April 25, 2011

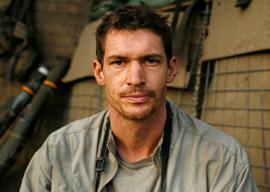

Tim Hetherington

When journalists die in some foreign field, they die for you. Without them, your knowledge of the world in which you live would come from government spokesmen, corporate flacks, and pundits who don”t leave their television studios or think tanks. Two frontline photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, have just been killed in Libya. Hetherington was forty and Hondros forty-one. Both were first-class journalists who went by sea from Benghazi to the frontlines in Misrata. After another of the endless skirmishes between Colonel Gaddafi’s army and the rebels, a rocket-propelled grenade exploded in their midst. It killed both men and severely wounded their colleagues Guy Martin and Michael Christopher Brown.

The Oxford-educated Hetherington had a brilliant career, now cut lamentably short. His film on Afghanistan, Restrepo, earned an Oscar nomination last year and the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Festival. He won the World Press Photo of the Year Award for 2007 and had also taken a prize named for another photographer killed in the line of duty, the Rory Peck Award.

Hondros, who worked in Kosovo and Afghanistan among other wars, was responsible for a startling series of photographs of a family that failed to stop abruptly at an American checkpoint in Iraq. US soldiers shot the parents dead and wounded one of their five children in the backseat. The armchair warriors would say it’s an everyday occurrence in war, as if that provided absolution. Hondros explained later:

Almost every soldier in Iraq has been involved in some sort of incident like that or another, I would say. Their attitude about it was grim, but it wasn”t the end of their world. It was, “Well, kind of wished they”d stopped. We fired warning shots. Damn, I don”t know why the hell they didn”t stop. What”re you doing later, you want to play Nintendo? Okay.” Just a day’s work for them.

Such testimony makes it all the more difficult to believe that sending in the Marines will solve all problems everywhere.

Photographers and the people who record the news on film or video cameras take more hits in conflict than mere scribes such as myself, who enjoy the luxury (or the excuse) of staying a little back from the fighting in order to observe it better. The photographer and camera operator must go to the coalface to record the sights and sounds of combat and make warfare’s impact visible. The toll of fallen photographers lengthens each month. None of those I have known or worked with could be called “war junkies.” Their vocation was to bring home the bloodshed so blithely endorsed by people in the imperial centers without whose weapons and financing most wars could not take place. One of the finest photojournalists of the twentieth century, the proud Welsh patriot Philip Jones Griffiths, once criticized some of his colleagues for making profits out of America’s war in Vietnam. They countered by asking him what he was doing in Vietnam, from where he produced one of the best books to come out of that conflict, Vietnam, Inc. He answered, and I paraphrase from memory, “I was gathering evidence for the next Nuremberg Trials.”