August 29, 2015

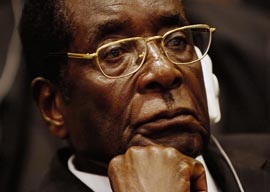

Robert Mugabe

One example of this attitude was that, until quite late in the day, the term “race relations” in South Africa meant not relations between whites and blacks, but between British and Boer. The latter two “races” were the only ones seriously in contention for power, the blacks being considered hors de combat, as it were, destined forever by their natural inferiority to be hewers of wood and drawers of water, incapable of seriously challenging the ruling minority, however small. The victory of the Nationalists in the overwhelmingly white election of 1948 was that of socialism, or perhaps more accurately, corporatism, for one people, namely the Afrikaners. It was designed to solve the problem of the poor whites and to close the gap in wealth, power, and influence between the white South Africans of British and Afrikaner origin. The blacks were nowhere, of no account. It takes little effort of the imagination to understand the humiliation inflicted by this.

If I am right, flattery of Mr. Mugabe, the expression of undying admiration for him on the part of the former colonial masters, the conferral of honorary degrees and so forth, would”or perhaps I should say might, for nothing can be certain about alternative realities”have avoided some of the travails to which he has subjected his unfortunate country. This would have been deeply distasteful to do, of course, because one of Mugabe’s first acts on reaching power was to order the prophylactic suppression of Matabeleland, a potential source of opposition to his absolute power, and far, far worse, in point of unadulterated brutality, than anything done by the regime that his own replaced, supposedly in the name of freedom. I once had a patient whose husband had been tied to a stake, soaked with petrol, and burned alive in front of her by Mugabe’s “activists,” his crime having been to vote for the opposition, and the sight of which had haunted her uninterruptedly for years. I wouldn”t have cared to explain to her why it was nevertheless politic to maintain good relations with Mugabe, for fear that bad relations would make everything worse. For her, nothing could be worse.

But politics is the pursuit of the possible, not the ideal; and the possible is always the lesser evil, not the good. Indeed, in politics the lesser evil is the good, since almost any conceivable policy leads to some evil or other. Nor is politics the mere expression of moral indignation, however justified or gratifying. It is why I could never be a politician, or flatter Mr. Mugabe.