October 23, 2020

Source: Bigstock

President Trump was ill with COVID-19; President Trump was treated with certain new and expensive drugs; therefore President Trump was cured by his treatment with those new and expensive drugs, and demand for them will therefore rise. Why should presidents get all the best treatment?

Such is likely to be the effect of his episode of illness, at least if he suffers no relapse, and there will soon be conspiracy theorists who argue that his illness was contrived as a stock-price manipulation (which in my opinion was quite possibly the explanation of why a terrible and scientifically worthless paper about remdesivir in The New England Journal of Medicine earlier in the epidemic was published). There are conspiracies in the world, of course, but not one-hundredth as many as conspiracy theories, because paranoia never lies far beneath the surface of even the most highly balanced person’s mentation. Conspiracy theories appeal to our strongest political emotion, which is hatred.

One of the greatest though generally unsung medical advances of the last century is the recognition of the inadequacy of testimonial evidence. Many diseases are self-limiting in the sense that, left to themselves, patients will get better by natural processes. Moreover, both diagnosis and treatment are frequently probabilistic rather than absolutely certain. Many drugs are given to patients on the basis of probabilities, though the patients to whom they are given often do not understand this. They believe that drugs are prescribed to do them good here and now rather than on a chance, sometimes quite remote, that they will do them good at an unspecifiable time in the future. In addition, few treatments are 100 percent successful, and whether a treatment with a low but definite rate of success, though with unpleasant side effects, is worth taking depends on the seriousness of the disease to be cured or ameliorated. In other words, therapeutics is an art as well as a science, in the sense that it requires judgment as well as knowledge; and patients may differ as to whether they consider a treatment worth the effort of taking it.

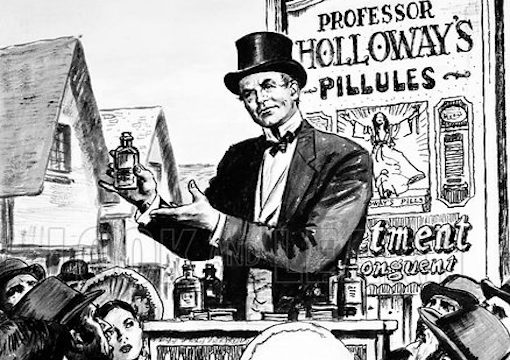

It has long been the case that treatments given to prominent persons with alleged success have been the staple of advertisers. In the 19th century, mass advertising was invented by a purveyor of a patent or quack remedy, Thomas Holloway, who made a vast fortune from the pills and ointment that bore his name and that at least did no harm, unlike the potions of the orthodox doctors of the time. Revenue from advertisements for such medicines was a financial pillar on which rested much of the provincial press, whose owners and editors often doubled as sellers of them to the public. It was an excellent business model, to take revenue both from advertisements and from the sale of the goods advertised, admirably efficient from the point of view of maximizing profits; and in turn the testimonial, real or invented, of General This or Lord That, or some other prominent person, to such and such a remedy for his biliousness, was taken by the public as proof that it worked. The testimonials were an appeal both to social climbing and magical thinking. If one took the same medicines as a prominent person, one somehow became a little closer to, or like, him. Incidentally, roughly half of the advertisements for patent medicines were for the treatment or prevention of syphilis, never mentioned by name.

The attention given to the opinions of prominent persons on matters about which they may be no more qualified to speak than the most ignorant illiterate is rather curious, but I suppose that to protest against it is pointless.

Who counts as a prominent person useful to advertisers changes over time: No one would now use duchesses or earls to endorse a treatment for piles. These days, famous professional athletes earn more from their supposed endorsements of products than they do from their prowess on the field, and I imagine that, from the advertisers’ point of view, such endorsements must be worth the expense. It is possible, I suppose, that advertisers pay for endorsements merely to preempt their competitors, for if they do not pay for such endorsements their competitors certainly will, and thus the value of endorsements is bid upwards, to the benefit of the endorsers rather than of the advertisers. But it is more probable that such endorsements actually increase sales of whatever is endorsed, which is a depressing reflection on mass psychology.

Why should an endorsement of a product, shall we say of a supposed energy drink or balm for chapped lips, affect what people buy? Everyone knows that such an endorsement is about as sincere as a speech by Bill Clinton, having been extracted by the lure of lucre. It represents no genuine opinion, even if the endorsing person’s opinion were worth having in the first place, which is never the case. Is there no limit to human gullibility?

The problem is not so much a cognitive one as emotional. The person apparently taken in by such endorsements is more the victim of false hope than of misleading information. He hopes by some magical process to be more like the endorser if he buys what the latter has endorsed. Endorsements by admired persons appeal to the Walter Mitty in people who lead lives of quiet (or even noisy) desperation. In England, you often see grotesquely fat men approaching middle age who can barely manage a slight incline of 10 yards without breathlessness, or for that matter without taking alcoholic refreshment en route, dressed in tight football shirts bearing the name and number of some famous soccer player who drives a yellow Ferrari and is surrounded by pretty girls competing for his notice. If the player wears the shirt, then wearing the shirt will turn the wearer into the player. Never mind that the player (a) has talent, (b) possesses the determination and willingness to work hard to take advantage of it, and (c) is fifteen or twenty years younger. The shirt is like a winning lottery ticket of fantasy.

Insofar as this mentality is indicative of a hopeless longing, that is to say of genuine suffering, we—who deem ourselves superior to and immune from it—should try to sympathize with it rather than merely mock it. Never forget:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave,

Awaits alike th’inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Embargo and Other Stories, Mirabeau Press.