March 31, 2020

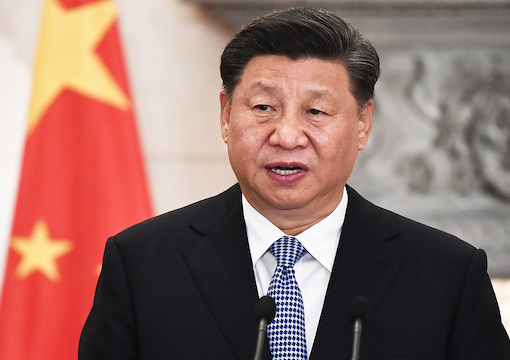

President Xi Jinping

Source: Bigstock

Well, I’ll be damned; the Chinese are now encouraging “cultural appropriation”! After telling whites that they can’t cook “Asian” food or open “Asian” restaurants or wear “Asian” clothes, because everything that comes from Asia belongs to Asians only, the Chinese are now willingly surrendering credit for the COVID-19 virus, even though it came from China as the by-product of specifically Chinese customs.

Sorry, pallies. You want ownership of the pot sticker, you get ownership of COVID.

There are times to avoid pointing fingers, and there are times to point them so vigorously that you put someone’s eye out. So let’s do some pointin’.

COVID-19 is zoonotic, meaning it jumped from animals (in this case, bats) to humans. You’re going to hear a lot of media propagandists claim that “we don’t know the origin of the virus.” That’s pure obfuscation. True, we don’t know how bats originally acquired the virus in the wild. But that’s not the issue; the issue is how the virus jumped to humans (a “zoonotic spillover”). And regarding that “jump,” we know exactly where it happened: at a Wuhan “wet market” where exotic animals are sold for food in the most appallingly unclean conditions. That’s where the “jump” occurred.

Officially, COVID-19 is called SARS-CoV-2. As the name implies, COVID-19 is a relative of another coronavirus, SARS. Remember SARS? It was all the rage in 2003. SARS also did the zoonotic jump to people through the Chinese wet markets. And back in the early 2000s, the media was willing to say so. “SARS was not an isolated outbreak,” reported CNN in 2005. “South China has long been the epicenter of pandemic flus, giving birth to three or four global outbreaks a century.”

And why?

South China offers the most exotic fare from all over the globe—by some accounts at least 60 species can be found in any one market—thrusting together microorganisms, animals and humans who normally would never meet. This thriving trade gives the manufacturing hub that straddles the Pearl River Delta the unenviable title of being the “petri dish” of the world.

In an attempt to control the SARS outbreak, the Chinese government tried to stem the trade and consumption of exotic animals. But again and again, the people of China said no. This bears repeating: The Chinese government acknowledged that the SARS “jump” happened because of the wet markets, and those markets were closed…until the Chinese people brought them back.

As Jacques deLisle, director of the Center for the Study of Contemporary China at UPenn, wrote in 2004:

As the SARS crisis came under control, measures to stem the consumption of civets and other wild animals showed signs of eroding once the intense international scrutiny that proponents credited for their adoption began to abate. A hotly debated Guangdong provincial draft law omitted a ban on consumption of wild animals (beyond mere exhortations not to eat them), and a proposed provision prescribing a ban included no penalties. Reports of the reopening of exotic animal markets, the return of wild animals to menus, and amendments to relax regulatory restrictions became commonplace.

At a 2003 Brookings Institution conference on SARS, Newsday’s science correspondent Laurie Garrett observed:

There was a survey done—50% of responders China-wide said that they do occasionally eat exotic animals. So if you have something that is that entrenched in the diet and the cuisine and the tradition and the culture, I don’t think that any regulation is going to make the actual trade in these animals disappear. If anything, it could drive them further underground and make it harder for public health authorities to have any idea what’s going on. So I don’t think that China has come up with an answer on how to stop zoonosis.

Garrett was incorrect. China knew exactly how to “stop zoonosis.” The government simply lacked the will to fight its citizenry on the issue.

In 2003, the CDC’s Daniel DeNoon made the following prediction: “Will SARS come back? Experts agree only on this: It won’t be the last worldwide killer epidemic.” DeNoon quoted the WHO as saying that this future “killer epidemic” is “especially” inevitable because “in China there has been no attempt to segregate exotic animals in the marketplace. These animals have been allowed back into the markets and are still a threat.”

The timeline is important. SARS became a global menace in 2003. The Chinese government attempted to end the wildlife markets that year…and that same year, the markets came back. Literally, the Chinese couldn’t go four months without their filthy, disease-spreading fare. In fact, the return of the wet markets in 2003, while the world was still struggling with SARS, surprised even the China-friendly WHO. As Science magazine reported in August ’03:

The lifting of a 4-month ban on civets and 53 other species of wild animals delighted gourmets in Guangdong Province, where the local cuisine relies on a variety of wild animals. But it came as a surprise to the World Health Organization, which has a team of experts working with its Chinese counterparts investigating a possible animal reservoir of SARS.

As world health officials were trying to curb SARS, the locals were inviting it. “Chinese Diners Shrug Off SARS: Bring On the Civet Cat.” That’s a New York Times headline from December 2003:

It was lunch hour at The First Village of Wild Food, and if anyone in the restaurant was worried that SARS might again be spreading in this city, they were not showing it. Huang Sheng was more worried about which of the small animals in black metal cages would become his midday meal. Asked if he worried about eating wild game in light of SARS, Mr. Huang said he saw no risk. “It’s no big deal. It’s not a problem.” He said Guangdong Province residents had a reputation for eating exotic foods, a taste not even SARS could deter.

