December 03, 2009

The sharply contrasting careers of two Slavic-American artists who both died in 1987, the droll commercial illustrator Andy Warhol and the titanic sculptor Stanislaw Szukalski, illustrate much about how culture has changed over the last century.

For over 40 years, Warhol (1928-1987) has been famously famous for saying, “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” Warhol’s own renown, however, is undying. Last week, for example, saw the opening of a musical with the onomatopoeic title POP! about Warhol’s shooting by an irate feminist in 1968.

In contrast, Szukalski (1893-1987) spent much of his life on the edge of poverty. Yet, Szukalski actually was suddenly famous in his native Poland in the late 1930s. Then, much of his life’s work was blown to smithereens during WWII.

The great screenwriter Ben Hecht, who had met him in Chicago in 1914, wrote of him in the 1950s:

His works are vanished. He is without public, without critics, and so complete is the world’s ignorance of him that he may as well have never existed.

Yet, Szukalski toiled on, endlessly creating statues and drawings, a living legend to a handful of friends, including the very young Leonardo DiCaprio in 1980s Burbank.

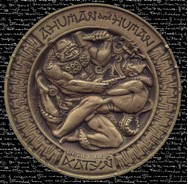

Szukalski’s politics weren”t helpful. In Chicago in 1914, to which his blacksmith father had brought him a half decade earlier, he was training 20 Polish boys in the manual of arms, “So when the time comes they will be ready to go back and fight for the freedom of Poland.” Polish nationalism, however, was not exactly the most career-promoting ideological obsession for a 20th-century artist. To the right is his plate, Ahuman and Human commemorating the Soviet massacre of the young leaders of Poland at Katyn in 1940, shows an ape in a Soviet Red Army uniform shooting a Pole in the back of the head.

Szukalski’s politics weren”t helpful. In Chicago in 1914, to which his blacksmith father had brought him a half decade earlier, he was training 20 Polish boys in the manual of arms, “So when the time comes they will be ready to go back and fight for the freedom of Poland.” Polish nationalism, however, was not exactly the most career-promoting ideological obsession for a 20th-century artist. To the right is his plate, Ahuman and Human commemorating the Soviet massacre of the young leaders of Poland at Katyn in 1940, shows an ape in a Soviet Red Army uniform shooting a Pole in the back of the head.  To the left is Yaltantal, presumably a reference to how the fate of Poland was determined at the Yalta conference without the Poles having a say.

To the left is Yaltantal, presumably a reference to how the fate of Poland was determined at the Yalta conference without the Poles having a say.

Moreover, his aesthetics were out of fashion in the middle of the 20th century, when abstraction ruled and his genius for representation was disdained.

And while the art world talked a good game about demanding “disturbing outsider” art, Szukalski works are mostly too grotesque to furnish a corporate lobby. Szukalski’s endless invention, tortured subjects, and Pre-Columbian tastes give the unsettling impression that this is what the leading artists of the Aztec Empire would be creating today if the Conquistadors had been defeated.

Finally, late in his life, the postmodern era rejected artistic heroism for Warholian irony. The sculptor liked to say, “I put Rodin in one pocket, Michelangelo in the other, and walk towards the sun.” His 75-year-long career pushed the 19th-century Romantic and early 20th-century Avant-Garde conceptions of the artist as a mad genius creating disturbing works to hilarious new extremes at a time when the art world was coming instead to idolize clever businessmen like Warhol.

As C. van Carter pointed out to me, Szukalski’s fan Jim Woodring wrote in “The Neglected Genius of Stanislav Szukalski“:

Among his most strongly held (and extensively documented) theories was the notion that a race of malevolent Yeti have been interbreeding with humans since time out of mind, and that the hybrid offspring are bringing about the end of civilization. As proof of this, he pointed to the Russians.

Szukalsi dared the world that his stupendous talent would make it forgive his megalomania, obstreperousness, obsession with vicious apes, general craziness, and exquisitely bad manners, the way it had forgiven Beethoven, Wagner, and so many other artistic heroes.

It didn”t.

