 and 1931, contracted the money supply even further, beginning in March 1931. Here precisely lay the cause of the Depression: had the Fed instead expanded the money supply, the economy could readily have surmounted the stock market crash and the ensuing downturn. We could avoid Keynesian intervention, which in any case Freidman argued could not be timed to have the right effects. There was nothing amiss with the free market that correct monetary policy could not cure.

Keynes, by the way, anticipated expanding the money supply to cure depressions. In an open letter to President Roosevelt published in the New York Times, December 31, 1933, he said, “Rising output and rising incomes will suffer a set-back sooner or later if the quantity of money is rigidly fixed. Some people seem to infer from this that output and income can be raised by increasing the quantity of money. But this is like trying to get fat by buying a larger belt.” In Keynes’s view, more money will not by itself help if investors and consumers hoard it.

We need Friedman to understand Bernanke for a simple reason: Bernanke adopts and expands Friedman’s thesis. (Keynes hardly figures at all in Bernanke’s book.) We do not have to guess about this: in a tribute delivered in November 2002 to honor Friedman’s ninetieth birthday, Bernanke said: “Today I”d like to honor Milton Friedman by talking about one of his greatest contributions to economics … to provide what has become the leading and most persuasive explanation of the worst economic disaster in American history, the onset of the Great Depression, or, as Friedman and Schwartz dubbed it, the Great Contraction of 1929-33.”

In his own book, Bernanke faithfully follows the Master. Friedman and Schwartz concentrated on the United States; but when one takes into account the experience of other countries, Bernanke avers that the lesson that Friedman taught us gains further support. Specifically, countries that expanded their money supply, abandoning the gold standard in order to do so, recovered from the depression faster than those more reluctant to detach their currency from gold.

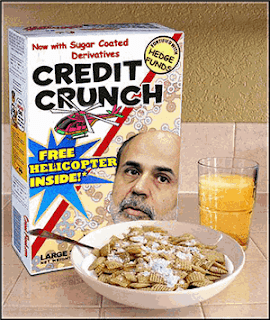

[Photoshop artistry by Bob Rooney]

As Bernanke shows himself well aware, a glaring problem confronts this account, which Friedman failed to solve. Why should a fall in the money supply cause the economy to collapse? So long as prices, including wages, can fall freely, will not the economy adjust to whatever amount of money exists? As Bernanke states the problem: “Why did the process of adjustment to nominal [i.e., monetary] shocks take so long in interwar economies?”

He endeavors valiantly to resolve the problem, but his efforts cannot be declared a success. He revives a theory that stemmed from the fertile brain of Irving Fisher. Under deflation, debtors may find it much harder to meet their obligations than they anticipated. Dollars under deflation increase their purchasing power, so the nominal amount of a debt becomes more burdensome. Perhaps here lies the key to the onset of depression.

A crushing objection derails Fisher’s theory. Bernanke states the point well: “Fisher’s idea was less influential in academic circles, though, because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistribution should have no significant macroeconomic effects.” Bernanke thinks he can rebut this objection through an appeal to “agency theory,” but his argument, at best highly speculative, seems to me unsuccessful. I shall spare readers the complications, but those who wish to judge for themselves should consult Bernanke’s book.

Bernanke wisely does not rely totally on Fisher. He also points out that monetary wages often failed to fall in response to deflation. This meant a rise in real wages. Does this not readily explain why unemployment persisted? Elementary economics tells us that if suppliers offer more of a good at a given price than buyers want to purchase, some of the supply will fail to be sold. If the good is labor, the case is the same: a rise in real wages will cause unemployment unless employers decide to purchase more labor at the higher price.

But if Bernanke says this, a new problem confronts him. He has not explained why prices and wages fail to adjust; he thus leaves a gaping hole in his account of the depression. He appeals at one point to Fisher’s debt-deflation hypothesis to help account for price rigidity; but his attempt seems contrived. Matters do not improve when, in a later paper, he abandons the view that rising real wages caused unemployment. “Maybe Herbert Hoover and Henry Ford were right: Higher real wages may have paid for themselves in the broader sense that their positive effect on aggregate demand compensated for their tendency to raise costs.” Now he has no explanation at all for the continued unemployment of the 1930s.

Bernanke’s problems lie deeper. Neither he nor Friedman really has a theory of the Great Depression. Rather, they have a collection of data: “Look at the correlations, “ they in effect say, “between a falling quantity of money and economic doldrums. Who can doubt that deflation causes depression?” But they have nothing better than stabs at an explanation to link the two.

