October 07, 2016

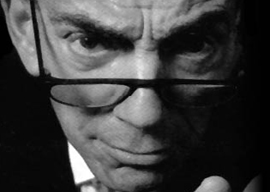

Herschell Gordon Lewis

Source: herschellgordonlewis.com

Herschell had shot two complete features in sixteen days”and three months later he was killing “em in Peoria. Since no movie of this kind had ever been seen before, it was noticed (by everyone except The New York Times). Most of the critics used words like “inept,” “crude,” “unprofessional,” and “fiasco.” “Blood Feast,” wrote Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times, “is a blot on the American film industry. In production, exhibition, and promotion it is an example of the independently made exploitation film at its very worst. It is an insult to the intelligence of all but readers of horror comic books.”

For a true exploitation genius like Herschell, there is no finer promotion than to be called “a blot on the American film industry.” He was now the king of this particular molehill. Harry Kerr, the indie theater titan of the Carolinas, played the picture in all 350 of his drive-ins. Herschell printed up “vomit bags” inscribed You May Need This When You See BLOOD FEAST, and even though half a million were passed out at screenings, they”re quite valuable collector’s items today. There were protests against the film in San Diego and Tampa, but given the subject matter, Blood Feast was remarkably noncontroversial, at least compared with the earlier furor over the nudie-cuties. Things were so slow in Sarasota that Herschell tried to stir things up by swearing out an injunction against his own film, alleging that it violated local obscenity laws. He expected to get two days” publicity out of the stunt, but the presiding judge surprised him by granting the injunction. He had to actually fight in court to get it lifted. (Sarasota had no more sense of humor 35 years later. I hosted a screening of Blood Feast at the Sarasota Film Festival, believing the city would take pride in its little slice of exploitation history, only to be cursed at as several well-heeled women made a show of walking out after the tongue-ripping scene.)

Stanford Kohlberg was so happy with the movie that he gave Friedman and Lewis money for two more gore films, both of which turned out better but neither of which became as famous. 2,000 Maniacs was a gore version of Brigadoon, about a Southern town where a Civil War massacre took place and, once every hundred years, the dead martyrs rise from their graves to take revenge on Yankee tourists. Color Me Blood Red was one of the many versions of A Bucket of Blood, the Roger Corman classic from 1959 about an artist who has to kill in order to make his works more lifelike.

But success brought conflicts among Lewis, Friedman, and Kohlberg, and after the three gore films they would never again work together. Friedman would move to Los Angeles and partner with exploitation pioneer Dan Sonney”the two of them would found the notorious Pussycat Theaters chain”while Lewis would go back to the advertising business while making films whenever he could. Neither man would have the impact alone that they had as a team.

Herschell ended up directing 38 films, using a variety of pseudonyms: Lewis H. Gordon, Sheldon Seymour, Georges Parades, Armand Parys, R.L. Smith. He would make any film for a price. He even made children’s films”The Magic Land of Mother Goose and Jimmy the Boy Wonder“as a hired gun. He made films about the sexual revolution (Miss Nymphet’s Zap-In, A Girl, a Boy & the Pill). He went through a cornpone phase with moonshine epics like This Stuff”ll Kill Ya, Moonshine Mountain, and Year of the Yahoo! (a precursor of Bob Roberts). He made the first all-female motorcycle-gang movie, She-Devils on Wheels, and one of the most brutal films about juvenile delinquency, Just for the Hell of It, as well as a little gem called Suburban Roulette about wife-swapping. One of his strangest films, on a résumé full of strangeness, is Linda and Abilene, a nude lesbian Western shot at the Spahn Movie Ranch while the Manson family was still living there!

Yet he always returned to gore”A Taste of Blood, The Gruesome Twosome“partly because he was fascinated by the magician’s challenge of creating new realistic effects that had never been seen before. If Blood Feast was the Citizen Kane of gore, then The Wizard of Gore in 1972 was Herschell’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, his final experiment in gory special effects, his swan song. That same year he moved from Chicago to Florida and got out of the exploitation business for good.

In later years, after Blood Feast became a cult legend, various writers would try to assess its place in film history by citing supposed influences on much better films made by much better filmmakers. All of this was bull. Herschell and his signature film would not be remembered at all were it not for two men who were (of course) not mentioned in the New York Times obituary. One is Jimmy Maslon, the co-owner of Hollywood Book and Poster, the fabled memorabilia shop on Hollywood Boulevard. Jimmy painstakingly searched for, located, and lovingly restored the rare prints of Herschell Gordon Lewis films that had been scattered to the four winds once Kohlberg passed away and Herschell retired. In some cases there was only one remaining print of the film, and it was usually found in the attic of someone who had bought it at a bankruptcy sale when a regional sub-distributor went out of business. The second man is Frank Henenlotter, the Greenwich Village exploitation director best known for his own cult classic, Basket Case, who brought Herschell out of obscurity in the early “80s and celebrated his films at a special festival staged at the Waverly Theater on Sixth Avenue (today known as IFC Cinema). Without Maslon the films wouldn”t exist. Without Henenlotter the man would still be unknown. Both of them collaborated on the 2010 documentary The Godfather of Gore, which is the best way to enjoy Herschell’s career without having to actually sit through Herschell’s movies. The documentary was mentioned by The New York Times, but without credit to either Maslon or Henenlotter.

What would have amused Herschell most about the Times obit is that it made claims he never would have made for himself. “Blood Feast is an accident of history,” he once said. “We didn”t deliberately set out to establish a new genre of motion picture. Rather, we were escaping from an old one. Blood Feast is like a Walt Whitman poem. It’s no good, but it’s the first of its type.”

And that’s what I loved about Herschell. No matter how many bad movies he made, and no matter how many people told him they were good movies, and no matter how much he would have liked to have been a real director, he couldn”t kill the old English professor who knew better. Screw the Times obit. Herschell would rather know that somewhere, somehow, in commemorating his death, a theater owner saw box office numbers you would not believe.