September 25, 2019

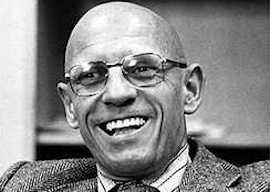

Michel Foucault

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The conventional wisdom of the Great Awokening is in sizable part the dumbed-down heritage of the brilliant and sinister French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926–1984), who happened to be a dead ringer for Austin Powers’ archenemy Dr. Evil. According to Google Scholar, Foucault is the most cited academic of all time.

When Ta-Nehisi Coates, for instance, talks about people who believe they are white doing violence on black bodies via FDR’s redlining, he’s artlessly piling up a number of vaguely recalled affectations of Foucault’s. (Coates confesses, “I loved Foucault but didn’t finish.”)

In his ham-handed way, Coates’ hilarious tic of refusing to admit that white people are white, but instead only grudgingly allowing that they might “believe they are white,” is reminiscent of the hermeneutics of suspicion in Marx, Freud, Nietzsche, and, more recently, Foucault, who never saw a noun he couldn’t put scare quotes around. For instance, on one page of his book Power/Knowledge, Foucault felt the need to put “body,” “children,” “childhood,” and “phase” within quotation marks.

The antiquarianism that has become so prevalent in recent years, as seen in the constant invocations of Emmett Till, New Deal FHA regulations, and 1619, is in part a nod to Foucault’s historicizing flair. The intensely Eurocentric Foucault knew an immense amount about rather dull bureaucratic aspects of 17th- and 18th-century France. He had a knack for disclosing details from dusty royal reports on how to organize hospitals and schools as if they were the smoking-gun evidence in a conspiracy thriller.

African-Americans were once famous for their souls, but now, 35 years after Foucault, they just have black bodies. Foucault loved the term “the body.” In fact, Foucault loved bodies, so long as they were male and engaging in violence, either to him or by him.

Sexual torture was Foucault’s favorite pastime. He was a homosexual sadomasochism fetishist who habituated the bathhouses of San Francisco and thus died of AIDS in 1984. How many men he killed by infecting them with the HIV virus is unknown.

“Power” was Foucault’s favorite word. His woke followers assume that he was of course on the side of the marginalized against the powerful. But if you pay careful attention, you may notice that Foucault saw power less as an illegitimate usurpation than as the capability to get things done.

Foucault was aroused by power, as the title of his book on the history of prisons, Discipline and Punish, ought to suggest.

That Foucault was not a good person was obvious to at least a few leftists. After a debate with Foucault in 1971 on whether “there is such a thing as ‘innate’ human nature,” linguist Noam Chomsky, who is a boyish idealist, like a Jimmy Stewart character of the left, said Foucault struck him as “completely amoral.”

Foucault is often considered a forefather of postmodern identity politics and social constructionism. But it’s not clear that Foucault, who was extremely smart, believed the things his dumber acolytes take for granted.

Note that, considered together, social constructionism and identity politics are fundamentally incoherent. To argue that, say, race does not exist in nature and that black hair must be liberated to be natural is clearly contradictory.

Foucault escaped this conundrum by being radically anti-identity. He saw identities as part of a plot by power to impose categories on individuals.

One interesting contribution Foucault made was to point out that the historical record is unclear whether the type of male homosexual that we are familiar with today existed several centuries ago. There was homosexual behavior, but was there homosexual identity? Similarly, it’s struck me that of all the characters in Shakespeare’s plays, there don’t appear to be any who were written so they had to be played like, say, Jack on Will & Grace.

Because homosexuality doesn’t, so far as we can tell, play an evolutionary role, social constructionist theorizing about homosexuals is less implausible than when discussing basic males and females.

Of course, Foucault’s implication that gays were socially constructed contradicts Lady Gaga’s dogma that they are born this way, because it implies that they could be socially deconstructed. But that’s a forbidden thought these days.

My guess would be that Foucault didn’t like the idea that some men are born this way because that would imply that other men aren’t born this way, which would suggest that he would never get to have sex with those men, a conclusion he found intolerable.

For Foucault, innate identities got in the way of his ideal of polymorphous perversity. In Foucault’s mind, identity was the enemy of anonymous sex and its partner, death. Foucault’s biographer James Miller writes:

In his 1979 essay, he imagines “suicide-festivals” and “suicide-orgies” and also a kind of special retreat where those planning to commit suicide could look “for partners without names for occasions to die liberated from every identity.”

Foucault was one sick puppy.

