October 14, 2020

Source: Bigstock

Establishment voices are finally, grudgingly admitting that murders and shootings are up spectacularly in 2020. But the reasons, they all agree, are immensely complicated and rather boring.

Perhaps, they muse, it has something to do with lockdowns? Or there could be any number of other subtly interacting factors. Who can tell? In any case, this mysterious rise in violence is beyond the comprehension, much less the control, of politicians. For example, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight headlined:

Trump Doesn’t Know Why Crime Rises or Falls. Neither Does Biden. Or Any Other Politician.

…We don’t actually know why crime went up this year. To be fair, we don’t truly know why crime goes up…well, ever. Nor do we know how to make it go down in the long term.

So there’s no reason to consider the sudden rise in slaughter in the cities when casting your vote this fall. Crime isn’t something immediately threatening like climate change where voting matters. Instead, the rise and fall of crime is a vast, mysterious process, reminiscent of continental drift in its inevitability, which public policy and media opinion couldn’t possibly affect. Indeed, wouldn’t you rather read about some outrageous tweet by Trump than about this intensely tedious giant outbreak of gunfire?

Seriously, the current shooting spree in our cities is one of the simplest, most flagrantly obvious phenomena in the history of the social sciences.

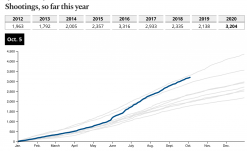

Consider this Chicago Tribune graph of shootings (i.e., number of people killed or wounded by bullets) in the Windy City:

Despite the weirdness of the coronavirus lockdowns that began in March, 2020 had been a pretty normal year for shootings in Chicago up through late May. Yet notice the sudden kink after Memorial Day in the blue line representing the total number of those shot so far this year. Over a single week at the end of May, Chicago shifted to a new, more violent slope.

Up through May 26, 2020, Chicago had seen 15 percent more shooting victims year-to-date than in 2019. But from May 27 through Oct. 5, shootings were up a stunning 74 percent over 2019.

Did anything happen in late May that encouraged criminals and discouraged cops? The data journalists appear stumped when they try to think back that far. But, as you may recall (it was in the news at the time), George Floyd died in police custody on May 25, and three days later the Democratic mayor of Minneapolis let rioters burn down a police station. From there, looting and rioting spread nationwide as the press and universities extolled the Mostly Peaceful Protesters.

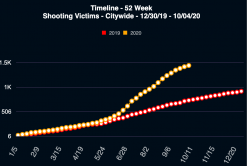

Similarly, here’s the NYPD’s graph of shooting victims in New York City with 2019 in red and 2020 in yellow:

Once again, 2020 was running strangely similar to 2019 despite the severe death toll NYC had absorbed in early April from the pandemic.

New York City, which has probably been the best policed big city in America in this century, did not see a rise in shootings as fast as Chicago did. But then in the first week of June 2020, gunplay ramped up and subsequently exploded in the second week of the month, the time of Floyd’s jaw-dropping funeral, with 72 victims versus 14 in the same week of 2019.

Through the end of May, 2020 shootings had been up 18 percent over 2019 in New York City. But in June through September, the number of killed or wounded has been an insane 156 percent higher than last year.

National trends have been similar to Chicago and New York. According to Wikipedia’s list of mass shooting incidents (which it defines as four or more wounded or killed), the number of people struck in mass shootings was up 14 percent over last year through the end of May. But in June through September, the number of victims of mass shootings grew by 61 percent from 1,005 in 2019 to 1,621 in the Summer of George.

One bit of good news has been that the mass shooters’ aim has been worse in 2020 than in 2019, with a higher ratio of wounded to killed. One reason is because highly lethal school and church mass shootings have declined from ten at this point in 2019 to only two this year, no doubt in part because schools and churches have so often been closed due to the virus.

Another cause is because even more than in 2019 when blacks, at 13.4 percent of the population, accounted for 55.9 percent of all murder offenders in the recently released FBI statistics, blacks appear to have been responsible for most of the mass shootings during the Summer of George.

