June 01, 2019

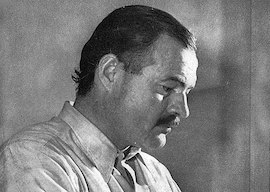

Ernest Hemingway

Source: Wikimedia Commons

I didn’t like it, and then I liked it. But a writer’s job is to tell the truth, as Papa said back in 1942. Hemingway maintained that it was bad luck to talk about writing—“it takes away whatever butterflies have on their wings”—but he wrote nonstop about writing, as incisively about the subject as any writer ever did. Last week I finished my umpteenth book on Papa, and it depressed me to no end. Really. And then, just as I was reading the last three pages, I found out that I did, after all, have a connection with the great Papa, and my depression lifted like the fog.

Life is one long coincidence, and just as I had picked up Autumn in Venice, about Papa’s last muse, Debbie Bismarck rang me from Key West because she and her husband had thought of me while visiting Hemingway’s house there. Actually, it was Pauline’s house, inherited by Gregory, their son, who although not gay was a cross-dresser. (Go figure.) Some older readers of this column may remember that I had met Hemingway when I was a 15-year-old—had drinks with him in a New York bar and got loaded—but then it turned out he was a phony Papa, an older heavyset man with a white beard posing as the greatest writer in the world.

Modern crap writers and victimhood-culture opinion makers no longer have any time for the great Papa. If they did, he’d go down in my estimation. Yet it’s hard to overestimate the effect that Hemingway had on prose style, although that’s also disappeared with the modern crap published today. Papa stripped sentences down to their essence, cleared away the lush density rooted in Victorian prose, and in the process became numero uno and has stayed there ever since. The book that got me depressed, about Papa’s last muse in Venice, was written by Andrea di Robilant, a man I once met at a party and did not like at all. He had an arrogance about him that brave soldiers, good fighters, and real tough guys do not possess. Gigolos, dress and shoe designers, and modern celebrities have it in spades. I used to know his uncle, Carlo di Robilant, quite well; he was an Agnelli acolyte, a typical lefty of that time (the ’60s), scared to death his family’s ass-licking of the Duce might be an embarrassment.

Reading the work about Papa’s last muse and last days made me change my mind halfway through. It inspired a cognitive frenzy, actually, as I realized I knew some of the protagonists, especially the then 17-year-old Afdera Franchetti, whom I later met as Afdera Fonda and with whom I have remained good friends to this day. Afdera, when young, gave interviews that Renata, the heroine of Papa’s worst book, Across the River and Into the Trees, was based on her and that Hem was in love with her. And there were others mentioned I knew not well.

There was a time I contemplated applying to Mastermind about Papa. Now I know better. What I didn’t know was how incredibly generous Papa was with friends and strangers alike. He single-handedly supported the Ivancich family, and lavished large amounts to his “daughter,” as he called her, Adriana Ivancich. He employed and helped her brother Gianfranco, gave large parts of his Italian earnings to Adriana, and spent even more on gifts to his wife Mary, out of guilt, despite the fact he had not even tried to bed Adriana.

When Papa got the news in Cuba that Adriana had met a man who did not allow her to keep up their almost daily correspondence, he did nothing about it but continued his munificent ways with her. That’s where I come in: Papa thought she had met a young Italian of her class, but it turned out the man in question was a Greek, Spyros Monas, “who owned coffee and hemp plantations in Tanganyika.” He was waiting for an annulment when he proposed to Adriana. They divorced after five years, and then he took up with F.L., the daughter of a French ambassador and a very sweet and innocent girl that I had gone out with for quite a while. I remember this jerk—no longer with us—because he used to try to stare me down whenever we’d run into each other at parties. He was obviously a masochist and had asked a lot of questions about F.L’s past, and she was naive enough to tell him. His vile stares ended when I put my face an inch from his and told him a punch in the nose is better than 1,000 hard looks. He got the message. And I finally had my connection with Papa, although ignorant of it at the time.

Autumn in Venice recapitulates the great physical courage of Hemingway after his double plane crash and terrible injuries, his brave stand against wild animals while waiting—without weapons—to be rescued; and his soft “Papa” side toward the weak and the women. Today’s midgets stand in reproachful contrast to his he-man shenanigans, his excessive drinking, his bravado, his fantastic talent. His great taste in women—not Mary, his last one—and in his houses: the light, white, and airy Cuban abode, and his flat at the Sherry-Netherland, where Taki grew up. As he might well have said, “I shit on all his critics, Gertrude Stein and other such phonies, and declare Papa the King of the World.”