April 26, 2021

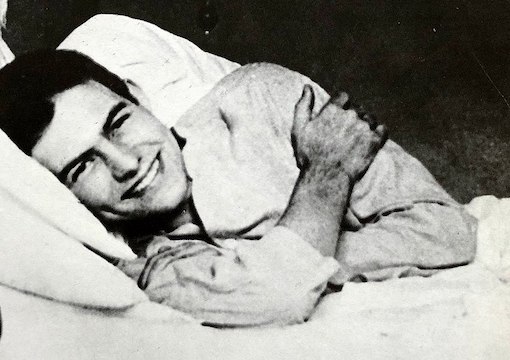

Ernest Hemingway

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Writing in the London Spectator quite a long time ago—I’ve been a columnist there since 1977—I listed some great Americans, among them General Robert E. Lee, Charles Lindbergh, and Ernest Hemingway. Needless to say, if one were to mention some of these names today in an American publication, or dare bring them up on a news program, all hell would break loose and the writer would instantly become a nonperson. The left-dominated, nihilist pop culture of today and the academic establishment, supported by the laughable “mainstream media,” have turned this once-great nation into one of identity politics and grievances. Common sense has been replaced by crazed theories about subconscious prejudices, and promoting social justice is the frenzied order of the day.

Hence I was pleasantly surprised when PBS announced that it was showing a six-hour Ken Burns and Lynn Novick documentary on Papa Hemingway over three nights, an event that predictably the degenerate New York Times called “subversive.” Burns and Novick have done in-depth series on baseball and Vietnam, not to mention the Civil War, so I wasn’t worried even after the degenerate old bag had asked, “Why now?” I say why not now, when masculinity, patriotism, courage, and beautiful, graceful writing are all under attack by effete, nerdy, asexual freaks posing as gamekeepers of political correctness.

Hemingway was to American stripped-down prose what he claimed Mark Twain was to the American novel: the father of it. Not even the degenerates of today can deny that he invented the style of clean, lucid prose, to go along with his creation of a virile swagger, one that first drew me to him. His macho bluster is looked down upon in today’s feminized world, but he was as brave as they come, having been seriously wounded at age 18 and come under fire time and again in both world wars and during the Spanish civil conflict.

I first saw him swaggering down Fifth Avenue when home for the holidays from boarding school in 1954. I followed him and to my delight he entered El Borracho, a restaurant off Fifth Avenue that my parents used to regularly take me to. It was nearly empty and he sat at the bar. I approached, introduced myself as a great fan of his, named my prep school, and was offered drinks by him. I had three whiskey sours and got completely soused. The barman hadn’t dared deny him despite me being underage. We discussed “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and The Sun Also Rises. Then he suddenly asked for the bill, tapped me on the shoulder, and was gone. I walked up Fifth Avenue where I lived, and I remember my mother’s shock at me being drunk at three in the afternoon. She was no fan of America, its familiarities, and its manners. The next day I went to Dunhill Tailors and ordered a brown tweed suit just like the one Papa was wearing. (It was very itchy.) Three days later it was all over. The New York Post exposed my NBF as a total phony. The real Papa was in Venice. To say I was crestfallen would be a gross understatement.

The new documentary has no gauzy, nostalgic patina tinting the text. But it deftly illustrates to the viewer how literature was and is still shaped by Hemingway’s ideas of clarity and brevity. He stripped away the florid style of, say, Henry James and Edith Wharton, and instilled his macho manliness with the power of his pen. His drumbeat rhythms and lyric beauty of his style turned millions of readers into little Hemingways, copying his style in conversation and in writing. Lastly, it established the enduring myth of the man.

Reading last month’s Chronicles, I noticed the objections of certain readers over true versus false conservatism, and the editors’ response. Papa was no conservative in its present form, but manliness, truth, courage, grace in the face of danger, patriotism, and love of country are conservative traits, and he had them all. Reevaluating icons is now the order of the day, and Papa Hemingway is everything the left hates and fears. That alone in my book makes him a great conservative. Like Norman Mailer, Irwin Shaw, and James Jones, Papa had seen action in war, and that separates him from the effete creatures who now pass as writers. He was brainy yet brawny, a far cry from, say, Proust.

Charles Scribner III, the grandson of Papa’s publisher, said F. Scott Fitzgerald was Strauss. Hemingway, by contrast, was Stravinsky. His stark, staccato prose, its tonality, was modernity itself. I remember well sitting in my aunt’s Athenian garden reading his obituaries back in 1961. Never have I wanted anything more in life than to become a writer like him—an unfulfilled wish by a mile, but a goal that shaped my life. Papa never flinched in the face of danger, chased beautiful women, drank like a Karamazov, and took his lumps with complaint. His head traumas after numerous accidents are what did him in. I couldn’t watch the end, but I did. I hope that our present lot also watched and will try to stay safe from now on in their nappies.