Warhol, in contrast, invented a more consumer-friendly role for the artist in a culture tiring of greatness. Andy pointed out, “Art is what you can get away with.” He glibly churned out pictures of things people didn”t mind looking at, such as Marilyn Monroe and popular consumer packaged goods, while offering critics enough of a toehold to concoct rationalizations of why this was still Art.

Warhol, in contrast, invented a more consumer-friendly role for the artist in a culture tiring of greatness. Andy pointed out, “Art is what you can get away with.” He glibly churned out pictures of things people didn”t mind looking at, such as Marilyn Monroe and popular consumer packaged goods, while offering critics enough of a toehold to concoct rationalizations of why this was still Art.

Paul Johnson dyspeptically observed in Art: A New History

Paul Johnson dyspeptically observed in Art: A New History: “He was not so much an artist, for his chief talent was for publicity, as a comment on twentieth-century art, and as such a valuable person, in a way.” But lots of people liked the fact that he was making a joke out of Art-with-a-Capital-A.

Although he cultivated an image as a halfwit too dumb to get the joke (here’s a video clip from Basquiat in which Andy, played by David Bowie, loses an argument over whether the suburb of Saddle River is in New Jersey or New York), he got away with virtually everything he tried. If he who dies with the most toys wins, then the shopaholic Warhol, whose countless possessions required a 1988 Sotheby’s auction lasting ten days to dispose of his purchases to his fans, won.

Szukalski was a product of a more monumental age. Hecht recounted his 1914 introduction to Szukalski’s works:

I had never seen any statues like them, nor have I yet after thirty-nine years. They were like a new and violent people who had invaded the earth. They seemed to be

without skins, and their sinews writhed like imprisoned serpents. … Secrets animated all the statues, and I was bewildered looking at them those first fifteen minutes.

After Poland’s catastrophe, Szukalski wound up in Burbank making maps for an aerospace company. Some leaders of the underground comix scene, such as R. Crumb, Glenn Bray, and George DiCaprio, rediscovered Szukalski in his extreme old age.

After Poland’s catastrophe, Szukalski wound up in Burbank making maps for an aerospace company. Some leaders of the underground comix scene, such as R. Crumb, Glenn Bray, and George DiCaprio, rediscovered Szukalski in his extreme old age.

Struggle: The Art of Szukalski

Struggle: The Art of Szukalski:

A flood of political disaster, a capricious tide of artistic dogma almost overwhelmed his creations and submerged them in a sea of dark obscurity. … He was a Polish mystic and a Promethean artist whose message, in borrowed typeface from a dead language, would mean: “Help Yourself to the Sacred fire.” It is prankish that he is still so unknown.

Szukalski is perhaps the most memorable character in Hecht’s exuberant 1954 autobiography, A Child of the Century. In the company of his friend Wallace Smith, a journalist who illustrated his articles with his own drawings, Hecht first met Szukalski in 1914 in the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue:

“Excuse me for not standing,” Szukalski said. His voice was purring and nasal and Polish-accented. “I fainted in the street an hour ago. Now I feel better.”

“Are you sick?” I asked.

“No, … I am hungry. I have not eaten for several days.” …

“My friend Wallace [Smith] is an artist,” I said. Stanley looked at him. His eyes were still dizzied with hunger but he managed to get a sneer into them.

“Everybody who can draw better with the right hand than the left is an artist today,” Stanley said. His face grew paler. It looked up mockingly at me. “You are very lucky to know an artist,” he continued. “I do not know one”anywhere in the whole world.”

Almost 70 years later, the teenage Woodring visited Szukalski in his over-stuffed two-room apartment in Burbank. Szukalski hadn”t much changed:

During my first meeting with him, he had me continually off-balance. “What is your nationality?” he asked me moments after we settled down on chairs in the dank aquarium of his living room.

“Dutch, mostly,” I said.

“The Dutch are the world’s leading proponents and producers of child pornography,” he replied.

Hecht wrote:

Szukalski, in his own soul, was a country called Poland. I do not understand the process by which an egomaniac such as Szukalski can transform himself into the colors of a flag. But such he was”patriot, chauvinist and lover of Poland, blind with the homesickness of a fish for water. No other history, problems or people existed for him than those of Poland.