This theoretical failure does not deter Bernanke from policy prescriptions, and therein lies the main danger of his monetarist account of the depression. In another speech delivered in November 2002, (a significant month for him) Bernanke said that the Fed should act aggressively to counteract deflation, though at that time he did not think it posed significant danger to the United States. If a deflation should occur, the government can always print enough money to get us out. “We conclude that, under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation.” In a deflation, consumers must get extra money; Bernanke referred in this connection to “Milton Friedman’s famous “helicopter drop” of money.”

But what makes this policy dangerous? The answer lies in another book published in 1963, Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression. In it, Rothbard developed and extended the Austrian theory of the business cycle, developed by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek, and applied it to the American example. The book has not attracted nearly the attention among mainstream economists of Friedman’s more celebrated work, although Hayek told me in 1969 that he thought Rothbard had done an excellent job. But, unlike Friedman and Bernanke, Rothbard offers more than a slew of statistics. He provides a convincing theoretical of the depression, along with radically different policy suggestions.

The Austrian account starts from a standard point; in the free market, consumers” preferences determine the goods to be produced. If people want, for instance, more “reality TV shows,” then, sad to say, they will get exactly that. People’s preferences determine much more than the particular goods that the economy will produce: they also establish the balance between consumption and capital goods industries. People face a fundamental choice: they can devote resources to make things that immediately gratify them or they can instead aim to produce capital goods that will generate a greater quantity of consumer goods in the future. Other things being equal, people prefer goods right now to goods in the future. Austrians call this phenomenon time preference, and in their view the rate of time preference determines the pure rate of interest in the economy.

“So what?” I fear many readers will be asking. However abstract this may sound, it has the utmost practical importance. Producers use the rate of interest to decide what projects to undertake. A businessman who wants to build a new steel plant, e.g., will compare the profit he thinks he can get with the rate of interest, the cost of the money he must borrow. The lower the rate of interest, the less prospective profit margin he needs to start a new project. In this way, the extent to which people value present goods over future goods controls the amount of investment in new production.

A centralized banking system with fractional reserves can derail this mechanism. If the central bank expands the money supply, this will drive the money rate of interest below the pure rate, determined by time preference. Investors, seeing the money available at a lower rate than before, will hasten to expand production. The economy will boom.

Alas, this cannot continue indefinitely. When the expansion of bank credit ceases, the rate of interest will rise. The rate of time preference has not altered, and this, once the monetary expansion has had its effect, reemerges to determine the interest rate. The fact that the money supply has increased does not change the extent to which people value present goods over future goods. When the rate of interest rises, business investments that relied on the temporarily lower interest rates no longer prove profitable. They must be liquidated; as Austrians see matters, this liquidation of malinvestments constitutes the depression.

Here precisely lies the key divergence between the Austrian theory and nearly all other accounts of the business cycle. In the Austrian view, the government should not impede liquidation of investments that wrongly relied on low monetary interest. Quite the contrary, this process satisfies the wishes of consumers. It redirects resources from capital goods industries to consumer goods, guided by the rate of time preference.

If the government acts in depression to curb deflation, as Friedman and Bernanke urge, increased bank credit will again drive the monetary rate of interest below the pure rate. New malinvestments will occur. Once more, when the expansion ends, projects will require liquidation. The attempt to avoid depression will only generate a more severe depression later.

But, you might ask, what of Friedman and Bernanke’s massive array of data that show a correlation between depression and a contraction of the monetary supply? Rothbard does not deny that deflation occurred in the Great Depression. “At the end of 1930, currency and bank deposits had been $53.6 billion; on June 30, 1931, they were slightly lower, at $52.9 billion. By the end of the year, they had fallen sharply to $48.3 billion. Over the entire year, the aggregate money supply fell from $73.2 billion to $68.2 billion. The sharp deflation occurred in the final quarter, as a result of the general blow to confidence caused by Britain going off gold.” In diametric opposition to Friedman and Bernanke, though, Rothbard contends that the Fed did not bring about this contraction though deliberate policy. The contraction instead reflected the public’s loss of confidence in the expansionary bank system. Through much of the 1920s, the Fed had followed a policy of inflation; and when the boom came to an end, the banking system received, in Booth Tarkington’s phrase, “its well-deserved comeuppance.” Those who read together Bernanke’s and Rothbard’s books will see the difference between an incompletely worked out endeavor to elicit an explanation from data and a fully developed, cogent theory.

Unfortunately, it is Friedman’s explanation, and not Rothbard’s theoretical account, that is informing public policy—and leading Ben Bernanke to believe that he can prevent another Great Depression by running the Fed’s printing press all night long.

David Gordon is a senior fellow at the Ludwig von Mises Institute and editor of its Mises Review.