(By the way, the black share of total murders in 2019, 56 percent, is roughly double the black share of people killed by the police, which is estimated to be from 1/4 to 1/3. That two-to-one ratio certainly offers a useful perspective on this year’s media obsession with police killings of blacks, but you aren’t supposed to know about it.)

There’s a telltale Pareto ratio that can help you discern between the two types of mass shootings. If you see a toll such as eight dead and two wounded, the mass shooter was likely a nonblack monster wanting his fifteen minutes of infamy. In contrast, a much more common mass-shooting outcome like two dead and eight wounded suggests the shooter was a black guy angry at somebody who dissed him and, at the moment, didn’t care how many bystanders at the block party he winged trying to kill him.

Thus, judging from 2020’s high wounded-to-killed ratio, mass shootings by blacks appear to be way up this year.

Total homicide counts (using any weapon) have risen as well. Writing in The New York Times in late September, Jeff Asher reported:

Over all, in 59 cities with murder data available through at least July this year, murder is up 28 percent relative to the matching time frame in 2019.

That’s up 28 percent year-to-date, so the increase in murders during just this summer’s Racial Reckoning is likely considerably higher.

And a new Washington Post analysis found that while crime in July was down in majority-white neighborhoods,

In majority-Black neighborhoods, the rate of violence remained relatively steady while stay-at-home orders were in effect, but rose dramatically after orders were lifted, peaking at 133 crimes per 100,000 residents in July, the highest level in the past three years.

The Post is trying to spin this strong evidence for a “Minneapolis Effect” as having something to do instead with coronavirus-deniers letting blacks out of lockdown. (What are we supposed to do, keep black neighborhoods under house arrest forever?)

But in reality, it was the Floyd Frenzy that made violence go up so much. An analysis of crime trends across twenty cities by criminologist Richard Rosenfeld of the Council on Criminal Justice found the usual pattern of Memorial Day being the inflection point: The timing of the murder spurt matches up closely with the Floyd Fury. Nothing much was different about homicide rates in 2020 until after Memorial Day:

The model estimated a structural break near the end of May 2020, after which the homicide rate increased by 37% through the end of June.

Rosenfeld reported that aggravated assaults (those committed with a deadly weapon or that otherwise threaten serious bodily injury) rose as well at the same moment:

The model estimated a structural break in the series near the end of May 2020. (Recall that the structural break model adjusts the estimate for seasonal effects.) The aggravated assault rate rose by 35% from late May through the end of June 2020.

Rosenfeld was a prominent skeptic of the “Ferguson Effect”—the 22.9 percent increase in murders from 2014 to 2016 that followed the rise of Black Lives Matter after the police shooting in Ferguson, Mo., of Michael Brown in August 2014—until the data for its existence became overwhelming. Rosenfeld now writes:

it is instructive to compare the recent upturn with the increase that occurred five years ago in the midst of a similar period of widespread protest against police violence. Homicide and nonfatal violent crime increased in 2015 and 2016 in the aftermath of protests against police brutality in Ferguson, MO, Baltimore, Chicago, and elsewhere around the country.

Rosenfeld offers two versions of the Ferguson (and now Minneapolis) Effect:

The first connects the violence to “de-policing,” a pullback in law enforcement. The second essentially turns this explanation on its head and connects the violence to “de-legitimizing,” positing that communities, disadvantaged communities of color in particular, drew even further away from the police due to breached trust and lost confidence. As a result of diminished police legitimacy, fewer people reported crimes to the police or cooperated in investigations, and more engaged in street justice to settle disputes….

But I think I can unite his two explanations into one fundamental question: Who are perceived to be the good guys and who the bad guys—the police or the criminals?

From Ferguson to the election of Donald Trump (which followed the July 2016 BLM terrorist shooting of fourteen Dallas policemen), leading elements of the Establishment joined with the underclass to proclaim a Narrative in which every cop is a criminal and all the sinners saints.

The media temporarily quieted down about BLM after November 2016. Under the anti-crime Trump Administration, the national murder rate edged downward. But by early May 2020, the press had decided that hyping prowler Ahmaud Arbery’s death would be helpful in bringing down Trump. Then, when fentanyl abuser George Floyd expired in police custody on Memorial Day, the press was primed to push stir-crazy young people into the streets for the “racial reckoning.”

