June 06, 2012

To anybody who saw Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey as a child, Pythagoras’s 2,500-year-old intuition that astronomy and music must be intertwined seems self-evident. The opening minute of 2001 is set to the thunderous “Sunrise” sequence of Also sprach Zarathustra, Richard Strauss’s Nietzschean tone poem of 1896.

Lars von Trier’s apocalyptic 2011 film Melancholia attempts to directly one-up 2001 by launching itself with an eight-minute overture featuring interplanetary shots highly reminiscent of 2001 and set to the most revolutionary composition by another composer named Richard, an artist even more Earth-shaking than Strauss.

Melancholia‘s prologue can stand alone as one of the eeriest and most majestic music videos ever, as it updates an ancient tradition in which the heavens and musical harmony are somehow related.

Unfortunately, the bulk of Melancholia is Last Year at Marienbad-style Euro ennui filmed in the current shaky-cam mode. A transatlantic cast with random accents (Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg, for instance, play sisters) waits around a castle (one with its own 18-hole golf course, as Kiefer Sutherland, peeved over having to pay for Dunst’s disastrous wedding reception, repeatedly points out). Meanwhile, somewhere out there is a giant undiscovered planet, emblematically named Melancholia, which will soon (spoiler alert!) smash into the Earth, extinguishing all life in the universe forever.

As hard science fiction, Melancholia doesn”t even try: None of the characters bothers explaining why there is an unknown planet wandering around the solar system. (Aren”t there laws of gravity against that kind of thing?) Instead, Melancholia makes sense as a tribute to one of European art history’s great leaps into the future.

In his overture, von Trier capitulates the rest of his movie with superbly lit slow-motion shots of key scenes, which he cuts to the beat of that prime source of unearthly modernist music: Richard Wagner’s instrumental prelude to his tragic opera Tristan und Isolde. When this short bit of “music of the future” debuted in 1859, six years before the full opera, it must have sounded to audiences like science-fiction noise. The Cambridge History of Musical Performance points out how the opera’s

pervasive tonal ambiguity and restless chromaticism heightened by suspensions, unresolved dissonances and sequential variation, changed the course of music history, exercising a potent influence on succeeding generations of composers; more than any other work it symbolised the end of one era and the start of another.

Richard Strauss explained: “Tristan und Isolde marked the end of all romanticism. Here the yearning of the entire 19th century is gathered in one focal point.” Today, Tristan seems so exquisite that it makes Strauss’s Zarathustra sound suitable in its post-2001 role as the concert intro for Elvis Presley during the rocker’s late gas-giant phase.

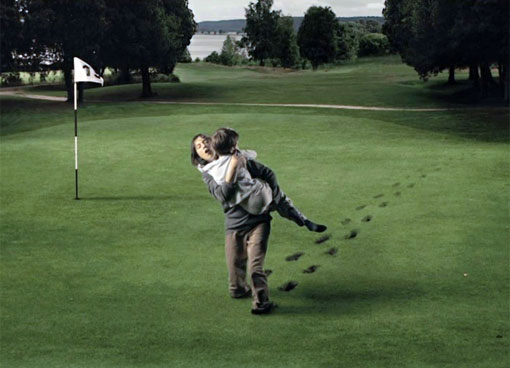

Rather than 2001‘s dawn of humanity, we see our demise in Melancholia‘s apocalyptic imagery, such as a bedraggled Dunst opening her eyes to Wagner’s notoriously unresolved “Tristan chord“ as dead birds fall from the sky; St. Elmo’s fire erupting from her fingers as she poses on a fairway; or a frantic Gainsbourg trying to carry her small son across a putting green that is turning to quicksand due to some inexplicable cosmic catastrophe.