In his later years, he wrote a book entitled Behold!!! The Protong

In his later years, he wrote a book entitled Behold!!! The Protong, in which he argued that all human culture is descended from Easter Island, and Polish is the closest to the proto-tongue.

Back in 1914, the insulted Wallace Smith had been dumbstruck by the first Szukalski statue he had beheld: “His own face had lost its mockery. I became aware that Wallace was looking at his own talents turned into genius, his own fanatic draftsmanship made alive by art.”

When Smith asked the sculptor where he had learned his anatomy, Szukalski replied that once he had gone to meet his beloved blacksmith father, only to find:

“He had been killed by an automobile. I drive the crowd away and I pick up my father’s body. I carry it on my shoulder for a long time. We go to the county morgue. I tell them this is my father and I ask them this thing which they did allow. My father is given to me and I dissect his body. I study him carefully. You ask me where I learn anatomy?”

Szukalski looked at us with pride.“My father taught me,” he said.

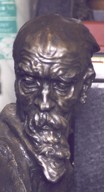

(Here’s Szukalski’s bronze, My Blacksmith Father, pre-dissection.)

(Here’s Szukalski’s bronze, My Blacksmith Father, pre-dissection.)

Two weeks later, Hecht and Smith brought Count Monteglas, the art critic for William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago Examiner, to the loft to discover the unknown Szukalski:

“Very interesting,” Monteglas finally said and raised his cane. He poked Aesop’s torso gingerly with the tip of his cane. “Very strong. Very well done. And there, too, great feeling.” Count Monteglas poked Aesop’s shoulder with his debonair stick.

“Excuse me,” said Szukalski, purring and nasal, “but people do not look at my statues with cane. They look with eyes.”

He stepped swiftly up to the critic, snatched the cane from his hand, broke it across his own knee and flung the parts out of the door. This done, he collared Count Monteglas and shoved him violently forward.

“Outside, please!” he said.

Here’s his Judas from 1912, when he was 19.

Woodring notes that in the 1980s:

One time I arranged to bring him to meet with the curator of a major Los Angeles museum. The man’s office was hung with works by Picasso, Matisse, and Kandinsky; Szukalski immediately launched into a sneering tirade against these masters. The curator simply left the room and a secretary showed us out.

Here’s his California Man.

Once, in his Burbank exile, about 70 people showed up to see a slide show of his work:

Szukalski was ecstatic. He loved to hold forth and he felt affectionate toward his every audience. He mounted the podium and within four minutes had alienated or offended everyone in the place. In his opening remarks he praised Reagan to the heavens and dumped all over Picasso (he pronounced it “Pick-ass-oh”); he denigrated art collectors, Russians, FDR, California, America and professional sports, and wound up with a stern denunciation of “homos.”

Note that Szukalski’s infinite love of Poland did not extend to traditional Polish artistic motifs. Over time, his work took on a bizarrely Pre-Columbian cast, as if he were the Michelangelo of the Mayans. Here, for example, is his model for the Rooster of Gaul. Woodring explains the artist’s conception:

Note that Szukalski’s infinite love of Poland did not extend to traditional Polish artistic motifs. Over time, his work took on a bizarrely Pre-Columbian cast, as if he were the Michelangelo of the Mayans. Here, for example, is his model for the Rooster of Gaul. Woodring explains the artist’s conception:

During his last years Szukalski’s major project was a gigantic and complex structure that he wished the U.S. to give to France to reciprocate for the Statue of Liberty. He called it the Rooster of Gaul. … “Look,” he said, indicating a weary and anguished woman being ravaged by a roiling mass of stylized and inscribed tentacles. “That is the woman who symbolizes France. She is being crushed and ensnared by all the “-isms” of modern Europe. There is Fascism, and there is Communism … and there is Ventriloquism.”

We, of course, live in the Age of Warhol, not Szukalski. We all are deathly afraid of not getting the joke.

We, of course, live in the Age of Warhol, not Szukalski. We all are deathly afraid of not getting the joke.

And yet, if Szukalski had only lived two years longer, to 1989, his mania for Polish liberty would have been vindicated. “The freedom of Poland” turned out to be the single most effective cure for what ailed the world in the second half of the 20th century.