October 18, 2019

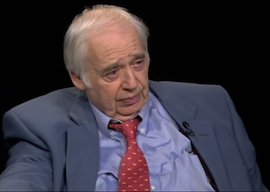

Harold Bloom

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The cultural levelers lost a formidable foe this week, the literary critic Harold Bloom dying on Monday at 89 years old. Bloom was still teaching at Yale, where he had spent a distinguished half-century.

His was not, however, an uncontroversial career, for against the Marxists, feminists, queer theorists, and other members of what he fittingly called “the School of Resentment,” Bloom affirmed the value of literature on its own terms.

Unlike his friend and Yale colleague, the late poet-critic John Hollander, Christopher Ricks, Marjorie Perloff, and other peers, Bloom did not, even in his fine, early close readings, have much to say about matters of literary form. Nevertheless, he understood that literature, like all art, is always something wrought, the product of a serious artist’s disciplined craft and conscious intent. And he nobly resisted the reduction of literature to issues of class, sexism, racism, history and context, and all the fashionable rest.

To read in the service of ideology, Bloom insisted, is not to read at all. Like sports, art is essentially competitive, a fierce and unforgiving agon; and if it is the purpose of writers to outdo one another as they strive to achieve greatness, it is the purpose of critics to distinguish good writing from bad. Literature, then, is by no means some party where everyone is welcome. Rather, it is exclusive or nothing at all, and critics must indeed evaluate and rank.

Of course, this principled and now, alas, old-fashioned stance, although it is merely what should be expected of a man who considers himself a literary critic, made Bloom many enemies in the leftist academy; and he spent most of his long career at Yale teaching outside of the English department, “a department of one,” as he used to say, so as not to be at constant odds with the theorists, “lemmings,” and “resentment-pipers.”

There is a lovely 2009 video of Bloom reading aloud Wallace Stevens’ poems “Tea at the Palaz of Hoon” and “Like Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery.” Bloom is alone, old, and grave, the inner passion and intensity that drove him palpable. The last two stanzas of the first poem read:

Out of my mind the golden ointment rained,

And my ears made the blowing hymns they heard.

I was myself the compass of that sea:

I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw

Or heard or felt came not but from myself;

And there I found myself more truly and more strange.

Our very selfhood, the speaker says, is one with life’s beautiful strangeness and wonder. This is Stevens at his most characteristic—celebrating life’s imaginative splendor, and elevating the reader thereby—and when he recites these exalted lines, Bloom’s inspired manner properly becomes more elevated, and conveys something of his own lofty spirit.

(Stevens, incidentally, was a Taft Republican from Reading, Pennsylvania. Like T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost, and Ezra Pound, he was a cultural and political reactionary, and like those greats, he’d have his work cut out for him trying to rise to eminence in our age of gatekeeping levelers.)

Literary criticism took a theory turn in the 1970s, and in 1973 Bloom published his book The Anxiety of Influence. Like everything Bloom wrote, it is deeply erudite, and like much of what he wrote, it is profoundly eccentric, full of esoteric ideas and terms taken from psychoanalysis, Kabbalah, and Gnosticism. The book’s central claim, following after Freud’s notion of the Oedipus complex, is that writers must achieve greatness by fighting free from the sometimes crippling influences of their predecessors, those terrible father figures and anxiety-inducers. Not only that, but writers must, again, reckon with their predecessors’ achievements: Cormac McCarthy must measure himself against William Faulkner, who had to measure himself against Herman Melville, who measured himself against Shakespeare, and so on.

No doubt there is much to this rather masculine perspective. Writers learn their craft, after all, by reading other writers—typically, previous writers—and all ideas of value are inevitably comparative. Bloom tended, though, to exaggerate the anxiety of influence. Ricks got this quite right when he wrote that “Bloom had an idea; now it has him.” Every literary work, Bloom declared dogmatically, is the result of a creative misreading. For Bloom, there is no work that is not trapped in a struggle with some precursor or precursors. Often the process is unconscious, nor should we trust what the writer himself has to say about the matter, his anxiety being likely to produce some kind of “defense mechanism.”

