May 25, 2011

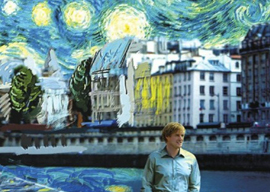

Owen Wilson

Gorgeous as it may look, contemporary Paris bores Gil. Instead, he’s fascinated that he’s walking the same streets as his 1920s idols. A favorable post-WWI exchange rate made Paris cheap for affluent Midwesterners such as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Cole Porter. Those artists weren”t starving. The title of Hemingway’s Parisian memoir, A Moveable Feast, can be read literally: A three-course dinner with wine cost $0.20 back then.

While Gil is out walking one midnight, an ancient Duesenberg limousine full of young flappers pulls up and carries him back in time to a 1927 Charleston dance party where Porter is pounding out on the piano his new song “Let’s Do It (Let’s Fall in Love).” Paul Johnson observed, “The keynote of the 1920s musical was joy, springing from an extraordinary exuberance in the delight of being alive and American.” Joy is the dominant emotion Woody conveys in his movie about an American in Paris.

Every midnight, Gil hops in the limo and meets more legends. Fitzgerald introduces Gil to Hemingway, who speaks only in oracular run-on sentences about courage and grace and manhood. Hemingway takes him to meet Gertrude Stein (a businesslike Kathy Bates), Picasso, and Matisse. The funniest cameo is Adrien Brody’s impression of surrealist Salvador Dali (or, as he refers to himself in the third person, “dah-LEEEE”). Brody plays the mannered Spaniard as a confident version of Manuel the Waiter from Fawlty Towers.

Cheap as Paris was for foreigners, how could modern Gil pay for all this high-class socializing with a wallet of credit cards and Euros? What could you bring from the present that would be accepted as payment in 1927? Gold coins? Yet the question, “How can he pay for all that?” can be asked about every character in every Woody Allen movie. Plausibility be damned, Woody just likes expensive-looking stuff.

With contemporary characters, all this conspicuous consumption can be irritating because they are outcompeting us. In contrast, Woody’s love of opulence is pleasing when set in the past. Fitzgerald’s Marcelled hairdo of shiny waves would be annoying if, say, Justin Timberlake were paying to have it done now. Yet when a style is 85 years out of fashion, it’s hard not to enjoy it.

Allen is aware that 1920s artists are dauntingly esoteric material for 21st-century audiences, so he keeps his jokes on the nose. It’s all very predictable for anybody who has seen a half-dozen Woody Allen movies. Still, watching a master craftsman rummage through his well-worn bag of tricks with the sole intention of making his audience happy for 90 minutes is deliriously infectious.