October 09, 2020

Source: Bigstock

During my recent period of quarantine in England, I was surrounded in my study by piles of books that I have always intended to read before I die. Even this modest ambition is unlikely to be fulfilled, however, given their number, my life expectancy, and the rate at which I read them. It would require quite a number of breakthroughs in medicine for my ambition to be realistic.

Among the books was History of the Epidemic Spasmodic Cholera in Russia Including a Copious Account of the Disease Which Has Prevailed in India, and Which Has Travelled, Under That Name, From Asia Into Europe, by Bisset Hawkins, M.D., published in 1831. I cannot remember when, or where, I bought the book, or even whether at the time I had a particular reason for doing so; but I am glad that I did.

The book was a compilation from reports of others rather than the fruit of personal acquaintance with the disease, which at the time of writing had reached Moscow but not further west. But, wrote Dr. Hawkins:

It is possible, but happily not very probable, that this unwelcome stranger may make its appearance on our shores more speedily and more suddenly than we have reason to anticipate; and in such a contingency, however remote, it would be desirable that country magistrates, clergymen, and medical practitioners…should be enabled to possess the painful experience which has been acquired in other countries.

I seem to remember that once, not so very long ago, something rather similar was said in the United States about an epidemic then raging in Europe. I hesitate to quote Marx, of whom I am not an altogether unequivocal admirer, but he did say that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.

There is much else in the book that might stimulate reflection. For example, Dr. Hawkins says:

The public cannot be too earnestly cautioned against lending an eager ear to the imaginary cases which have been attempted to be fastened on their attention, and which will probably be abundantly supplied…in order to pamper a luxurious appetite for the terrible….

“A luxurious appetite for the terrible”: Who would assert that such a thing does not exist? We prefer a calamity to a minor misfortune, at least insofar as it affects others, because the latter are boring.

Dr. Hawkins is optimistic about the prospects:

No worse preparation can be made for the disease, in the event of its arrival, than a premature panic. Our Government has used every prudent precaution for the possible calamity, by Quarantine regulations directed against both persons and merchandise, by establishing a Board of Health, hospital ships, at the principal points. This timely foresight, combined with the greater degree of individual prosperity and competence, with the habits of neatness and cleanliness, and with the singular benevolence towards distress which characterize our country, may probably avert the evil….

The cholera arrived in Britain only a little later in the year of the book’s publication, and 32,000 people are thought to have died of it, the equivalent pro rata of about 160,000 today. Even in those days, the place where it made its first appearance in the country, Sunderland, was not known for the “neatness and cleanliness” of its population, there being no means to secure it.

Some things do not change:

In several parts of this work will be found fresh confirmation of a most important principle in state medicine [i.e., public health]: that the tendency to a fatal termination of disease increases in proportion to the poverty and ignorance of the individual.

This holds within a society, but it does not necessarily hold between societies: The relation of GDP per capita and death rate from COVID-19 is not a strong one, to put it mildly. However, there is (as far as I am aware) no society in which COVID-19 has killed a non-negligible number of people and in which the death rate has been higher among the rich than among the poor.

It is instructive to read the way in which doctors in 1831 treated the disease. They were convinced that they were doing good, when to the modern eye they appeared to have been hastening death. Of course, no proper scientifically conducted trials have been mounted to test their methods, and it is in the last degree improbable that they ever will be mounted, because undoubtedly effective treatments are known to work and a rationale for their methods was lacking, to say the least.

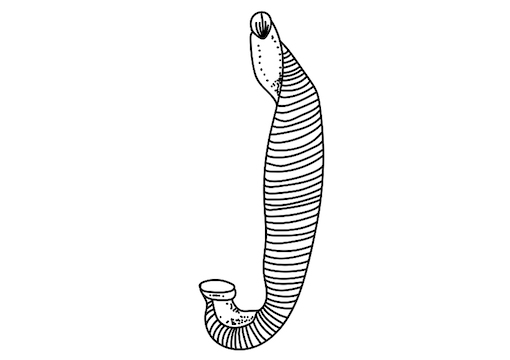

For example, they gave mercuric chloride to patients with cholera, a laxative with poisonous properties. They bled the patients, though frequently their veins were so collapsed that they could not easily do so, in which case they applied leeches to them in large quantities. The description is not for the fainthearted:

When the patient shrinks from pressure on the abdomen [presumably from the physician’s examining hand], leeches should be applied in considerable numbers, and particularly in the neighbourhood of the liver; and when the head is affected, they should be applied at the temples and base of the skull.

I cannot help but recall the satirical jingle about John Coakley Lettsom, a famous English physician of the 18th century:

When any sick to me apply, I physics, bleeds and sweats ’em,

If after that they choose to die, Why verily! I lets ’em.

The lesson, however, is that the doctors who treated their cholera patients in the way Dr. Hawkins describes were not stupid or wicked men, and yet they believed both absurdities and that they were doing good. Indeed, they were convinced of it: Their experience, they said, proved it to them. Dr. Hawkins quotes one of them to the effect that no patient survived without his treatment, but many did survive with it.

This loose manner of reasoning is far from expunged, and perhaps never will be expunged, from the human mind. All over the internet, for example, one may find people absolutely convinced of the efficacy of some nostrum or other in COVID-19, without any proof other than their conviction. It would do them good, perhaps, to read Dr. Hawkins. On the other hand, people (except for me) are rarely swayed by purely rational considerations.

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Embargo and Other Stories, Mirabeau Press.