December 20, 2023

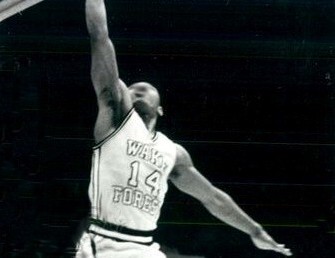

Tyrone Bogues

Source: Public Domain

What’s the most common first name for an African-American NBA player?

D’Qantivious?

Nah, it turns out that black pro basketball players are most commonly named Chris, followed by similarly middle-class names such as James, Marcus, Mike, and Eric.

According to data scientist Seth Stephens-Davidowitz’s new mini-book Who Makes the NBA? Data Driven Answers to Basketball’s Biggest Questions, black NBA players are only about half as likely as the general black male populace to have those bizarre black-only first names that sociologist Andrew Hacker noted tend to be the product of schoolgirl whimsy as teen mothers try to outcompete all their pregnant friends in creative naming.

That’s because the players who make it to the NBA and stay for a solid career tend to come from above-average family backgrounds:

Black NBA players are 32 percent less likely to be born to unmarried mothers and 36 percent less likely to be born to a teenage mother.

Why are 59 percent of African American NBA players legitimate? Because professional sports are extremely competitive these days, so, unless you are seven feet tall, it takes privileges of both nature and nurture to reach the big time.

Also, I suspect that the growth in emphasis on long-distance three-point shooting in recent years has further suburbanized the NBA as the best shooters now tend to grow up with their own driveways in which to practice their outside shot.

This short book contains much of interest for both basketball fans and those interested more generally in how the world works.

The overall theme of the 5′ 9″ tall Stephens-Davidowitz’s Who Makes the NBA? is that:

Basketball feels like a sport that was designed in a lab to maximize its reliance on things that can only be achieved through the right DNA.

For example, the average American man’s hand is eight inches wide from thumb to pinkie, and, no matter how hard you work out, there isn’t much you can do to change that. In contrast, NBA legends tend to be born with huge hands: among those with hands over 11 inches wide are Shaquille O’Neal, Giannis Antetokounmpo, Julius Erving, Wilt Chamberlain, and Michael Jordan. Phil Jackson, coach of the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers, consoled the late Kobe Bryant, a fanatically hard-worker, with the suggestion that the reason he wasn’t quite as good as his idol Jordan was because his hands were smaller.

Of the nineteen NBA draft picks with the smallest hands, the author reports, seventeen turned out worse than their level in the draft would have predicted.

Of course, the most important basketball metric is height. Or to be precise, it’s how high you can get your hand off a standing vertical jump, so a long-armed player is better, all else being equal, than a long-necked one. But height is the most obvious measure of a basketball player, and it is, of course, vastly important:

Each inch roughly doubles your chances of making the NBA—throughout the height distribution…. The probability of a man of below-average height—under 5′ 10″—reaching the NBA is 1 in 3.8 million. The probability of a man over 7 feet tall reaching the NBA is roughly 1 in 7.

If one out of seven men over seven feet tall reaches the NBA, you just have to be a decent—but not great—athlete to be an NBA center. For example, seven-footers do worse on the NBA draft combine’s bench press than six-footers. Also, big men tend to choke more in pressure situations, such as shooting free throws late in playoff games, than do shorter players:

The average 7-foot player shoots clutch free throws 6.3 percentage points worse than they shoot non-clutch free throws.

Guys who were bad at shooting free throws in the clutch include the San Antonio Spurs’ admirable duo of David Robinson and Tim Duncan.

Interestingly, contrary to conventional wisdom, almost nobody shoots free throws more accurately under pressure. After all, shooting a free throw takes less work than anything else a player does, so why not give each one your best effort?

The only player in recent NBA history to shoot free throws better with the game on the line is Shane Battier. Stephens-Davidowitz attributes that to random luck. But Battier was such a subtly effective player that reporter Michael Lewis wrote a basketball follow-up to his famous baseball stats book Moneyball about Battier. So, who knows?

