May 10, 2014

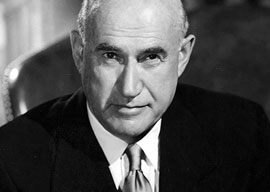

Samuel Goldwyn

For some of you younger readers the name Schmuel Gelbfisz will not ring a bell. Yet back in the 30s, Schmuel Gelbfisz’s identity was a dinner party quiz, and the one who guessed correctly would receive a kiss from Mary Pickford—America’s sweetheart—if he happened to be a man, or an expensive trinket if a lady got it right. Schmuel was born in Warsaw, Poland, in July 1879, a Hasidic Jew, but later allegedly falsified his birthday in order not to serve in the czar’s army. He left my favorite country as a 16-year-old and walked to … Germany. He had no money and no friends, got to the Oder, fell into the water, was fished out by border guards, talked a good game, walked another 200 miles to Hamburg, then made it to England, then the United States. When Gelbfisz died on January 1974, President Nixon had paid him a visit on his deathbed and headlines announced his passing. He was, of course, the last of the great independent producers of Hollywood, a giant of the industry better known as Samuel Goldwyn.

If Sheridan had not invented Mrs. Malaprop, “Goldwynism” would be the word that identified the misuse of language in the dictionary, although many of these were misattributed to him by legend. I will give you just a few of them, having just read a magnificent biography of the mogul by Scott Berg, a very talented writer whose brother is a top Hollywood agent with whom I broke bread in Cannes last year following the premiere of the greatest movie ever, Seduced and Abandoned. Long after he had become fabulously rich and famous, Goldwyn would proudly show his art collection to his guests, always zeroing in on his “Toujours Lautrec.” When his wife suggested a friend should seek psychiatric help he interrupted with, “Anybody who goes to a psychiatrist should have his head examined.” His most famous Goldwynism was “Include me out,” which he sprang on his board that included Averell Harriman, a lifelong friend. Charlie Chaplin and countless others including Douglas Fairbanks claimed that they were present at the creation, such was the beauty of that particular malapropism. When a director complained about the lighting, Goldwyn told him, “You gotta take the sour with the bitter.” He admonished his banker, who was complaining about overruns in the budget, that “We are dealing in facts, not realities.” When absent from his office he told his secretary that “I’ve been laid up with intentional flu,” and when some eager beaver producers tried to hustle him in financing a project, he resisted by telling them, no, “I would be sticking my head in a moose.” He was also the author of the all-time favorite, “A verbal agreement is not worth the paper it’s written on.” Early on in his career he warned his director that “This whole damned picture will go right out at the sewer,” and much later, when the grand Bill Paley took him shooting in his Long Island estate and told Sam, “Look at the gulls,” Sam answered, “How do you know they’re not boys?”

When he gathered all the musical talent in Hollywood, including Leopold Stokowski, George and Ira Gershwin and others, he told them “All this modern music you like is so old-fashioned,” and then pronounced that Dostoevski would be his musical director. “You mean Stokowski,” said Vera Zorina, a great beauty Goldwyn was mad about. “No, I mean Dostoevski.”