January 25, 2023

Source: Bigstock

Traffic fatalities, like murders, should be in steady decline due to improving technology and big data analyses of danger spots leading to better policing and infrastructure. That’s happening in much of the world, but not in the U.S. in this decade.

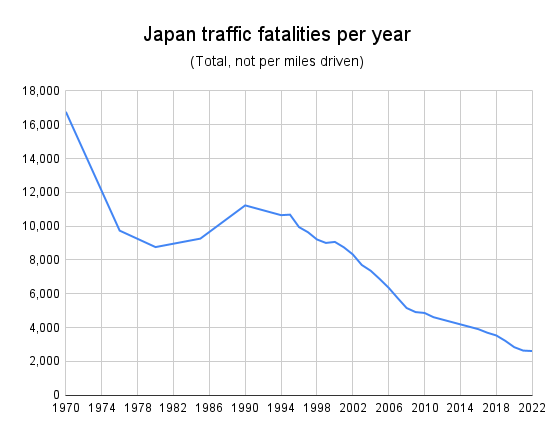

For example, in a serious country, Japan, in 2022 total motor vehicle accident deaths declined for the sixth straight year to 2,610, and are now down 19 percent from 2019 and 84 percent from their peak in 1970.

Notice that the Japanese government announced their year-end figure on Jan. 4, 2023, while it will be several months before the U.S. government releases a comparable number. In contrast, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration released on Jan. 9, 2023 its early estimate of road deaths for the first nine months of 2022.

I don’t have full 2022 figures yet for countries other than Japan, but most major first-world countries saw very different changes in total road deaths from 2019 to 2021 than did America:

U.S.: +19 percent

Canada: +1 percent

Australia: –3 percent

Italy: –9 percent

France: –9 percent

U.K.: –11 percent

Germany: –16 percent

Japan: –18 percent

Any statistic that got worse in 2020 is automatically blamed by the American media on Covid, but it sure looks like America’s unique boom in carnage on the pavement and on the sidewalk was more related to its indigenous Floyd Effect than to the global pandemic.

And the Japanese are continuing to work on getting safer, announcing mandatory driving tests for renewing driver’s licenses for those 75 or over with moving violations, even though the aged make up a large chunk of Japanese voters. In contrast, when my father was 91, he passed a written test to renew his California’s driver license for five years until he was 96. (His view was that by that age he’d be up to eighty years of driving experience.)

With Japanese road deaths down only 1 percent in 2022, it looks like it could be a very close run thing whether Japan meets its long-standing goal of fewer than 2,000 road deaths by 2025. Their count fell 605 over the past three years and would have to fall another 611 over the next three.

But at least 2,000 was a reasonable goal for Japan to set. In contrast, American states and municipalities have tended to adopt the preposterous Vision Zero goal of eliminating all traffic fatalities, while also pandering to Black Lives Matter by reducing police stops of bad drivers.

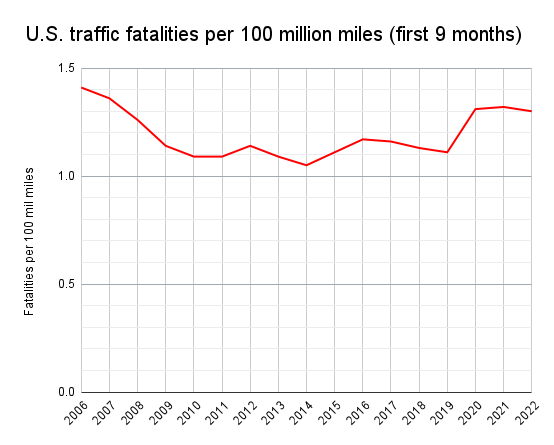

Not surprisingly, the result for the first nine months of 2022 is a 33 percent increase in total motor vehicle accident deaths since Ferguson in 2014. Measured per 100 million miles driven, American traffic fatalities in 2022 were up 24 percent since the same time period in 2014.

Fortunately, deaths per mile in the U.S. dropped a little under 2 percent in 2022 compared to 2021.

Unfortunately, deaths per mile are only back down to about the disastrous 2020 level, a year in which deaths per mile driven soared 18 percent, with most of the increase following George Floyd’s death in May.

A recent report by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety offers some clues about what went so wrong on the road in 2020.

Most strikingly, deaths were up only 0.5 percent among drivers with valid licenses, while they soared 45 percent above the AAA’s model for those without valid licenses:

Drivers without valid licenses accounted for almost the entirety of the increase in driver fatal crash involvements in May–December 2020 relative to the corresponding forecast.

What happened?

