March 01, 2024

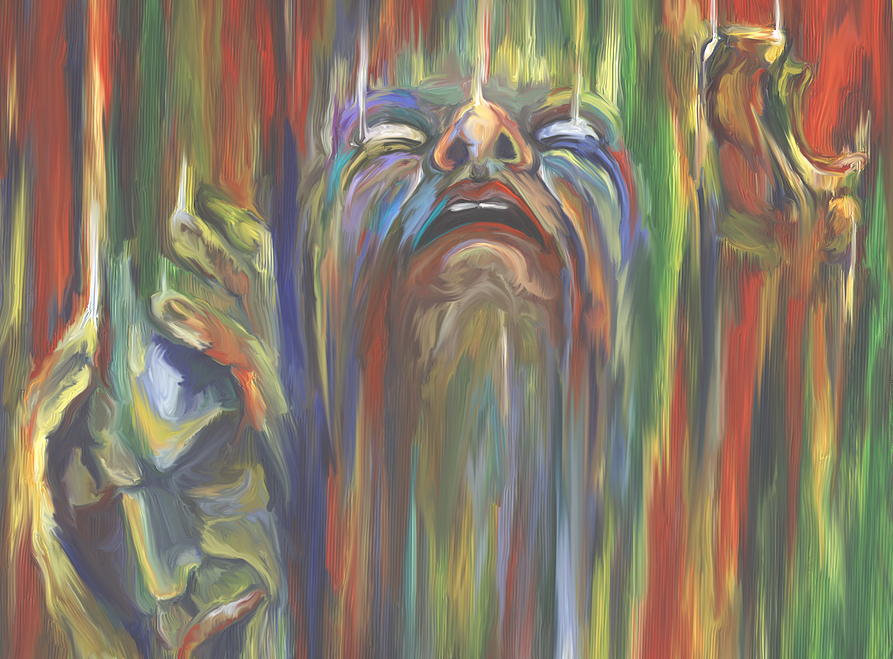

Source: Bigstock

On the whole, the cinematic world has dealt less severely with Communism than it has dealt with Nazism. The reason for this is at least twofold.

The first is that many in the cinematic world were sympathetic to Communism, at least in the abstract—which is to say, they might want it for others, though not themselves. Equality was for them what the abandonment of sin was for St. Augustine: They desired it, but not just yet. And when it was no longer possible to deny the horrors of Communist regimes, they probably did not want to display to the world the truth of what they had so long sympathized with. Their sympathy for it was now an embarrassment, as it remains even for their intellectual successors.

The second reason is that economic egalitarianism is a more respectable doctrine than racism, even if, in its extreme form (Communism), it has, overall, been as responsible for as many deaths. Few indeed must be the people who have never wondered whether the extreme wealth of a few individuals is good or healthy for society as a whole, even if they are unable to specify exactly what degree of economic inequality in a society is permissible or desirable. This is a question into which I do not here want to go.

Actually, the crimes and cruelties of Communism were known from the very beginning. Over the years, I have collected books published from the date of the Bolshevik coup—often mistakenly referred to as a revolution—to the outbreak of the Second World War. Everything was reported from the first: It required no Solzhenitsyn, magisterial as his work was, to reveal it. The problem was that the evidence was not believed, being widely and successfully attributed to malevolent political prejudice. One problem that threw dust in the eyes of the public was that there were many books of opposite tendency that sang the praises of the Soviet regime, with titles such as The Soviet Union Fights Neurosis and The Soviet Union Fights Crime (successfully, of course). Moreover, the world was in so terrible a condition that people wanted to believe in political miracles.

Recently I went to see a new Romanian film called The Pitesti Experiment. Rather unusually, it dealt uncompromisingly with the brutalities practiced by a Communist regime, in this case the newly established one in Romania after the Communists achieved total power.

Romania was, alas, no stranger to brutality. When the Romanians occupied Transnistria and Odessa, even the Germans were astonished at their brutality. Unusually, the Romanian intelligentsia before the war was sympathetic to, or actually complicit with, the Romanian fascist movement. The famous writer Emil Cioran, who emigrated to France and subsequently wrote in French, spent the rest of his life repenting (or at least covering the traces of) his previous commitment to Romanian fascism, doing so by promoting a philosophy of disabused world-weariness and refusal of commitment to anything. When he said that the prospect of having a biography written about him should be enough to discourage anyone from trying to achieve prominence, he knew whereof he spoke.

The Pitesti Experiment is a no-holds-barred depiction of the methods used to “reeducate” supposed enemies of the new regime by means of humiliation and severe torture, turning them in turn into torturers themselves of other supposed enemies. These methods were a kind of extreme criminal perversion of the early-19th-century Lancastrian system, according to which older pupils taught younger pupils.

The efforts made in totalitarian regimes to procure bogus confessions have always mystified me a little. Why not just shoot or otherwise kill the supposed enemies of the regime, if that is what you want to do? Why bother to obtain confessions first when you have total power already, especially when the confessions are both intrinsically unbelievable and obviously obtained by force?

Presumably they were for propaganda purposes, if one remembers that the purpose of propaganda in Communist states was not to inform or persuade, but to humiliate: that is to say, to force people to pretend to believe what they could not possibly believe, and to celebrate what they most detested, including their own enslavement. Of course, the confessions also broke the spirit of those who made them, even if they survived. How could one respect oneself when one had given in to obvious lies in order to put an end to torture? What the regime wanted (though perhaps its leaders never quite put it this way) was a population that hated and despised itself.

The film graphically represents the torture, or tortures, employed in Pitesti prison between 1949 and 1951. It does not invent anything: There is documentary evidence for all that is portrayed. My wife had to look away, or cover her face with her scarf, so horrific was what was depicted; and I felt a confusion of sentiments as I watched.

Was my own inclination to look away mere cowardice or false sensibility, mere refusal to confront reality? Or was it shame that I was sitting comfortably in a cinema, having had a good meal, watching such things almost voyeuristically? (The people next to me, Romanians, were eating popcorn, which I find pretty unpleasant at the best of times, which this was not.)

Should artistic considerations limit the literal representation of real historical horrors? It has long been a belief of mine that the implicit works more powerfully on the mind than the explicit, the unsaid than the said: But is this true? There were scenes in this film whose verisimilitude I did not doubt, but against whose length and repetition I rebelled mentally. Repetition, Napoleon once said, is the only rhetorical device or method that works, and in this film is used to drive home the message that the extreme torture was not a momentary aberration, a rush of blood to someone’s head, but a system blessed and even demanded, at least for some years, by the ruling power. Artistically, however, I felt the dwelling on the torture was a mistake; though whether artistic considerations count in the context, I am unsure.

The principal torturer started life as a decent young man; but, under the threat of torture himself, became the worst of the worst—until the regime, ever willing to betray its own, turned on him and had him executed. Is the lesson that, under the right conditions, we can all become the worst of the worst?

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Ramses: A Memoir, published by New English Review.