He reminds me of a gay version of France’s rightist sci-fi novelist Michel Houellebecq crossed with actor Kevin Spacey. But because Foucault was on the culturally dominant left, he has, so far, been in little danger of being canceled.

Foucault, with his labyrinthine prose style, was adept at crafting his sentences to make it hard to quote any single one that nails down his position. It’s hard to imagine that if Foucault had survived to 2019, he would be saying the kind of things his acolytes are declaring along the lines of:

Race doesn’t exist, but Rachel Dolezal can’t possibly be black, while Caitlyn Jenner is of course a woman.

Foucault was much slipperier. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy summarizes his ploy on the sexes:

He critically appraises the idea of a natural, scientifically defined true sex by revealing the historical development of this form of thought. He does not claim that sex, understood as the categories of maleness and femaleness, was invented in a particular historical period. He rather analyses the ways in which these categories were founded and explained in discourses claiming the status of scientific truth, and how this allegedly “pure” explanation in fact constituted these categories so that they were understood as “natural.” This idea has had enormous influence on feminist philosophers and queer theorists.

In other words, Foucault wouldn’t let himself get trapped saying anything clearly stupid, such as that maleness and femaleness were socially constructed. But he didn’t mind if you assumed that his use of scare quotes meant he believed that, as long as you were on his side.

Foucault was an immensely intelligent man who devoted his cleverness to promoting stupidity among his acolytes by delegitimizing distinctions, such as between adults and “children.” Miller writes:

Through…an uninhibited exploration of sadomasochistic eroticism, it seemed possible to breach, however briefly, the boundaries separating the conscious and unconscious, reason and unreason, pleasure and pain—and, at the ultimate limit, life and death—thus starkly revealing how distinctions central to the play of true and false are pliable, uncertain, contingent.

It turned out, however, that even for Foucault, death was not pliable, uncertain, contingent.

Foucault was not all that politically active by the engagé standards of French intellectuals. The son of a Catholic surgeon, he’d been a member of the French Communist Party when young, but became an anti-Communist Gaullist technocrat in the early 1960s. He missed out on the fun of May 1968 by being out of France, but remade himself as a leftist soixante-huitard.

Late in his life, he seemed to be drifting rightward, speaking up for Poland’s Solidarity movement and praising the ideas of U. of Chicago free-market economist Gary Becker. As he spent time indulging his proclivities in the prospering San Francisco Bay area, he perhaps came to see that capitalism and his decadent hedonism weren’t so averse.

One political issue close to Foucault’s heart was American sociologist Erving Goffman’s successful crusade to shut down insane asylums, which liberated the poor lunatics to be homeless and sleep on the sidewalks. (Erving’s daughter Alice Goffman is now a leading crusader against “mass incarceration,” so you know that will turn out equally well.)

Another cause to which Foucault devoted himself was liberating children to have sex with grown men. In France, the age of consent in 1977 was only 15 years old, but Foucault nevertheless signed a petition, along with Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Jacques Derrida, to decriminalize pedophilia.

Foucault did a 1978 radio interview to promote the abolition of age-of-consent laws in France. It’s noteworthy how smoothly Foucault’s usual arguments on other topics service this campaign.

For example, Foucault begins with his usual tactic of making the assertion that history shows that something that might seem like common sense (making child molestation illegal) was only recently socially constructed, so therefore it could (and thus should) be deconstructed:

This regime is not as old as all that, since the penal code of 1810 said very little about sexuality, as if sexuality was not the business of the law….

How do we know, Foucault goes on, that the child didn’t want to be the victim of statutory rape?

It could be that the child, with his own sexuality, may have desired that adult, he may even have consented, he may even have made the first moves. We may even agree that it was he who seduced the adult.

And who is to say who is a child?

In any case, an age barrier laid down by law does not have much sense.

In arguing for the legalization of boy bothering, Foucault never quite gets around to claiming that age is just a social construct, but that’s the mood music.

How much of Foucault’s vast intellectual enterprise of denouncing categorization of individuals as possessing distinct identities was intended to undermine the legal category of children too young to consent? Did Foucault happen to dream up his ideas first and only then realize that his logic proved that it should be legal for him to have sex with boys? Or did he want to have sex with boys first and then dreamt up his vast system of justification?

Foucault himself once said:

In a sense, all the rest of my life I’ve been trying to do intellectual things that would attract beautiful boys.

Foucault was an evil man.

But he was right about something: that power helps you control discourse and controlling discourse helps you have power.

Today, though, it’s Foucault’s fans who have the whip hand.