July 22, 2017

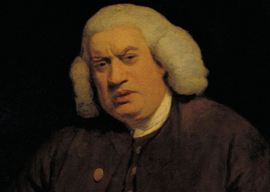

Samuel Johnson by Joshua Reynolds

Some people will be alarmed to discover that, underneath the surface, nothing much has changed in human conduct; but for my own part, I find it more consolatory than alarming. In the first place, I rather like the imperfections of human nature: I find the prospect of a world in which everyone is good, and holds his opinions with precisely the strength that the evidence for them justifies, supposing that justification could be calibrated with such precision, to be very intimidating. And a world in which everyone were beautiful would be a world in which no one were beautiful.

In the second place, knowing that, notwithstanding many changes in his conditions for the better, Man remains Man absolves me of the responsibility of trying to bring about a better species, which seems to be the favorite occupation and ambition of so many of our intellectuals. I won”t manage it, and it is not my fault. I am better advised to confine my efforts to behaving myself with tolerable decency, which in my case is a perpetual struggle. As Dr. Johnson says in the Idler essay about charity:

We must snatch the present moment, and employ it well, without too much solicitude for the future, and content ourselves with reflecting that our part is performed. He that waits for an opportunity to do much at once, may breathe out his life in idle wishes, and regret, in the last hour, his useless intentions, and barren zeal.

Barren zeal indeed! Is that not a description of the favorite state of mind of so many of us? A kind of theoretical zealotry, which never has the opportunity to test its ideas against reality, and knows that it never will, can keep a certain type of mind satisfied for years, decades, and even a whole lifetime. Let the heavens fall, so long as my ideas remain pure!

Such zealotry is not entirely harmless, however. It finds some few who are willing to act upon it, with what results the history of the 20th century (as well as many other centuries) attests. There are some people who prefer the syllogisms of their ideas to the complexities of reality. They are to the world what obsessional housewives are to a house, and they turn a morbid psychological state into a historical catastrophe.

I wish I had more space in which to examine all the ramifications of The Idler apposite to our times; but that would take a book much longer than The Idler itself. Come to think of it, that is one test of good writing: whether it suggests much more than it says.