June 05, 2020

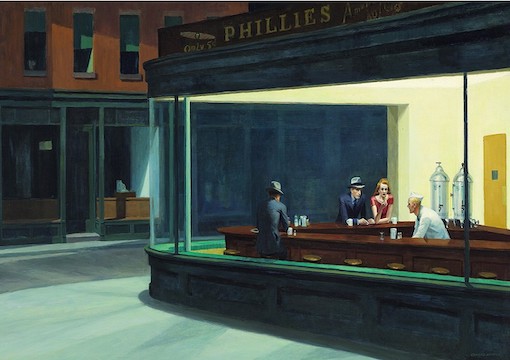

Nighthawks, Edward Hopper

Solitude is a blissful disengagement from the horrors of modern-day life, even if forced upon us by a government lockdown. The trouble with the present situation is the idiot box. The enforced solitude would be a blessing—it tends to breed spirituality—but for the escapism of television. The absolute rubbish, the vulgarity and violence that the networks put out nowadays and call entertainment, is far more dangerous than the virus we’re isolating against.

But this is about solitude, so I’ll skip the Hollywood horrors. We tend to derive as much good from time spent alone as we do from interpersonal relationships. It can, of course, have terrible effects, as in Conrad’s Nostromo, where a character expires after being stranded on a deserted island. He was said to have died of solitude, something I can understand. How would you like to be stranded on an island with, say, the Goldberg woman who writes a column for The New York Times and thinks everyone white or Christian is a Nazi? (Perish the thought.)

The Romantic poets praised solitude and lone ramblings, while wounded soldiers during World War I looked forward to the peace that comes when away from noise. Solitary pursuits such as fishing, reading, even smoking are guaranteed to satisfy because one indulges in them alone. And solitary confinement in prison surely is preferable to sharing a tiny cell with some ruffian going through his daily libations. Yet solitary confinement is considered to be a cruel and inhuman punishment by busybodies.

We’ve known since Aristotle that human beings are social animals and that no war, plague, or catastrophe will ever change that. (Well, Oprah Winfrey’s programs could do it in a jiffy, but there I go again.) Solitary lives are said to damage our physical health as much as smoking, but I don’t buy it. During normal times I go out almost every night of the week; I drink and smoke and stay up late, pursue women if possible, and live what’s called a social life. The past three months have given me time to think a bit, and I’ve come to the conclusion that the last intelligent thing I heard at a party was that the purity of the air in Palm Beach is due to the fact that the people who live there never open their windows. But the past three months have been eye-openers. I was stuck in my Swiss chalet high up in the mountains with some of the worst people, as far as manners are concerned, this side of Noo Yawk: mostly rich Eurotrash and Persian Gulf lowlife women abusers. I sent away my staff under full pay and remained alone with my wife and son. And was never happier. Mind you, the two of them cooked and cleaned up, but I hit the books while they beavered away. No hangovers, no regrets about wasted time, no embarrassment at stupidities uttered when under the influence. A new Taki was born.

They say that people are social animals and need the company of others, which in the present society we live in is obviously true. Which explains the nonstop blabber of utter rubbish one hears in the street nowadays. When I was a child—during the Homo neanderthalensis period 1.5 million years ago—I was told time and again not to speak unless I had something of value to dispense. Well, that was then, when people still had manners and women did not go on television and talk about the cream they use to shave their intimate parts.

What is definite is that solitude affects the brain in a positive way. Creativity and solitude are as symbiotic as, say, Nancy Pelosi and Adam Schiff are to mendacity. No artist better captured the condition of solitude, and of course loneliness, than the great American Edward Hopper. He created a suspended narrative of solitude and loneliness with Nighthawks, his dramatic masterpiece of a New York late-night diner. Hopper was what was known as an American gentleman, an artist who distinguished himself from his peers back at a time when total phonies like Warhol and Basquiat had not as yet surfaced from the gutters. Solitude and unnerving stillness were Hopper’s trademarks.

Actually, the enforced solitude was like being back in the ’50s again. A tidier, less frantic time, with less noise overhead, less traffic, and no toe-curling embarrassing chitchat in the streets. I heard less F-words than there are intellectuals in Hollywood, but then the cows that I live next to at my Gstaad farm are known for having better manners than most visitors, especially the Johnnys-come-lately. What makes me wonder now that we’re getting back on track—alas—is how many of the people who write for social media or appear on the idiot box knew how to spell the word “epidemiology” before they began to enlighten us with their rubbish. Mind you, this isolation that I praise has been bought at too great a price. The Donald, a man who doesn’t like to be alone, should have never shut the place down. He will have lots of time to regret it.