September 07, 2019

Salvador Dali

Romy Somerset is the sweetest, nicest young girl in London. She’s also my goddaughter, and I remember during her christening at Badminton years ago the present duke’s mother staring at me rather intensely while the minister was going on about love, trust, and faithfulness. At lunch afterwards I asked Caroline Beaufort why the looks. “I was wondering if you recognized any of those words,” said a laughing duchess.

Well, I do now that I’ve become monogamous by “force majeure,” but that’s not the point of my story. I am quite annoyed with Romy because she sent me a book that I have been unable to put down, one that has actually interfered with my pursuit of the high life. Romy works for Quartet Books, Naim Attallah’s publishing gem, which has employed more pretty girls than MGM and 20th Century put together. The book that Romy sent me is Brian Sewell’s The Complete Outsider, both volumes already best-sellers seven years ago, but this time reissued in a single volume. I never met Sewell while he was alive and writing about art and people, but I was aware of how waspish and masterful of the devastating retort he could be when he came across something false or pretentious. Although he was 100 percent homo, and I am 100 percent hetero, I found his outspokenness to be not only very courageous, but the essence of truth. In reading the opus, Sewell’s emotional honesty breaks through time and again.

Here’s a passage about old age that had me shouting out loud, “How true, how f—ing true”: “Yet old men lust after the young, not once a week or once a day or hourly, but in response to almost constant stimulus. It is the young skin that does it; the conventions of beauty are a bonus. But when the skin of the young is flawless, it is what most makes the fingers reach, as though aching to caress.” Recently, while talking to some young whippersnappers in Greece, I said something to that effect but much more crudely: Don’t believe any of that crap about wisdom and contentment in old age. You’re just as horny as ever, but a bit choosier, that’s all. Sewell says it better: “Inside his own skin, rough and wrinkled, pallid with approaching death, the old man feels the same sensual sensations as the young, but he may not touch.” Ouch!

An eerie business is the one about death and making a will. One becomes a judge and jury of one’s friends, dispassionate and coldly rational, “reward and revenge standing at his elbow ready to nudge his pen.” Not in my case. I’ve already made a will long ago and turned everything over to the mother of my children. Let her deal with it, I simply cannot face it. When I signed the will in front of a lawyer and notary public, the lawyer asked time and again if I was in my right mind. (It’s a Swiss requirement.) “Not really,” I answered, “but she’s got a gun pointed at me under the table.” The Swiss did not find it funny and demanded I get serious. “I’m seriously out of my mind,” I repeated, “but I don’t wish to be shot in cold blood.” They threatened to walk out, so I gave in and signed after categorically stating that I was turning all my assets over on my free will. I could almost hear them thinking what an idiot I must be. The Swiss do not believe in letting easily go the root of all envy.

A will precedes death, and Sewell is brilliant in detailing the “crumbling memory, the trembling hand of the octogenarian unsteady with the fork, unsteadier still with the lavatory paper.” Hang on, Brian, it’s not that bad yet, I can still go full-out in judo and karate, and I only tremble when I think of the will I made. (And when a beautiful girl crosses my path.) Sewell is great where the mind toward the end is concerned: “No opera, no Schubert songs, no violin concertos, no theatre, no galleries, no books.” I add no more competitions, no more seductions, no more three-day and -night benders.

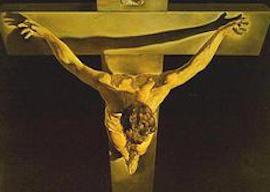

Sewell is right about Dalí, whom he met in the ’60s, just about when Salvador sold his wonderful Jesus-on-the-cross painting to my father, a painting he comments on. He’s also good about Andy Warhol, another acquaintance of mine, and he gets him spot-on: “Andy made very little sense at night. He was not much more sensible by day, in fact he was largely inarticulate.”

He describes homosexual encounters when still against the law like a commando during an operation in the menace of darkness until one’s vision kicks in, and conveys how much hearing is heightened under such pressures and circumstances. He also is aware, when by the Thames, of the “danger of the sudden presence of the river police patrolling in a boat with the engine shut down and all lights off, the fierce beam of its searchlight suddenly cutting through the night.” You’ve come a long way, says I—now we need a searchlight to find straight men, and soon the fuzz will be after us at night. Ironically, I read the memoir along with that of Ernst Jünger, the decorated German officer who was awarded the Blue Max in WWI. Jünger was also a writer extraordinaire and a religious man, and spent WWII in Paris. His thoughts on death and life are far more mystical and deeper, but then he was a German officer of the old school.