September 21, 2017

GREENVILLE, S.C.—Tobe Hooper passed away the same night Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, making it impossible for him to be properly honored in Austin or anywhere else. You could look at it as the ironic coda to a life full of bad timing, or you could look at it, as I do, as God making it rain forty days and forty nights in Texas when our most misunderstood auteur was taken.

There are four great Texas film directors—the other three are King Vidor, Richard Linklater, and Robert Rodriguez—and all except Hooper were able to acquire enough power to distance themselves from Hollywood dealmakers and make the films they wanted to make.

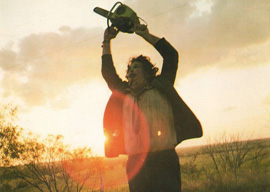

Tobe Hooper was the exception. He got beat up by the system his whole life. His masterpiece, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, was condemned as pornography by both coasts even as inferior horror films out of Andy Warhol’s Factory and Warner Brothers’ backlot were being praised as works of genius. Hooper then spent the rest of his life knocking on various Hollywood doors that would occasionally be cracked open just wide enough to give him one job at a time, often by C-level producers who turned up their noses at his pedigree and then micromanaged his work until it was all but destroyed. His one big break, Poltergeist, was plagued by the persistent fake news that Steven Spielberg ghost-directed it. This libel followed Hooper throughout his career and was even appended to many of his obituaries.

First of all, let’s state the obvious. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is one of the most successful independent films in history. (We don’t know exactly how successful because the original distribution company was owned by the Mafia.) It has been shown theatrically in almost every country in the world, and its innovations have influenced the horror genre for the past four decades. But Hooper never benefited from that reputation because, by the time the glossy high-budget remakes came out in the 21st century, Hooper’s era had passed and his reputation had never recovered from its initial association with what was considered exploitative dreck. Today he would be called a “genre genius.” Then he was just regarded as the weirdo who made a sensational grindhouse flick. People hardly remember this now, but the film was a badge of dishonor. Most of the cast members took it off their résumés, and the very title of the movie became America’s cultural shorthand for perversity, moral decline, and the corruption of children. Even 25 years after its release it remained the favorite example of congressmen calling for the censorship of television.

Yet Chain Saw is more properly understood as a sui generis art form that I’ll call Southwestern Gothic Grand Guignol Political Satire. Like all great films, it’s a dreamscape. Chain Saw was conceived, shaped, filmed, edited, and released in a kind of mild doper’s haze, like a free-love happening that, on the third day, turns a little ugly. Hooper is one of the three great hippie artists with ties to Austin—the others being Willie Nelson and Dennis Hopper—but his was the most antisocial personality of the trio. He was somewhat of a loner who could be shy and withdrawn even when he was being honored. Throughout his life he retained a latent counterculture shabbiness, with his unruly beard, mop haircut, professorial wire rims, and gravelly halting voice. (He rivaled Hopper for the number of times he used the word “man.”) But his retiring nature, sometimes bordering on the reclusive, didn’t serve him well in the Cheshire-smile world of Hollywood where he always sought acceptance.

That doesn’t diminish his brilliance. Hooper’s signature film, produced for $60,000 raised from Austin good-ole-boy politicians in 1973, was the revolutionary “angry youth” picture that Hollywood had been trying to make for several years—perhaps explaining why it was shunned by his fellow filmmakers. Besides being a horror classic, Chain Saw is a powerful antiestablishment screed at the tail end of the Vietnam era, when emotions were still raw and Nixon had just left office. Almost everyone associated with it—the notable exception being the stunning Final Girl from Houston, Marilyn Burns—had some connection to the counterculture. Hooper’s scenarist, Kim Henkel, was a lanky, drawling textbook illustrator with a droopy handlebar mustache who had starred in Hooper’s first feature, Eggshells, as a dope-smoking sexaholic poet who likes to write in the nude and discuss politics in the bathtub. Allen Danziger, who played the van driver “Jerry,” was a childhood friend of Stokely Carmichael who had traveled from the Bronx to Austin to work with the mentally retarded in one of LBJ’s Great Society programs. Dottie Pearl, the makeup artist, was a cultural anthropologist who had received government grants to make films about the Navajo. John Henry Faulk, the radio personality and humorist who was blacklisted by anti-Communist reactionaries in the ’50s and spent the rest of his life crusading for First Amendment causes while appearing on Hee Haw, contributes a cameo in the cemetery sequence. Gunnar Hansen, the Icelandic giant who played the actual chain-saw killer, was the editor of the Austin poetry journal Lucille at the time he got the part.

