March 08, 2013

Bob Mathias

I recently addressed The Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society for the Kilburn Lecture on “The Future of the Olympic Games.” Instituted in 1781, the learned society is Britain’s second oldest after the Royal Society. John Dalton, the father of modern chemistry, was one of its important past members. My NBF Peter Barnes (I had to explain to him the acronym meant New Best Friend) picked me up at the airport and whisked me to the Manchester Metropolitan University and in 45 minutes I had changed into evening clothes and was facing a jolly audience of bearded professors, smiling ladies, and an all-around appreciative audience that laughed at my jokes and was extremely generous with their applause. I spoke for 45 minutes and had an intelligent question-and-answer period of 15 minutes. One gentleman asked me why Lindsay Lohan hadn’t come with me, and I told him that, alas, she was most likely in jail and thus incapable of travel.

A lively dinner followed and the wine flowed, as did the vodka later in the university’s bar. A 45-minute speech is quite long, and although I had six months to prepare it, I had only begun to write it down three days previously. But I knew my subject by heart and after a few fervent prayers, I was pretty certain I’d somehow wing it. What also helped were two double whiskeys just before going on the podium. One more double would have meant disaster with a capital D; a single double would have meant close but no cigar. But as I said, the society’s members were very friendly, many of them are Spectator readers, and one gentleman even knew about my ships and those of my father.

I began with a short history of the Games that first took place in 776 BC. I mentioned Arrachion, the famous pankration athlete who won his third medal posthumously because just as he expired he broke the toe of his opponent, who surrendered. Nero tarnished the Games in 67 AD by disqualifying all entrants and winning the chariot race unopposed. By 339 AD, the Games were abolished because they had become too corrupt.

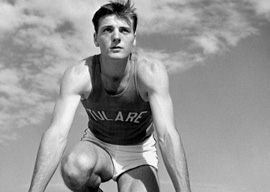

I then ran through my favorite moments of the modern Olympics: Bob Mathias winning the decathlon in 1948 as a 17-year-old Californian of Greek extraction, and with his Apollo-like looks repeating four years later; Emil Zátopek’s 1952 triple victory in the 5,000, the 10,000, and the marathon; the German Armin Hary winning the 100 meters in Rome in 1960; my friend Tony Madigan beating Cassius Clay—AKA Muhammad Ali—in the boxing semifinals in Rome and being robbed by the judges; and the barefoot Ethiopian sergeant Abebe Bikila smiling his way through the Villa Borghese gardens and down the Via Veneto while receiving the greatest cheers from the Roman crowd.