July 19, 2018

Source: Bigstock

DALLAS—I started getting panicked messages around 8:30 Friday night.

“Joe Bob, I can’t get in. I think my computer is fried.”

“Joe Bob, WHAT THE HELL.”

Emails, texts, instant messages, tweets.

“Joe Bob, something is wrong with your show.”

“Joe Bob, I have forty people in my basement, we’re breaking out the Lone Stars and we can’t get a signal.”

Anger. Befuddlement. Apologies.

“I know I promised to watch your show, but apparently my lame wi-fi connection . . .”

And then, as if some psychic force penetrated the ether and entered everyone’s brain at the same time . . .

“OMG.”

“OMG.”

“OMG.”

I think I may have set the record for OMG’s received in a five-minute period.

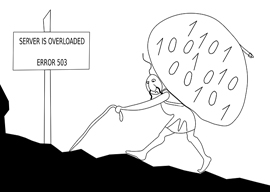

“Joe Bob, you overwhelmed the servers! You broke the Internet!”

This was, I was assured, a good thing. This suddenly turned all the anger and befuddlement to unalloyed joy.

Word spread so fast that it quickly became a “trending topic” on Twitter. Over the next 24 hours there were three related hashtags that popped in and out of the top ten trends, right alongside #WorldCup, #TrumpinScotland and #ThaiCaveRescue. At one point those trends included the hashtag #BloodFeast, a reference to one of the movies I was hosting—the 1963 gore film about a maniac Egyptian caterer named Fuad Ramses—which must have been unsettling to unsuspecting surfers throughout the Twitterverse. Since I was determined to be available for real-time blogging, tweeting and posting, I stayed up 36 hours dealing with the more dedicated horror fans as they tried to view as much of the show as possible by switching among various devices, using unauthorized Twitch feeds, and, in some cases, viewing grainy videotaped captures off a working laptop screen being rebroadcast to other fans around the country.

Then, just when it seemed like everything had stabilized—around Hour 18 of the 24-hour horror-movie marathon—the servers crashed a second time as too many people tried to tune in for the finale on Saturday night. “Engineers working through the night”—our assurance from the tireless team sent by the Shudder streaming service to fix it—turned out to be insufficient to accommodate the now enlarged audience, attracted by the “What the hell is going on?” factor.

The upshot of all this chaos was a chorus of well-meaning fans emailing me in the aftermath to say, “You should be proud and happy.”

Uh . . . no.

You don’t write, perform, shoot, edit and broadcast a 24-hour show and then feel good about nobody being able to see it. You start out with a fear of disappointing the audience—I have the greatest fans in the universe, and I love them, and they’ve saved my ass a thousand times, and so preventing them from seeing the opening title card is sort of my ultimate nightmare.

“But, Joe Bob, people will eventually see it, the important thing is that you broke the Internet.”

If that’s the important thing, it shouldn’t be the important thing. Not everyone can hang around for two days monitoring their devices. The casually interested observer, who might have been barely intrigued enough to sample the show, was gone after 15 minutes and never came back. “Breaking the Internet” is not a happy thing for those of us who believe communication is better than gossip.

So let’s break this down. I have three big questions about the concept of breaking the Internet.

Numero Uno: Wasn’t the Internet invented by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Pentagon’s secret lab? And don’t we know from Edward Snowden that when it was released to the public in the early 1990s, the National Security Agency put so many “back doors” in it that it can be manipulated in nine million different ways to do whatever the United States wants it to do? How, then, can it be so fragile, especially when used by American companies utilizing American servers?

In other words, how can it be, on the one hand, the scariest spying system ever invented and, on the other hand, a halting, flickering, unsteady Model T that breaks down every five minutes even when you have “engineers working through the night.” (Many people reported periods of connectivity that would last, say, 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of black screen, followed by 20 more minutes of connectivity, throughout the two days.)

Numero Two-o: Why do people celebrate when the Internet goes down?

I think the answer to the second question is related to the first. The Internet “breaking” is a victory over Big Brother. The powerlessness of “servers”—do they call them that to be ironic? shouldn’t they call them “overlords”?—makes people feel, for a few hours, like the masters of the universe are clueless and lost.