Now, this is all rather excessive and neurotic, for surely not every work unfolds in this vexed fashion. While it may be true, as Emerson said, that the originals themselves were not original, some works are just meant to be what they are; and there are, moreover, fairly original and self-assured writers, people who do not write, whether consciously or unconsciously, in the shadows of towering influences.

Certainly we cannot understand Bloom’s criticism without reference to his Jewishness. As with the views of Marx and of Freud, to resist the anxiety of influence is to confirm its veracity, according to Bloom. Although he was an unbeliever, Bloom was, as he often said, very Jewish, and as Camille Paglia and others have pointed out, with his charisma and mythmaking, with his vatic pronouncements and devotion to “the canonical” in the literary domain, Bloom was more like a rabbi than a literature professor.

Born into a working-class family in the Bronx, Bloom experienced a good deal of anti-Semitism at Yale, so much so, he claimed, that he was nearly denied tenure there. It seems clear, at any rate, that Yale was a formative influence on Bloom’s thinking. In his excessive claims about the anxiety of influence, I have always sensed something of his own class anxiety in the highly competitive Ivy League. An ambitious character, Bloom set out to make a name for himself when the WASP elite was still a significant cultural force. And he seems to have read some of his own frenetic publishing anxieties into the general realm of letters. As it happens, in graduate school my academic adviser was a former student of Bloom’s, and like me, he saw some personal projection in the reductive conception of literary struggle.

As a scholar-critic, Bloom made his mark through studies of Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Butler Yeats, Wallace Stevens, and William Blake. With his vast reading and superb memory, Bloom was adept at showing how certain works grew out of other ones, and the intimate relations of literary works generally. His own precursors, he said, were his former teacher M.H. Abrams, and the critics Walter Jackson Bate, Northrop Frye, and Angus Fletcher. Bloom never acknowledged T.S. Eliot as an influence, and given that, as well as his unrelenting hostility to the great poet-critic, it is a safe bet that Bloom was in fact much indebted to him.

Indeed, in the important 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” Eliot argued that writers can be fully understood only with respect to their predecessors. Writing derives from past writing, but new writing also changes the nature and meaning of the tradition. For Eliot, as for Bloom, literature is a dynamic, intertextual process. Bloom stressed that a writer himself, and his approach to writing, can be changed by his new work, but it may well have been from Eliot that Bloom—no strong creative writer himself, despite his efforts in composing weird, Gnostic fiction—learned that literature is so very dynamic in the first place.

Bloom wanted a lot of readers, and with his popular books written for a general audience, he got them. Of these books, the most important is The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages (1994). It covers Shakespeare, Milton, Ibsen, Kafka, Virginia Woolf, Samuel Beckett, and other major Western writers. It is, above all, Bloom’s noble stand against what he called “amateur social work,” that is, the vulgar leveling that would have us read books because the author is female, black, gay, or whatever. As Bloom rightly said, the idea that you do someone some sort of moral good by reading him for reasons of identity politics is one of the strangest ideas ever to come out of academia.

Although he was a lifelong man of the left, Bloom was not prepared to sacrifice aesthetic merit—and the elitism on which it depends—for the sake of “equality,” “inclusion,” or “diversity.” Besides the excellent commentaries on Wordsworth, Tolstoy, and others, the book is rife with wonderfully mordant shots at leftist levelers. For instance, about feminist-queer literary scholars, Bloom writes: “Cheers for Emily [Dickinson], cry the pom-pom wavers; she slept with sister-in-law Sue!”

Bloom’s friends and former students numbered some distinguished literary figures. Still, in our time, no writer has even come close to matching the ferocity and persistence with which Bloom opposed the corruption of literary standards. In fact, few writers have anything to say about this. It may well be that writers—and their agents and editors—are afraid of scaring away potential readers. Anyhow, enough writers, we must hope, will be like Bloom and refuse to compromise.

