February 29, 2024

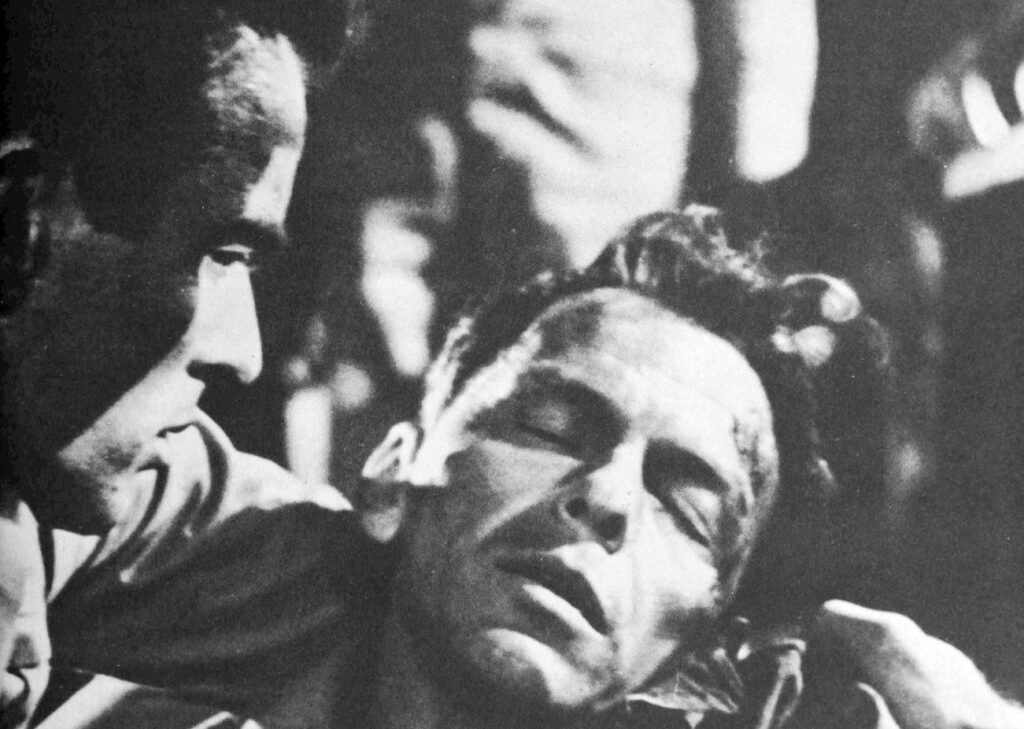

Montgomery Clift and Frank Sinatra, From Here to Eternity

Source: Public Domain

The late ’60s and early ’70s were great years for yours truly. Sporting successes in tennis and karate, a great president in the White House, and some good reporting from Hue for National Review’s William Buckley had given me a career boost. That’s when Bill, a very good friend, decided Paris would be a safer place for an eager young Taki to make his name. There was another reason Bill picked the City of Light as my base. A young Austrian princess, Alexandra Schoenburg, and I were tripping the light fantastic in Parisian nightclubs, and I had introduced her to the Buckleys. She had asked Bill for no more Vietnams.

The longtime Paris correspondent for The New Yorker, Janet Flanner, had successfully published an opus called “Paris Was Yesterday,” so Bill thought an article called “Paris Really Was Yesterday” a hopeful upgrade. Well, all I know is I’ve written of this three times at least over these past fifty years, but I can’t resist one more because it illustrates the kindness and total lack of self-worship—to which today’s celebrities are so addicted—of a wonderful writer named James Jones. For any of you young whippersnappers unfamiliar with Jones, he wrote the great bestsellers From Here to Eternity and Some Came Running, both very successful in print and as movies, and many other novels.

Jones and family lived in a grand house on the Left Bank in Paris, but rumor had it that he was going back to America. Jones was a close friend of Irwin Shaw, another terrific storyteller, author of bestsellers like The Young Lions, Two Weeks in Another Town, Evening in Byzantium, Lucy Crown, and Rich Man Poor Man, and some extremely good short stories like “Girls in their Summer Dresses,” “The Eighty Yard Run,” and “Tip on a Dead Jockey.” I had skied and played tennis with Irwin, who had encouraged me to write, but I was unable to contact him in order to get an introduction to Jones, who was perfectly placed to tell me why Paris was yesterday.

So, on an evening I’ll never forget, I drove by Rue de Berry, where the old Herald Tribune was based, left Alexandra in the car, dropped a jeton in the wall telephone, and rang James Jones. A gruff male voice answered.

Me: May I speak with Mr. Jones, please?

JJ: I’m Jones.

Me: Mr. Jones, my name is Taki Theodoracopulos and I work for William Buckley’s National Review and would like an interview with you.

JJ: I do not give interviews, sorry.

Me: Not as sorry as I am, sir, as I just got back from Vietnam and have a wife and three children to feed on eight thousand per year. An interview with you would help a lot.

JJ: Jesus, who did you say you work for?

Me: William Buckley’s National Review.

JJ: God help us, you better come around.

And so I did. Jones was wonderful. He had enough of Paris, was not in good health, and was eager to go home. The student revolt of 1968 had changed the carefree glamour days that had lured the chic and the intellectuals since time immemorial; now it was America’s time. He didn’t talk about himself or his work, but mostly about what Paris meant before and now, especially to American expatriates like himself. He was generous and kind, and tried to explain that the Paris of Papa Hemingway and Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald was no more, that he had tried to live the dream and now it was all over. Paris was just another city in trouble.

As I was leaving, his wife came in and we shook hands. She was extremely polite and asked if there was anything they could do for me. Slightly embarrassed, I thanked them profusely and left. I then wrote the story, telexed it to NR, and that was that.

A while later, Time magazine ran a cover story with the headline announcing the death of the novel. Irwin Shaw and the Joneses were dining in a Parisian bistro and discussing the Time article. “Who the hell do they think they are?” said Irwin. “We are storytellers, and we will always tell our stories, and to hell with Time and their bulls—.” “Don’t take it so bad,” said James, “I had a kid in my house the other day, and he makes eight thousand a year working for that fascist rag of Bill Buckley’s. I can’t pronounce his name, it was a long Greek one.” “Funny,” said Irwin, “the only Greek I know who writes is Taki Theodoracopulos.” “Yes, that’s the one,” said James.

Well, said Irwin Shaw, laughing in his drink, “You’ll be pleased to know, dear Jimmy, that next week I will be going on his sailing yacht in the South of France, and I’m rather looking forward to it.” “F—,” yelled James Jones, slamming the table, “I’ve been had by a Fascist.”

Years later, when I was a columnist for The Spectator, Esquire, and the London Sunday Times, I attended a Southampton, L.I., party in honor of Irwin Shaw, who was toward the end—James Jones had died—and Mrs. Jones approached me as I was talking to Irwin, who was laughing about the incident. “You never fooled me for a minute,” said Mrs. Jones. I’m not so sure.