May 30, 2018

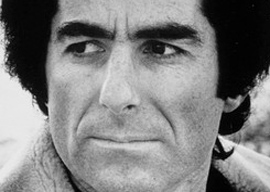

Philip Roth

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The deaths this month of literary giants Tom Wolfe, age 88, and Philip Roth, 85, illuminated a little-noticed divide in American life. The two writers were fairly comparable combinations of talent, energy, ambition, and personality, so it’s instructive to see how their reputations differed.

Roth’s passing revived a debate among Jewish critics that has been sputtering along since he published his 1959 satire on the Jewish American Princess, Goodbye, Columbus: Is Philip Roth good for the Jews or bad for the Jews?

Should his many strong novels entitle Roth to be admired by other Jews as a Jewish hero? Or were his books, especially his funny but vulgar 1969 best-seller Portnoy’s Complaint, about a shiksa-chasing liberal lawyer’s Jewish guilt, excessively frank about Jewish life?

In Portnoy’s Complaint, Jewish guilt is the diametrical opposite of white guilt: Portnoy feels guilty not because his ancestors were too ethnocentric (as in white guilt) but because he’s not ethnocentric enough to satisfy his ancestors, who want him to knock it off with the gentile broads, settle down with a nice Jewish girl, and propagate the race.

To Roth’s Jewish critics, his insufficient feelings of Jewish guilt revealed him to be a self-hating Jew. That might seem convoluted, even contradictory, but the point was never to make the rules lucid to the American public, but to discourage Roth from using his skills to let his gentile readers in on how things worked.

But if the early Roth was seen as too honest to be good for the Jews, did Roth’s anti-gentilic 2004 alternative-history novel The Plot Against America, in which the election of Charles Lindbergh as president in 1940 is bad for the Jews, make up for his youthful indiscretions?

As Americans, we are all used to Jews arguing over whether or not various things are good for the Jews. Some Americans may find these displays of ethnocentrism unseemly, but if you are not Jewish, you’d be well advised not to mention that view in public. One thing Jews can agree upon is that gentiles having an opinion on Jews is not good for the Jews.

On the other hand, virtually nobody ever argued over whether Tom Wolfe was good for whichever ethnic group he was assumed to represent.

Was Tom Wolfe good for the Southerners?

But nobody ever asks whether a white gentile is good for the white gentiles.

And did many even notice Wolfe was Southern?

Even though Wolfe, who wore a trademark white suit in the attention-calling tradition of Mark Twain, was one of the more famous American writers ever (eventually surpassing in celebrity, for example, interwar North Carolina novelist Thomas Wolfe), he almost never was seen as representative of any ethnicity, region, or political stance. (If anything, he was initially seen as a Sixties Person due to his book about Ken Kesey’s LSD cult, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.)

There’s much to be said for being treated as a sui generis individual. On the other hand, it should have always been rather obvious that Wolfe was a Southern WASP conservative. And yet that was almost never disclosed about Wolfe.

This was not for a lack of publicity. The New Journalism of the 1960s, in which reporters like Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson wrote like novelists while novelists like Truman Capote and Norman Mailer researched like reporters, was both prestigious and popular. It was fun.

Not surprisingly, the New Journalists did not suffer from a lack of coverage by other journalists. As the most dazzling, broadest-ranging (from Radical Chic to The Right Stuff), and most enduring New Journalist, Wolfe never lacked for newsworthiness.

In his early 40s, Wolfe began to trash-talk the reigning literary novelists of the early 1970s about how a real reporter could write a much better novel than them in the time-tested Trollope tradition of The Way We Live Now.

Fiction proved much harder to write than Wolfe had expected, however, but finally fifteen years later he delivered his first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities. It’s not the Great American Novel, but it’s definitely the Great New York City Novel, the most foresightful analysis of Current Year America penned during the 20th century.

Critics were somewhat baffled about what to make of this impolitic novel about our society’s Hunt for the Great White Defendant. But reality almost immediately vindicated Wolfe’s perception of the future of race relations when Al Sharpton (Reverend Bacon in Bonfire) began promoting Tawana Brawley’s claim of being gang-raped by white police officers in what turned out to be the first modern Hate Hoax.

Wolfe’s cultural prestige was so high as the literary embodiment of the ’60s that he could hardly be ruined for his political incorrectness without raising uncomfortable questions for the literary gatekeepers about their failure to notice what Wolfe had long been up to.

Paradoxically, Wolfe was made distinctive by his lack of white guilt and Roth by his lack of Jewish guilt.

Rather than pad his observations of African-American culture with boring boilerplate blaming whites, Wolfe simply didn’t bother doing what everybody else was doing.

Conversely, Roth did the unusual in satirizing Jews (as, to a lesser extent, did Wolfe, who showed courage in not letting his WASPness get in the way of good laughs at Leonard Bernstein’s expense in Radical Chic).

Strikingly, it seldom seemed to occur to observers that Wolfe, with his lack of white guilt, was a product of a particular time and place.

In truth, he grew up in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, and his father edited Southern Planter magazine. Wolfe took pride that his forefathers had fought for the South.

Finally, an octogenarian Wolfe authorized his protégé Michael Lewis, a New Orleans WASP, to read his letters to his parents. Lewis pointed out in 2015 that up through Wolfe graduating from Washington and Lee College in Virginia,

there isn’t a trace of institutional rebellion in him. He pitches for the baseball team, pleases his teachers, has an ordinary, not artistic, group of pals, and is devoted to his mother and father.