January 20, 2015

Source: Shutterstock

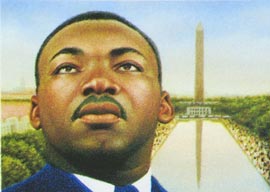

On Martin Luther King Day, 2015, how stand race relations in America?

“Selma,” a film focused on the police clubbing of civil rights marchers led by Dr. King at Selma bridge in March of 1965, is being denounced by Democrats as a cinematic slander against the president who passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In the movie, King is portrayed as decisive and heroic, LBJ as devious and dilatory. And no member of the “Selma” cast has been nominated for an Academy Award. All 20 of the actors and actresses nominated are white.

Hollywood is like the Rocky Mountains, says Rev. Al Sharpton, the higher up you go the whiter it gets.

Even before the “Selma” dustup, the hacking of Sony Pictures had unearthed emails between studio chief Amy Pascal and producer Scott Rudin yukking it up over President Obama’s reputed preference for films like “Django Unchained,” “12 Years a Slave” and “The Butler.”

“Racism in Hollywood!” ran the headlines.

Pascal went to Rev. Sharpton to seek absolution, which could prove expensive. Following a 90-minute meeting, Al tweeted that he had had a “very pointed and blunt exchange” with Pascal, that her emails reveal a “cultural blindness,” that Hollywood has to change, and that Pascal has “committed to this.”

These cultural-social spats—LBJ loyalists vs. the “Selma” folks, Sharpton vs. Hollywood—are tiffs within the liberal encampment, and matters of amusement in Middle America.

More serious have been the months-long protests against police, following the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner on Staten Island, some of which have featured chants like, “What do we want? Dead Cops!”

The protests climaxed with the execution in Bedford-Stuyvesant of two NYPD cops by a career criminal taking revenge for Garner and Brown.

Race relations today seem in some ways more poisonous than in 1965, when there were vast deposits of goodwill and LBJ pushed through the Voting Rights Act easily, 77-19 in the Senate and 328-74 in the House. Only two Republican Senators voted against the VRA.

But not a week after LBJ signed the Voting Rights Act, the Watts section of Los Angeles exploded in one of the worst race riots in U.S. history. After seven days of pillage and arson, there were 34 dead, 1,000 injured, 3,000 arrested, and a thousand buildings damaged or destroyed.

The era of marching for civil rights was over and the era of Black Power, with Stokely Carmichael, Rap Brown and The Black Panthers eclipsing King, had begun.

In July 1967, there were riots in Newark and Detroit that rivaled Watts in destruction. After Dr. King’s murder in Memphis in April of 1968, riots broke out in 100 more cities, including Washington, D.C.

By Oct. 1, the nominee of the Democratic Party, civil rights champion Hubert Humphrey, stood at 28 percent in the Gallup poll, only 7 points ahead of Gov. George Wallace.

Though Nixon won narrowly, the Great Society endured.

And in the half-century since, trillions have been spent on food stamps, housing subsidies, Head Start, student loans, Pell Grants, welfare, Medicaid, Earned Income Tax Credits and other programs.

How did it all work out?

Undeniably, the civil right laws succeeded. Discrimination in hotels and restaurants is nonexistent. African-Americans voted in 2012 in higher percentages than white Americans. There are more black public officials in Mississippi than in any other state. In sports, entertainment, journalism, government, medicine, business, politics, and the arts, blacks may be found everywhere.

Yet the pathology of the old urban ghetto has not disappeared. In some ways, it has gotten much worse. Crime in the black community is still seven times what it is in the white community.