April 05, 2017

Benjamin Franklin

In contrast, in Latin America, where there is a color continuum (whiter is better) rather than a color line, there are huge numbers of George Zimmerman-like people who are a little bit black. When Zimmerman shaved his head for the Trayvon Martin trial he looked oddly like the son Barack Obama never had.

In South America, transracialism is fashionable. The top Brazilian soccer star, Neymar Jr., used to look black, but by the 2014 World Cup he”d succeeded in looking like, say, a Hawaiian surfer of white, Filipino, and Puerto Rican descent who has gotten back into Blink-182.

Now, you might think that as America becomes vastly more Hispanic in numbers, American intellectual culture might start absorbing Latin concepts like the color continuum and transracialism.

But there is zero evidence of that happening, because virtually nobody who writes for The New York Times takes seriously what Hispanics think. Ms. Carroll, for example, rightly points out that in the U.S.:

You inherit race, though…. We”re reminded of this once again by Rachel Dolezal, the white woman who made national headlines in 2015 for claiming a black identity because she felt like it…. She is the biological child of white parents….

As you”ll recall, Dolezal was nationally shamed for claiming to be black at the same time the president was celebrating Bruce Jenner’s claim to be female. Dolezal’s parents had adopted blacks, so she was raised with black siblings, which might help explain her feelings. But she won almost no sympathy. Transgenderism is a recognized thing in 21st-century America, while transracialism is not (unlike in Brazil).

As Dolezal learned, in America, race isn”t, ultimately, about how you look, it’s about who your ancestors are. Carroll exults that even though her son doesn”t look black:

For my son, though, being black in America is about more than his skin color. It’s about power, confidence, culture and belonging…. That my son sees more power in centering his blackness over exploiting whatever white privilege he may ultimately be afforded is a thing of glory.

In contrast, despite all the talk about white privilege, being a generic white American is a pitiful thing:

When my son first started to black identify at about 5 or 6 years old, an acquaintance of ours asked my husband, in my presence, if he felt like we were “depriving” our son of his “white side.” My husband, a sociology professor and the author of two books on the failure of housing and school desegregation in the United States, said: “If my parents had instilled any Italian culture in me, I might want to share that with my son. But if you”re talking about general whiteness, there’s nothing there to pass down.”

At last count, 17 members of the Forbes 400 list of American billionaires had Italian surnames. Some of them no doubt identify strongly as Italian-Americans, while others see themselves as Catholic-Americans and others as just American-Americans. In any case, powerful Americans with Italian surnames aren”t insignificant, but they aren”t numerous enough to be hugely powerful, either. They aren”t seen as much of a threat to anybody.

On the other hand, if the 17 Italian-Americans joined up with the 215 to 220 other members of the Forbes 400 list of billionaires who could all lump themselves together conceptually as, say, non-Hispanic gentile white Americans, that could be a hugely powerful number, if they thought of themselves as a group.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, much intellectual effort is therefore devoted to disparaging “general whiteness” as having “nothing there to pass down.”

This divide-and-denigrate strategy appears to have been highly successful. There are no respectable organizations looking out for the welfare of the 200 million or so Americans afflicted with “general whiteness.”

Of course, a cost must be paid for this accomplishment. Thus, virtually nobody recognized the onset of the white death around 2000 until November of 2015.

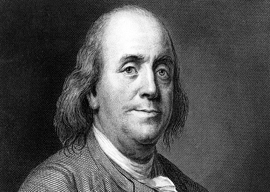

In reality, however, Europeans have recognized white Americans as the possessors of a distinctive national character at least since 1776 when Benjamin Franklin, perhaps the single most broadly successful man in history, arrived in Paris as the ambassador of the new republic.

The urbane Franklin, the most effective diplomat in American history, put on a facade for the French as a noble savage, a backwoods sage, Rousseau’s new, improved version of Voltaire. He disposed of his fashionable clothes and let his hair grow. The French went wild over Franklin’s act. He managed to talk the French monarchy into bankrupting itself to help the America republic achieve independence.

But it wasn”t wholly an act. Franklin had thought harder than anyone else about what it meant to be an American. He identified certain advantages that Americans possessed over Europeans: an absence of class strictures, a lack of peasant fatalism, and, most of all, economic freedom from the Malthusian ceiling of the Old World.

Because their population was limited while their continent was not, Franklin observed in 1754, Americans could afford to live large.

Today, Franklin’s perception of America is seen as out-of-date. The New World has been retconned by billionaires as deserving to be crowded, poorly paid, and class-ridden. Perhaps not surprisingly, each year tens of thousands of Americans brought up on Franklin’s more expansive American dream are giving up and dropping dead.