May 11, 2021

I hadn’t planned to buy the new authorized biography of novelist Philip Roth, author of Portnoy’s Complaint and American Pastoral, because I am at best a lazy admirer of Roth, having read only a handful of books by the indefatigable novelist who died in 2017 at 85. But when I saw it on the bookstore shelf, I grabbed it because the biography is being permanently taken out of print by its own publisher, Norton, for #MeToo reasons.

Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth is already unavailable on Kindle. In the coming digital dark age, it may be prudent to have some physical books stashed in your basement so you can at least say, “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.”

Indeed, the only thing unexpected about the cancellation of the biography of Roth, a contender, alongside his friend and rival John Updike, for the title of The Great American Horndog, is that the justification wasn’t Roth’s own history of philandering but his biographer’s.

Now that Bailey has a best-seller, several women have come forward to announce that they had sex with their former eighth-grade English teacher, who had groomed them by assigning Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita to the class.

This would be shocking, except that the accusers all admit the encounters were years later when they were adults.

One thing you will learn from studying the lives of leading authors is that more than a few intelligent women can’t resist a literary genius.

Not that Bailey is an author in the class of Roth, much less Updike, but he is a lively writer. His 898-page authorized biography is a more fun read than the similarly massive new authorized biography of Tom Stoppard that I reviewed recently. Besides the difference in biographers, the gracious Stoppard is alive and still working with many famous people who would prefer not to be gossiped about, while the vengeful Roth is settling scores from the grave. Moreover, Stoppard is boyish while Roth was adolescent.

Roth was a cocky son-of-a-gun. Hence, he is an amusing character to read about, a Henry James-like mandarin man of letters with the wisecracking personality of Bugs Bunny.

And, despite all the wisdom about human nature he portrayed in his 27 largely autobiographical novels, in real life Roth displayed some of the entertaining self-destructiveness of Daffy Duck. Despite all the estimable women who threw themselves at Roth over his half-century-long reign near the top of American literature, the two women he chose to marry turned out to be disasters for him.

The second, actress Claire Bloom, even wrote a best-seller about a what a rotten guy he was. (One of her more memorable complaints was that despite his bad-boy reputation, Roth was a workaholic bore: He wrote his books for eight hours straight every day and then he read serious literature for four hours every evening.)

Reviewers of Bloom’s Leaving a Doll’s House labeled him a misogynist, although as Roth and his idol, the five-times-married Saul Bellow, agreed, their problems with women could be more charitably said to stem from “an all but helpless susceptibility.”

Roth also had his idealistic side: A patriotic Jewish-American liberal who took free speech seriously, he was probably second only to Stoppard among English-language creative writers in introducing Westerners to anti-Soviet Eastern European dissident authors, such as Milan Kundera.

Roth was a loyal ethnic Jew, but he didn’t consider his people to be sacred cows too fragile for satire. And he didn’t value Israel over his native America, which in Roth’s view had been very good for the Jews. He outraged future Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert by telling him in the late 1980s that few American Jews would ever make aliyah to Israel because, “There is a Zion, and it’s called America.”

Most of the last cohort of heavyweight American novelists, such as Tom Wolfe, Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy, Don DeLillo, and Thomas Pynchon, were born between 1930 and 1937. Roth’s explanation for this was that his was the last generation who truly cared about books because they grew up before television.

Updike (born in Reading, Pa., in 1932) and Roth (born a year and a day later in Newark, N.J.) had enough in common that they can be readily compared in the way that it’s fun to contrast George Orwell and Evelyn Waugh (both born in 1903).

Since they were both enormously prolific, I find it interesting to study their career arcs.

Both published acclaimed works of fiction in their 20s: Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus, which satirized postwar Jewish affluence, and Updike’s Rabbit, Run, in which a former high school jock with a two-digit IQ (but, for unexplained reasons, the supreme perceptive consciousness of John Updike) repeatedly makes bad decisions that bring trouble for everybody around him. Yet, Rabbit keeps turning out okay because, hey, America is more of a comedy than a tragedy.