Yet despite the movie’s rich subtext and the precision of its Hitchcockian cutting (868 edits in a 90-minute film), it took almost three decades for it to gain anything close to critical approval. It wasn’t until the year 2000 that the British Board of Film Classification lifted its ban on the film’s distribution in England. Long considered too grisly even for late-night premium channels like Showtime and HBO, it was finally seen on television in an uncut version in 2001. Shut out from all conventional distribution networks, it still managed to find an audience. Very few horror films survive the teen generation that first sees them, yet the myths and legends surrounding Chain Saw have continuously expanded. Many people believed, and still believe, that the movie is entirely true, in part because of its effective cinema verité style.

In 1973, when the project took shape, Tobe Hooper was 30 years old and already considered the “old man” of Austin’s minuscule filmmaking community. He had seen every film released by Hollywood since 1944, frequenting all four theaters on Congress Avenue, because his father was a film buff who owned the Capitol Hotel, and the old man loved sneaking out to a movie in the afternoon, often taking his wife and infant son with him. “I think I learned cinematic language before I learned language,” he once told me. “I think I was a camera.”

At age 3 Hooper appropriated his father’s Bell & Howell 8-millimeter home movie camera and started making his own films. Throughout his childhood he used every available family member and classmate as actors, impressing his teachers by turning in class projects in celluloid form. For a seventh-grade science class he made a movie inspired by Hammer Films’ The Curse of Frankenstein, complete with the blood-emulsion tinting of the film stock, and at age 17 he completed his first “real” film, The Abyss, the story of a prisoner awaiting execution who escapes, gets killed, and goes to hell, before realizing that he never really escaped at all but has been dead the whole time. The film was shot in 16 millimeter on a budget of $700 donated by his father. “Maybe twenty people saw it,” Hooper recalled, “but when it was finished, I felt like wow! Breakthrough! Because it had sound, it had music, it was 30 minutes long. I knew I was going to be a director.”

The following year, 1962, he enrolled at the University of Texas and checked in at the brand-new film school—or, more precisely, the Radio/TV/Film Department, which had no real film equipment and only two film students. He lasted two years, never spending a day without a camera in his hand, but the most valuable contact he made was Robert Schenkkan, general manager of public TV station KLRN and, at the time, the national chairman of the Public Broadcasting System. Hooper would visit Schenkkan three or four times a week, often borrowing one of KLRN’s 16-millimeter cameras, and eventually Schenkkan gave him small jobs shooting footage for the station.

It was Schenkkan who helped Hooper land his first major directing job, introducing him to Fred Miller, an East Texas Baptist preacher who had persuaded the folk singers Peter, Paul and Mary to participate in a feature documentary. Miller hired Hooper to go on tour with them as principal shooter and director, and the resulting film, The Song Is Love, ran on every public TV station in the country for years, usually around Easter.

Meanwhile, Hooper had made his first 35-millimeter film, a ten-minute comedy short called The Heisters, financed for $7,500 by a San Francisco investor and eventual winner of an award at the San Francisco Film Festival. He had also formed a commercial production company, Film House, with four other Austin filmmakers, and during the ’60s he shot more than sixty commercials and shorts. He directed Farrah Fawcett’s first commercial (for a makeup company), filmed documentaries on the Kennedy-era Title III program to aid minorities in higher education, and made a famous short called Down Friday Street that’s credited with stopping the destruction of historic buildings in Austin.

But Hooper always lusted after mainstream Hollywood—if he could have written his own ticket, he would have made big-budget comedies—and that yearning led him on a constant search for feature funding. Unfortunately, his first attempt to impress the West Coast was a disaster. Houston investor David Ford raised $40,000 to finance a feature called Eggshells. At a time when heavy-handed youth pictures like The Strawberry Statement were attempting to “explain” the counterculture, Hooper’s idea was “to show the end of the Vietnam War, with the troops coming home, but tell it through the eyes of a commune.” Shooting with a handheld camera, aping the style of his idols Fellini and Antonioni, Hooper used real people who lived in a communal house near the University of Texas campus. Most of the script was either improvised or scribbled on napkins with his collaborator and art director, Bob Burns. Trying to flesh out a plot in a movie that had none, Hooper invented a ghostly spirit that dwelt in the basement of the house, a mysterious force that Burns eventually dubbed the “cryptoembryonic hyperelectric presence.” (It was mostly pulsating lights and spinning colors and fast-motion film—what passed for psychedelic special effects at the time. Visitors to the basement would go on a “trip” whenever they sat under an antique beauty-salon hair dryer.)