Not even SARS could deter. Nor the threat of the next “killer epidemic.” Nor the words of experts like the University of Hong Kong’s Moira Chan‐Yeung, who in November 2003 addressed this message to the people of China: “Abandoning the widespread use of exotic animals as food or traditional medicine and the practice of central slaughtering of livestock and fowl will decrease the chance of viruses jumping from animals to humans.” Around the same time, Nature magazine’s Asia-Pacific correspondent David Cyranoski rhetorically asked, “Why does this region keep throwing up viruses that have the potential to threaten the lives of people around the world?” The answer? “The southern Chinese widespread use of wild species for food and traditional medicine.”

As the Chinese people fought for their right to spread zoonotic diseases, Chinese activists fought to keep the West from noticing. Victor Wong of the Vancouver Association of Chinese Canadians gave a talk in May 2003 in which he downplayed the need to take SARS seriously: “I contrast SARS with the fact that thousands die from influenza every year in Canada. Around the world, millions die from tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS.” He urged an end to “wall-to-wall coverage of Asians wearing masks, patients being wheeled away on stretchers, health officials in moon-suits” because such stories “only serve to fuel more public panic.” He demanded that the media stop running stories with a “negative message” about how “the Chinese eat exotic wild animals.” Finally, he stressed the need to study not the disease but the “trauma” the coverage inflicts upon the Chinese.

In January 2004, SARS reappeared in China. The wildlife market ban was repealed in August 2003, and five months later, the Chinese had ushered in a new round of the disease. As NBC reported in January ’04, even as the ban was reimposed, wild animals were nevertheless “back on the menu” in Chinese eateries. Many in the Western press treated the return of the wildlife markets as a joke. A January 2004 Slate piece by Wired’s Brendan Koerner stated, “Considered a culinary treat in southern China, the animals are believed to carry the virus that causes SARS. What’s a civet cat, what’s the best way to cook one, and what do they taste like?” Yes, Koerner provided recipes for the disease-carrying animal. I’m sure that seemed hilarious at the time.

In a July 2004 piece about the revocation of the January wet-market ban, the L.A. Times wondered “whether the virus for another potential outbreak might be lurking somewhere else in the Chinese diet.” However, the WHO, which had been against the ban’s August 2003 repeal, by July 2004 had “mysteriously” come around to the Chinese way of thinking, supporting the new repeal. The organization’s SARS “team leader” Julie Hall told the Times, “We have to keep an open mind. We may not eat dogs or cats, but we do eat raw oysters. We just shouldn’t pass judgment.”

The World Health Organization’s SARS leader literally said “we shouldn’t pass judgment” on the behavior that causes SARS. That’s like an oncologist refusing to pass judgment on smoking. It’s malpractice soaked in racial whataboutism (“Whites eat crazy things too!”).

By 2007, with the WHO no longer “passing judgment” and with the wet-market ban long gone, Reuters reported that “exotic wildlife and squalor have returned to the Qingping market, making health officials worried that another killer virus could emerge. Traditional wet markets still account for the bulk of fresh food sales in China, where diners hope exotic meats will bring good fortune.” Taiwanese health official Li Jib-heng direly predicted that “a new disease could emerge from close contact with sick wild animals.”

Even some Chinese officials were willing to publicly voice their concerns:

“It seems that some people are determined to start eating civet cats again since no new SARS cases have been reported over the past two years in Guangdong Province. It’s a very dangerous sign,” said Huang Fei, deputy director of the Guangdong Health Department. (‘China Daily,’ 2/14/07)

That same year, Guo-ping Zhao of the Chinese National Human Genome Center in Shanghai unequivocally stated in a paper for the Royal Society that a “ban on wild-game animal markets” would practically guarantee “no further naturally acquired human cases.”

The Chinese knew a ban would work, but they allowed the markets to thrive.

In 2013, Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post disclosed that a new Chinese zoonotic pandemic was likely: “Scientists warn of more serious disease threats than SARS.”

A survey that year by Beijing’s Horizon Research Consultancy Group showed that in Guangzhou, 83.3% of residents ate exotic animals.

The Chinese people were living in stubborn, arrogant denial, and the WHO had fallen silent because only racists “pass judgment” on Chinese zoonotic practices.

And now we have COVID-19, which has disrupted the entire world. One-third of the earth’s population is under some sort of lockdown. Livelihoods are ruined, economies destroyed, hundreds of thousands are ill and tens of thousands are dead. And the Chinese government, the Chinese diaspora, the political left, and the media want you to forget how COVID grew from the willful failure of China to learn the lessons of SARS.

So let’s not forget.

Remember that COVID-19, like SARS, began because of specifically Chinese customs, practices, and fetishes.

Remember that during and after the SARS outbreak, the Chinese knew that the wet markets were a danger, yet they were allowed to prosper.

Remember that experts predicted that a bigger, badder SARS would eventually be born from the wet markets. COVID-19 is the most predictable calamity in modern history.

And remember that a ban on Chinese wet markets would have prevented COVID-19. This was the most preventable calamity in modern history.

If we allow anything—fear of “racism,” hatred of Trump, lucrative Chinese business dealings—to get in the way of halting those wet markets for good this time, it’s a certainty that eventually we’ll see an even worse pandemic. There can be no soft feelings here, no sensitivity, no diplomacy. The Chinese must be cajoled, shamed, ridiculed, banned, and threatened until they stop risking the lives of every human on earth because they love eating things that shouldn’t be eaten.

The Chinese don’t deserve hugs; they’re lucky that most of us are civilized enough to not take violent revenge for what they’ve wrought. They should count their blessings that they can still walk among us unmolested. But they shouldn’t mistake our civility for forgiveness.

They have the power to shut the sky…and to strike the earth with every kind of plague as often as they wish. I’m not a religious man, but that line from Revelation seems appropriate. The Chinese have shut the world with their latest plague.

We need to make sure it’s their last.