Both followed up with worthy books that solidified their literary reputations more than their net worths. Then in 1968, Updike published his dirty best-seller Couples. Roth followed the next year with his dirty mega-seller Portnoy’s Complaint about a nice Jewish boy who loves the shiksas too much to please his parents. If white guilt is worrying that your ancestors were too ethnocentric, Jewish guilt is worrying that you aren’t ethnocentric enough for your ancestors.

In the early 1970s, Roth published some lousy books, such as his strident Richard Nixon parody Our Gang, while Updike pulled ahead in repute.

Updike took a break from his usual subject matter of suburban adultery to visit Africa and then spent a year in the library researching the continent for The Coup, an astonishing 1978 novel about an American-hating Marxist-Islamist dictator who happens to have the prose style of John Updike. In it, at the depth of the post-Vietnam slump, Updike prophesied that American capitalism would win the Cold War.

Although it was a best-seller at the time, The Coup is utterly forgotten today, even though it includes an uncannily accurate foretelling of Barack Obama’s parents’ brief marriage.

Updike then went back to Middle America in his 1981 career peak Rabbit Is Rich. It’s the energy crisis of 1979 and America is running out of gas…except that our seemingly feckless hero has inherited his father-in-law’s auto dealership, and not even Rabbit can screw up making money off Toyotas. And besides, the author wasn’t suffering an energy crisis in his late 40s. As he wrote in 1990: “I was full of beans, really, looking back on it from my present relatively beanless condition.”

At some point after that, Updike appears to have decided that he was over-the-hill and thus he wasn’t going to work as hard on any single book anymore. He could of course still simply exude gorgeous Nabokovian prose for four hours per day, but he wasn’t going to invest the effort he had put into his big books written in his mid-40s. Moreover, Updike was more a lyric writer, which, as Kundera pointed out in The Lyrical Age, is very much a youthful skill.

Updike, who wrote a famous article as a young man about 42-year-old Ted Williams homering in his last at-bat, had always had an athlete’s awareness of the inevitability of fading powers. Rabbit, for instance, peaked in high school. Updike was a close student of baseball statistics, so he likely wouldn’t have been surprised by Bill James’ finding that baseball stars peak at 27. Updike’s later books rather cheerfully chart his decline as if he were pleased to see his predictions fulfilled.

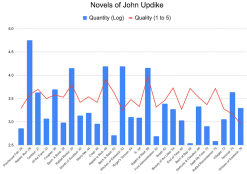

Thus, Updike’s popularity fell off with age:

Above is a graph I made from the Goodreads website of readers’ ratings of Updike’s novels (the number after the novels’ titles are his age when they were published). The blue bar represents a log scale of how many ratings the book has gotten, and the red line is the average rating on a 1–5 scale. (Note that this graph does not depict sales or critics’ reviews from the time of publication, but instead is what self-selected 21st-century readers have to say.) Updike’s most often-rated novels are the Rabbit series and The Witches of Eastwick, which was made into a star-packed movie. His highest-rated novels are Rabbit Is Rich and Rabbit at Rest.

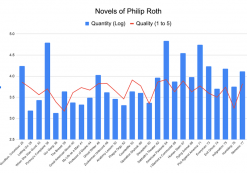

Although Roth was also a baseball fan, he didn’t seem to foresee the impending inevitability of his decline as vividly as Updike did. As a social novelist with an elegant but not exquisite prose style, his knowledge of society only deepened with age.

Roth kept plugging away and really hit his stride in his 60s. His most admired novel may be 1997’s American Pastoral, in which a Jewish high school jock legend named Swede Levov, Roth’s tragic version of Rabbit Angstrom, has his beautiful life destroyed by the America of the ’60s.

As you can see, Roth’s most popular books came early and late in his career, with dips in quality only after Portnoy and, modestly, in his 70s.

This is not to say that the collective judgment of the peanut gallery at Goodreads is always correct. Still, it tends to accord with what I can recall. Roth was most famous early and late, while Updike was a bigger name in the middle years.

At this point, it looks as if Roth, due to his strong finish, wound up perhaps the greater novelist (although such judgments usually shift over time). On the other hand, Updike exceeded Roth as a short-story writer, critic, and poet.

So, I declare them tied.