To be clear, most of the incremental shootings have not taken place during the Mostly Peaceful Protests. Instead, the hosannas of praise devoted to lowlifes like Arbery, Floyd, Rayshard Brooks, and Jacob Blake have rewritten the basic script of civil society about who are the good guys and who are the bad guys.

Perhaps my most important insight is that America is steadily regressing toward a 6-year-old boy’s way of thinking. Worse, we are increasingly assuming that you can tell the good guys from the bad guys by the color of their skin.

Anglo-American progressives once prided themselves that they distinguished the goodness or badness of individuals by consideration of their behavior under rule of law. In the 1861 words of British legal theorist Henry James Sumner Maine: “…the movement of the progressive societies has hitherto been a movement from Status to Contract,” with “status” traditionally having been largely defined by who your ancestors were (noble, commoner, slave, untouchable, or so forth).

But now we are devolving back toward lowbrow identity-based sentimentalism: For instance, you are now supposed to be able to tell at a glance that these crooks resisting arrest are really the good guys, despite their behavior, because they are black.

Not surprisingly, the police have responded to the Establishment blood-libeling them for doing their jobs by not doing their jobs. The police are inherently political (as their name suggests). Cops do what the politicians back them in doing. If the current politicians aren’t in the mood to defend the police for enforcing the laws that other politicians passed in the past, the cops will go get another doughnut.

Conversely, the criminal element has responded to the national media’s massive show of concern and support by feeling even more entitled to do whatever they want, such as shoot up funerals and BBQs.

You might think that this summer’s shooting rampages in black neighborhoods are good evidence that the press should be more prudent about lecturing blacks that they ought to be enraged. But blacks are ever more America’s sacred cows, so practically nobody dares point out the obvious truths about what’s really going on in 2020.

Fortunately, interracial homicide is not all that common in the United States. While there has apparently been a disturbing trend toward some blacks lashing out with random racism toward whites this year, such as the recent punching of venerable comedy actor Rick Moranis while he was walking down the street, in general the races have learned to keep out of each other’s hair.

In 2019, among murders in which perpetrators were charged and the race of victims recorded, in 84 percent of murders both offender and victim were members of the same racial group, as broadly defined by the FBI using only three categories: blacks, whites (including 93 percent of Hispanics), and Others (Asians, American Indians, Pacific Islanders, etc.).

Of those 16 percent of all murders that were interracial, blacks were the offenders in 62 percent as measured by the FBI.

That’s a large percentage for a group only slightly more than one-eighth of the population. But then again, blacks also comprised 49 percent of intraracial murder offenders. The chief American crime problem is less that blacks kill a lot of nonblacks in particular than that blacks kill a lot of human beings in general.

But while murder victims, mostly black, pay the highest price for the high rate of black murderousness, and black bystanders pay substantial prices for having to live around the homicidal, we all pay indirect costs: such as having “bad” neighborhoods and expensive “good” neighborhoods, a costly criminal justice system, periodic orgies of white guilt, riots, the moral rot caused by the need to not tell the truth about black murders, and so forth.

Obviously, the best solution would be for blacks to behave better, but not even Donald Trump dares call for that win-win solution. (In his better moments, Barack Obama would occasionally orate vaguely in that general direction, but in the crisis of 2014–2016 he couldn’t stop himself from rashly stoking the black rage that got so many policemen shot in Dallas.)

It remains extremely reckless for American elites to lecture blacks on how they ought to be even angrier than they already are. In 2019, blacks were 8.2 times more likely per capita to be murder offenders than were nonblacks (which, remarkably, is even worse than the male vs. female murder gap of 7.6 times).

With all the media incitement of racial rage still going on, God only knows what that ratio will turn out to be this year.

And what about the future? By unleashing crime, the comparable liberal ideologies of the 1960s did damage to our cities that took generations to repair. Is it too much to ask that we have an honest public discussion of what the Establishment is inflicting upon urban America?