February 14, 2018

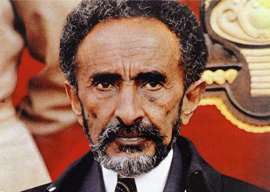

Haile Selassie

Source: WIkimedia Commons

In our disillusioning modern world, where it’s too easy to look up what life is actually like in the remote real places that used to serve our desire for utopias, Americans now apparently feel the need to believe in CGI movie fictions, such as Wakanda, a technologically advanced isolationist kingdom in northeastern Africa featured in the upcoming Marvel comic-book blockbuster Black Panther.

Wakanda, as you may have heard, is vibrant due to its massive deposits of vibranium, a literal Magic Dirt, which proves Trump is racist. Or something.

Nobody can quite explain the logic of Wakanda Worship, but it’s extremely popular at the moment.

In the old days, however, it was easier to fantasize about distant lands that were at least nominally existent.

The American media, for example, periodically became infatuated with the purported sweetness of life under some far-off Communist regime. For example, virtually no Americans visited Red China from 1949 to 1971. But over the next half dozen years, the handful of Western celebrities allowed into Mao’s dismal post–Cultural Revolution China, such as economist John Kenneth Galbraith and actress Shirley MacLaine, tended to come back exulting that Red China was, when you stopped and thought about it, better than America (which had just landed a man upon the moon).

None of this made much sense, but the admirableness of Mao’s China was conventional wisdom among American intellectuals from New York Times columnist James Reston’s 1971 trip with Henry Kissinger, during which Reston had his appendix removed using only acupuncture as anesthesia, until art historian Simon Leys’ debunking book Chinese Shadows in 1977.

Similarly, forty years earlier, a host of Western intellectuals, newly converted to Marxism by the 1929 stock market crash, had made enraptured pilgrimages to Moscow to be bedazzled by Stalin’s murderous Soviet Union.

Far more forgivable was the outside world’s long love affair with the hope of a Wakanda-like lost kingdom in the highlands of Eastern Africa. For example, H. Rider Haggard’s 1885 King Solomon’s Mines about a well-governed Zulu kingdom in East Africa was one of the most influential adventure tales of all time.

(In contrast, lowland West Africa attracted less romantic speculation. In the tropics, heat, humidity, and fever swamps are less appealing than temperate altitude.)

Indeed, there really was a relatively isolated literate civilization in the mountains of northeast Africa: Ethiopia (or, as it was often known, Abyssinia).

Ethiopia is at a pleasant altitude. The current capital, Addis Ababa, is at 7,700 feet elevation. It’s average high temperature ranges from 69 degrees during the July rainy season to merely 77 in March.

While most of hot sub-Saharan Africa was beset by infectious diseases that kept the population low and widely dispersed, Ethiopia’s climate allowed more intensive settlement, more like a Middle Eastern land. It attracted Arab settlers from climatically similar Yemen across the Red Sea. Ethiopia had an ancient written Semitic language and impressive churches hewn from solid rock. In 1896, Emperor Menelik II defeated the invading Italians, the only long-term defeat Africans imposed on Europeans in a test of arms in the 19th century.

But that also means that Ethiopia has often been closer to its Malthusian population ceiling than most of the rest of Africa.

The rise of Islam in the seventh century had cut Ethiopia off from the rest of Christendom. Edward Gibbon wrote in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

Encompassed by the enemies of their religion, the Aethiopians slept for near a thousand years, forgetful of the world by whom they were forgotten.

Interestingly, it appears that Christian Ethiopia may have first reached out to medieval Europe rather than vice versa. Perhaps due to word of the ongoing success of the Christian reconquista of Spain, in 1306 the Ethiopian emperor sent a diplomatic delegation of thirty to the Pope in Avignon to discuss a mutual defense pact against the Muslims.

Roman Catholics had long dreamt of contacting a Christian ally on the far side of the Islamic world, perhaps in India or Central Asia, to open a second front against the Muslims. They had a name for this legendary potential comrade: Prester John. He was believed to rule a kingdom filled with exotic wonders, but still friendly to Western Christians.

The arrival of the Ethiopian delegation helped convince Europeans that Ethiopia instead must be the home of the formidable Prester John.

This proved confusing to Ethiopian diplomats, such as the four who attended the Pope’s Council of Florence in 1441. They patiently explained that “Prester John” was not one of the many titles of their king. But Westerners paid their protests no mind since their strategy was the same as Prester John’s would be: to team up with Europe against Islam.

After Portuguese navigators rounded the Cape of Good Hope and reached the Indian Ocean at the end of the 15th century, a Portuguese-Ethiopian alliance became tangible. In 1543 a Portuguese expeditionary force teamed up with troops of the Emperor Gelawdewos to defeat a Muslim invasion from Somalia.

In 1622, Iberian Jesuits converted the progressive emperor Susenyos I from Monophysite Christianity to Roman Catholicism, causing him to renounce all but one of his wives. This led to civil war within Ethiopia, and the emperor gave up his quest in 1632, sending the Jesuits home.

Since then, other countries have attempted to use Ethiopia as their own Prester John. Japan, for example, went through an Ethiopia craze after Haile Selassie’s coronation in 1930, admiring the Ethiopians as another nonwhite nation with an emperor. But the Japanese government prudently refused to come to Ethiopia’s defense when it was attacked by Mussolini’s Italy.