October 30, 2013

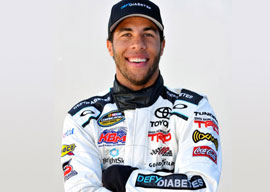

Darrell Wallace, Jr.

There was a fair amount of national media excitement this weekend over the news that Darrell Wallace, Jr. had won a NASCAR race.

As a Southern Californian, my attention span for auto racing has shrunk to the four seconds it takes a top fuel dragster at the Pomona Winternationals to roar 1,000 feet in a straight line. So I haven’t really been following as closely as I should all the drivers down in Dixie going around and around. And around. (And, I suspect, around some more.)

I’ve been especially lax about keeping up with NASCAR’s minor-league truck-racing circuit on which the 20-year-old Wallace triumphed Saturday. Nevertheless, his victory in Martinsville, Virginia was deemed major-league news because, you see, Wallace is a product of NASCAR’s nine-year-old Drive for Diversity program. He’s the first African American to win even this kind of third-tier NASCAR event since 1963.

Presumably, after this shattering of barriers and furnishing of a suitable role model, black drivers will flood NASCAR, just as Tiger Woods’s 1997 Masters victory led to all the black golf champions we see today.

(Oh, sorry, that didn’t happen as forecast.)

The news should raise the question: If it takes so much organized effort in the 21st century for a black to win a small-time NASCAR contest, how in the world did Wendell Scott triumph in a Grand National race a half-century ago, back before diversity awareness?

It’s a terrific story, one that was made into a 1977 biopic, Greased Lightning, with Richard Pryor playing Scott. (In real life, Scott looked more like a swarthy Gene Hackman.)

Like Junior Johnson (whom a young Jeff Bridges portrayed in The Last American Hero, a 1973 adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s famous 1965 Esquire article), Scott got his start bootlegging moonshine and trying to outrace the revenuers.

In 1952, a struggling racetrack in Danville, Virginia was looking for a gimmick to excite public interest. So the managers “asked the Danville police who the best Negro driver in town was. The police recommended the moonshine runner whom they had chased many times and caught only once.” The news brought a big crowd, including new black fans, to the racetrack. Scott contended for the lead, but over several laps his 1935 Ford comically disintegrated.

The 30-year-old novice then struggled for years to make it in a sport that functions as a sort of implicit ethnic-pride festival for Americans not allowed to hold ethnic-pride festivals, finally achieving sustained success in the 1960s.

I was too young to hear about Scott’s 1963 Jacksonville win, but I recall his name during my years as a car guy from 1967-1969. I was more into dragsters, such as the science-fiction-style top fuel and cartoon-like funny cars, than the more mundane-looking stock cars. But I was less ADD when I was an eight-year-old, so I followed all the circuits and can recall Wendell Scott’s name coming up near the top of the agate type columns of race results. He never won again after 1963, but impressively, Scott finished in the top ten overall for each year from 1966 through 1969.

As a boy, I tended to get Scott confused with Charley Pride, a black country and western singer who broke through in Nashville in 1967 and had six straight number-one country chart toppers in 1969-71. They were both Southern blacks making it in white Southern businesses.

That seemed to be the general pattern back then: the lifting of hard-and-fast racial lines meant that talent flowed into unexpected fields.