September 23, 2017

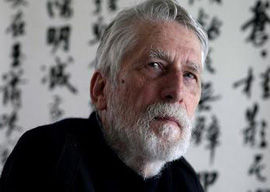

Pierre Ryckmans aka Simon Leys.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

When I was asked to name the contemporary writer whom I most admired, I used without hesitation to say—until he died in 2014—Pierre Ryckmans, better known as Simon Leys.

Leys was a Belgian who lived more than half his life in Australia. He was a Sinologist, art historian, novelist, literary essayist, and translator: from Chinese into French and English, French into English, and English into French. He was a gifted artist (and his Chinese calligraphy was admired by Chinese connoisseurs of the art, which is high praise indeed); he was also an intrepid sailor and navigator.

He first came to fame (outside the restricted circles of Western Sinology) with a series of four books about the so-called Cultural Revolution in China and the dim-witted veneration in which Mao Tse-tung was held by a considerable proportion of the European and American intelligentsia, particularly the French. I remember reading these books when they first came out; their style was so brilliant, the author’s wit so excoriating, and the subject so important that they are still in print today, more than forty years later, and are of such literary merit (unlike the vast majority of books about current affairs) that I think they will still be worth reading, and be read, a hundred years hence.

All his subsequent books were just as brilliant; if there was a finer literary essayist in the world than he, I did not know of him. Somehow he conveyed his absolute authority—both moral and literary—from the very first sentence of anything that he wrote. He never descended into obscurity and could say the most serious things with a light touch and in the simplest language.

He is now the subject of an excellent biography by a fellow Belgian Sinologist, Philippe Paquet, who admired him greatly; but only, I think, because he was in the highest degree admirable. Leys’ personal life was a very happy one, and there is no scandal to recount. The biography (which is long) is mainly, and rightly, an intellectual and spiritual one.

There is one episode in the book recounted in detail, of which I knew only the outline before, that struck me deeply. It does not reflect badly on Leys, far from that; but it left me with a feeling of deep melancholy.

Leys, who was a man as remote from self-advertisement or self-promotion as possible, was in 1983 invited onto a French television program about literature called Apostrophes. It had a very large audience for such a program, about 3,000,000 viewers. Also to appear on it was an Italian woman, Maria-Antonietta Macchiocchi, who had been an ardent Maoist and who, after a visit to China during the Cultural Revolution, had published a book titled De la Chine, about China, which was full of the most gushing sentiment about that terrible episode. Because of the ideology that she espoused, she was utterly credulous and foolish. She believed she was witnessing a dream come true when she was in the midst of a nightmare involving scores of millions of people and the total destruction of much that was precious. In terms of deaths, it wasn’t as bad as the Great Leap Forward ten years before the Cultural Revolution was unleashed, but it was bad enough.

Leys was outraged by people like Macchiocchi because he loved both the people and civilization of China. He regarded her and her ilk as utterly frivolous and ignorant, fundamentally uninterested in that of which they wrote, and using China as merely a convenient tool in the resolution of their trivial personal psychodramas.

Macchiocchi was born in 1922, into an anti-fascist bourgeois Italian family. In 1942, she joined the Italian Communist Party and later became a journalist in its service, being among other things a correspondent in Algiers during the war there. She broke with the party to become a Maoist after the Chinese-Soviet rift. She wrote her book after a visit to China, not speaking a word of Chinese and led by the nose by her official guides.

Leys had already criticized her severely in print, but she appeared to have forgotten that. She was asked to speak first:

I need hardly say that my life has been very chaste, one of pure devotion. The saints marry God, I married the people, and occupied myself with their redemption. I immolated myself day and night.