Will they do so? It is an interesting question, an anxious question. Over the years, as literature became so politicized, Bloom became skeptical of the value of literary awards, and dismissive of certain literary reputations. On Oct. 8, The New York Times published an unintentionally funny review of Ben Lerner’s celebrated new novel. “To Decode White Male Rage,” says Giles Harvey, Lerner “First Had to Write in His Mother’s Voice.” Lerner, an avowed writer of autobiographical fiction, is the son of two Jewish psychologists, and the more I learn about his background and opinions, the more he seems to me a parody of a Jewish man who was emasculated by his neurotic, progressive, perpetually concerned mother.

In his fiction, as in his interviews, Lerner makes it quite clear that he regards his white race and his male gender as “problems,” or rather, “problematic.” His new novel, The Topeka School, appears to be about how his mother—bless her heart!—kept him from growing up to become a mansplainer and a problematic white man generally. I say “appears” because, although I enjoyed parts of Lerner’s previous two novels, I was not able to get through the latest, it being marred by passages like the following, in which the narrator Adam (modeled on Lerner himself, as in the first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station) confronts another father on the playground regarding the man’s child’s behavior:

I’ve been asking for your help in making the playground a safe space for my daughters; I recognize that my reaction to your son is not just about your son; it’s about pussy grabbing; it’s about my fears regarding the world into which I’ve brought them.

The other father declines to intervene. Then Lerner, in his omniscient authorial voice-over, writes parenthetically:

I helped create her, Ivanka, my daughter, Ivanka, she’s six feet tall, she’s got the best body, she made a lot of money. Because when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.

Lock your doors, O fair sex—Donald Trump and the pussy grabbers are on the loose! From the parody of the president to the view of masculinity as “entitled” and “toxic,” this passage is mercilessly trite. It reads like committee-writing—say, by the local Women’s Studies Department—and Lerner, we are reminded, is a product of the MFA scene. In this bland paranoia, we have what right-thinking people are supposed to think concerning Trump and the #MeToo movement. It’s as stale as the latest Democratic debate.

To be sure, Lerner is capable of inventive, elegant, and funny sentences. But for all that, there is a dreadful failure of imagination in the creation of his characters. Lerner seems boringly incurious about those who are not like himself, forever placing people into certain familiar categories. Thus, his characters, far from being distinct, rounded, and absorbing, are flat, predictable types: the artist who is agonized since he feels inauthentic, the sensitive male who loathes his own sexuality, the feminist mother keen to prevent her son from growing up into a “pussy grabber,” and so forth. This may work for a lowbrow TV show, but it’s fatal to serious art.

As a critic, Bloom emphasized that the primary characteristic of canonical writing is strangeness. By this, he meant an overpowering originality that allows us to see what we would not see without the writer’s particular vision. Such insights are mysterious, the gift, the grace of genius. Lerner’s new novel bears the stamp of what Bloom would have called a period piece. It features Lerner’s usual criticisms of “capitalism,” but in keeping with his general shallowness—with his habit, as it were, of scoring points on the cheap—he never mentions the fact that Socialism and Communism have always turned out to be disasters.

Nor is human nature in a large sense or the nature of animal existence itself an obstacle for Lerner. For he never goes into such messy depth, but sticks to facile structural critique. It’s true that Lerner indicts male heterosexuality, but this seems merely conformist—what writers are expected to do these days, as we’ve long seen from Jonathan Franzen, David Foster Wallace, and others—and again, shallow insofar as Lerner lets women off the hook, as if they were beyond reproach.

Even Lerner’s appearance—flabby, androgynous, square nerd glasses—is a left-wing cliché.

If writers wish to do vital work, and set themselves apart from the crowd—including the largely middling literary crowd that decides whom to publish and to award—they should practice the hardheaded aesthetic autonomy that Bloom cherished, while men like Lerner diligently fill up the dustbins.