Who is the greatest basketball player of all time adjusted for height? Stephens-Davidowitz’s calculations suggest that if you statistically remove the advantage of height, the best basketball player ever, unsurprisingly, is 5′ 3″ Muggsy Bogues, who played fourteen seasons in the NBA, nine of them as a starter.

Contemplating the extraordinary career of little Muggsy Bogues makes me happy. He is one of the most remarkable individuals in basketball history. On the other hand, the prime reason basketball is such a popular spectator sport is that it exemplifies masculine dominance (which is why the WNBA never catches on). So adjusting away height is kind of pointless. Basketball’s freak-show Goliaths are a big part of what people like about the game.

One finding in the book about the power of nurture rather than nature is that the most notable distinction of the 103 NBA players who have been the sons of previous NBA players is that they make about 80 percent of their free throws, while other players average 75 percent. For example, Steph Curry averages 91 percent, the best mark ever, while his formidable father Dell Curry, who played for sixteen seasons, shot a fine 84 percent. Presumably, NBA dads get the best coaching available to perfect their shooting motion and tend to pass their wisdom on to their sons.

Should high school basketball stars attend a powerhouse hoops college like Kansas or Kentucky to maximize their chances of making the NBA? For the very highest-ranked recruits, it doesn’t much matter where they play their one year of college ball. But:

Lower-ranked recruits who attend an elite basketball program are far more likely to reach the NBA.

Analogously, Raj Chetty recently found that the median income of Ivy League grads isn’t much higher than that of state flagship university grads with identical test scores. But if you want to get a really high-paying job with McKinsey or Goldman Sachs, then you have a much better chance if you go Ivy.

On the other hand,

I found that, while attending an elite university does help lower-ranked recruits get a shot in the NBA, it does not help them become great NBA players. A lower-ranked recruit who goes to a less-elite school is just as likely to become an NBA All-Star as one who goes to an elite school.

An interesting gimmick of this book is that while it took Stephens-Davidowitz three years to write each of his two previous tomes, he got this one done in a month using ChatGPT artificial intelligence.

Only the appendix that explains how he used AI was written in part by AI: The main section of the book is in the same prose style as his previous works. But he found ChatGPT’s dull prose style good enough for rewriting his end papers.

The technique he used for generating the appendix was to jot down sentences in any order, then ask AI to put them in a coherent sequence. After a few back-and-forths, ChatGPT would come up with a pretty decent text.

Nor did AI discover many of the findings in the book. You might think that AI would be particularly adept at crunching through massive amounts of data to find unexpected statistical correlations, but so far the leading AI services are focused more on spewing plausible-sounding prose.

So instead, Stephens-Davidowitz used ChatGPT to quickly handle the more boring data analysis tasks like merging and cleaning data. It also makes nice graphs once you know what you want.

One interesting task the author off-loaded onto his robot assistant came when he was wondering whether guys who had grown up in scary slums were cooler in the clutch. So he asked ChatGPT to look into its vast knowledge base and rate famous NBA players on a 1 to 10 scale of “childhood difficulty.”

It turned out that hood kids and suburbanites were equally affected by pressure. More interestingly, the ratings of childhood difficulty that ChatGPT came up with were “coherent and sensible.” For example,

Allen Iverson, 9.0, “Grew up in poverty in Hampton, Virginia; mother struggled in a crime-infested environment.”…

Steve Nash, 2.0, “Had a comfortable upbringing in British Columbia, Canada, with family support for his sports endeavors.”

Steve Nash, two-time NBA MVP, is an Elon Musk type born in Johannesburg and raised in genteel Victoria, British Columbia.

I have a theory, inspired by Nash and the great John Stockton of Spokane, Washington, that white basketball players in North America thrive best in remote regions where they don’t have to compete against too many blacks until they are more physically mature. My impression is that whites mature more slowly than blacks, so the urban white kids who have to play with blacks as adolescents tend to wind up on the bench, discouraged.

Yet, I don’t really care enough about recent basketball history to search through the data to find out if I’m correct or not. Pretty soon, though, I should be able to ask a robot to do it for me.