Depolicing. The Establishment made clear to cops after George Floyd’s death that they shouldn’t be pulling over so many bad drivers, so bad drivers without licenses felt empowered to drive badly.

To cite an extreme example, Reuters did a deep dive into police activity in Minneapolis:

In the year after Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020, the number of people approached on the street by officers who considered them suspicious dropped by 76%, Reuters found after analyzing more than 2.2 million police dispatches in the city. Officers stopped 85% fewer cars for traffic violations. As they stopped fewer people, they found and seized fewer illegal guns.

Not surprisingly, traffic fatalities in Hennepin County were 48 percent higher in 2021 than in 2019 and homicides in the city of Minneapolis were up 102 percent over the same years.

In parallel to the car-crash trend line moderating slightly in 2022, my recent quick and dirty review of 2022 homicide counts in important cities showed a modest decline in murders from 2021, but only back down to the level of the first year of the racial reckoning, 2020. As I’ve been pointing out since 2021, in this century, trends in homicides and auto deaths have been closely correlated, almost certainly due to politics-driven rises and falls in how proactive the police are.

Many people assume that they don’t have to worry about the rise in crime because they drive everywhere, but these days, the two comparable-sized causes of death go up and down together.

Rather than a “spike” in car crashes and shootings, we are now on a plateau with this decade considerably worse than the last. (Unsurprisingly, the best recent year for crime and crashes was 2014, which is when Black Lives Matter emerged at Ferguson.)

The NHTSA reports that after urban car crashes roared upward during the mostly peaceful protests of 2020, they improved somewhat in 2022, while rural deaths were up instead last year.

One bit of good news about 2022 is that blacks appear to have improved their driving after falling apart during the George Floyd “racial reckoning” when cops were informed that they should stop hassling blacks so much for breaking the law.

The NHTSA only occasionally breaks outs traffic deaths by race, while the CDC does all the time. However, the CDC puts a six-month lag on reporting causes of death, so the CDC’s WONDER database is only current through the end of June 2022. And nobody yet has published an estimate of miles driven in 2022 by race, so the CDC numbers I report below for the first half of 2022 will be per capita rather than per mile.

Blacks started driving very badly around the time of George Floyd’s death, and by the first half of 2021, they were dying 39 percent more in car crashes than in the first half of 2019 (a.k.a. the Good Old Days). But they got 11 percent safer in the first half of 2022 compared with the same months in 2021, and are now down to only 24 percent more fatalities than in the same half of 2019.

Which is still bad.

Likewise, blacks died about 5 percent less by homicide in the first half of 2022 than in the same time span of 2021, but that’s still up 36 percent over 2019.

White traffic fatalities are up 8 percent over 2019, as are their homicide victimizations.

At this point, the most worrisome trends are among Hispanics. They didn’t suddenly go nuts on the highways in 2020 like blacks did, but they keep getting worse ever since. Latinos died on the roads 33 percent more in the first half of 2022 than in 2019. And they died by homicide 47 percent more in the first half of 2022 than in the comparable period of 2019.

A little-known fact is that Hispanics started behaving better after the early 1990s both in terms of traffic and homicide fatalities per capita, and especially better after the 2008 financial crash drove many of the more marginal Latinos back south of the border. My impression is that Hispanics can learn that the authorities don’t appreciate their knuckleheadedness and reform some of their ways, but the politicians, media, and cops have to make that very clear to them.

When American elites stopped being serious about crime in the 1960s, Latinos appear to have responded by doing more crime. At some point in the 1990s, though, they started to get the message that the gringos were gravely tired of it and started to do better relative to both blacks and whites.

Something similar appeared to have happened to reduce the longtime plague of Mexican-American men driving drunk.

Anecdotally, I can recall a number of years ago overhearing two young men who worked at a big-box store in Burbank conversing on break. The Armenian was explaining to the Mexican that they changed the laws so that now a DUI arrest costs $10,000 all told. Wide-eyed, with none of the macho fatalism I would have expected from a Chicano in 1980, the Mexican kid nodded along earnestly with a look on his face that said: “Armenians know about money, so I’d better pay attention to what he’s saying.”

But progress isn’t inevitable. It mostly happens when whites demand it of Latinos. So, when liberals became overwhelmed by white guilt in 2020, Hispanics slowly started to get the message that they could regress without being hassled so much by the law.

Latinos didn’t respond as immediately in 2020 to elites’ anti-police messaging as blacks did, but over the course of 2021–22 their behavior has slipped quite a bit. For example, in heavily Hispanic Los Angeles, road deaths are up 31 percent from 2020 to 2022.

But nobody is talking about these unfortunate Hispanic trends.

Yet, now that we are up to 63 million Latinos, studying what makes them behave better or worse seems prudent.