March 29, 2017

Dark Side of the Moon, Pink Floyd

Nobel-winning economist Angus Deaton and his wife, Anne Case, have released a new study, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” enumerating how many unprivileged whites have died from despair while privileged whites prattled about the curse of white privilege.

Judging from mortality statistics, something very bad has happened to working-class white Americans in this century.

The downturn in life expectancy has occurred despite continued advances in medical technology that are steadily boosting life spans in other countries. In 2015, life expectancy fell for Americans overall, stemming in part to a sudden spike in black male death rates, perhaps due to the Ferguson Effect of blacks shooting blacks in increasing numbers following the rise of Black Lives Matter in 2014.

But mostly the decline was caused by continued increases in death rates for young and middle-aged whites. The White Death hasn”t gotten as bad yet as the horrifying drop in Russian male life expectancies during the Yeltsin years. Yet it’s reminiscent of the tendency of Russians to react to the slow moral decay of Communism and to the sharp shock of defeat in the Cold War by drinking themselves to death.

Nonetheless, until just 18 months ago, barely anybody in positions of authority or influence in America had noticed it, so pervasive is our system’s animosity toward whites of humble backgrounds. (Matt Stoller here lists homicidal comments about working-class whites left on the Huffington Post.)

In fact, it’s possible that the only reason the White Death is talked about today is a coincidence in the fall of 2015.

On Oct. 12, 2015, Angus Deaton of Princeton was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. Granted, economics isn”t a real Nobel, but it’s treated as one. So Deaton’s name was still in the news three weeks later when he and his wife, Anne Case, released a paper on how death rates among middle-aged whites had been rising since the end of the 1990s.

Deaton and Case had previously had their paper rejected by two prestigious medical journals.

The big killers driving this increase have been what Deaton and Case now call “deaths of despair”: overdoses of prescription painkillers and heroin, alcoholic liver disease, and suicide.

Veteran science reporter Gina Kolata reported in The New York Times in 2015 on how surprising this was:

David M. Cutler, a Harvard health care economist, said that although it was known that people were dying from causes like opioid addiction, the thought was that those deaths were just blips in the health care statistics and that over all everyone’s health was improving. The new paper, he said, “shows those blips are more like incoming missiles.”

Why the obliviousness?

For one reason, there are virtually no respectable organizations that make it their mission to care about the well-being of whites. Countless government agencies and NGOs scan statistics for evidence that blacks are getting a bad break. But looking out for whites is a good way to wind up on the SPLC’s list of people to hate, so nobody paid much attention to life-and-death trends among 200 million people.

Fortunately Angus Deaton, Nobel Laureate, demanded attention.

After that, a lot of people dug into the numbers, with some of the better work done by college student Jason Bayz.

It quickly emerged that the White Death was focused among whites without college degrees.

To some extent, this is a statistical artifact as college graduation rates have drifted upward for each successive age cohort: Therefore, a 55-year-old in 2015 is more likely to be a college graduate than a 55-year-old in 1999, so non”college graduates today are somewhat more likely to be concentrated among people with problems.

But on the whole, it’s very much a real problem.

A postelection study by The Economist last November found that the only measure that better predicted a swing from Romney to Trump at the county level than percentage of noncollege whites was a composite measure of public health. Trump swing voters tended to see it as their civic duty to elect somebody who would at least promise to do something to stop the trend in their neighborhoods toward disease and death.

Deaton and Case summarized their latest thinking at the Brookings Institution last week.

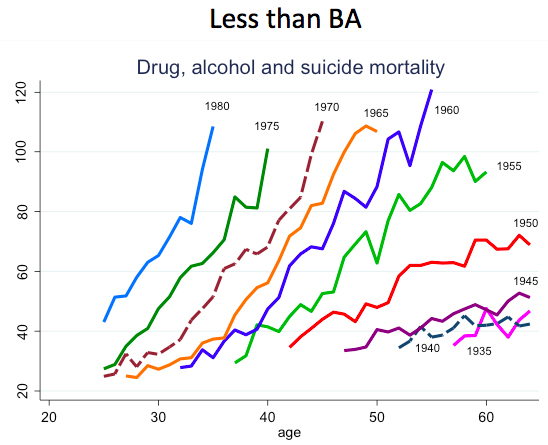

Below is their graph showing the growth of deaths of despair for non-Hispanic white working-class cohorts born five years apart.

The mortality patterns for those born in 1935, 1940, and 1945 were all similar, but the drift toward early death from drugs, alcohol, and suicide began with those born in 1950, and greatly accelerated among those born in 1955.

I find it useful to mentally add 18 years to birth dates to understand when a cohort reached the beginning of adulthood.

Thus, the children born in 1945 (mauve line) turned 18 in 1963. Hit songs in 1963 included “Surfin” USA” by the Beach Boys and “Walk Like a Man” by the Four Seasons. The most drug-oriented hit was “Puff, the Magic Dragon” by Peter, Paul, and Mary.

In baby-boomer mythology, 1963 is the last prelapsarian year before the generational loss of innocence that was the JFK assassination that November. By the time the Beatles landed at JFK in February 1964, the world had changed. This oft-told tale doesn”t sound plausible, but we keep stumbling upon evidence for it, such as this graph.

In contrast, those born in 1950 (red line) were 18 in 1968. The biggest hit of the year was “Hey Jude” by the Beatles. The Beach Boys didn”t have a major single that year because Brian Wilson was an acid casualty at age 25.

Those born in 1955 were 18 in 1973, perhaps the nadir of the “70s. The biggest-selling album released that year turned out to be Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

Deaton and Case offer an economics-centered view of what went wrong.

Tentative story: slow collapse of white working class

“Each birth cohort entering the labor market without a BA after those born in 1945

“Men start with lower real wages

“Have worse subsequent careers, lower returns to experience

Those lucky enough to be born in 1945, the year before the baby boom began, went through life with supply and demand tilted in their favor. Relatively few babies were born from 1930 to 1945, so the labor of young men born in 1945 was well compensated when they reached 18 in 1963.