February 13, 2013

Queen Elizabeth I

The long reign of the philoprogenitive King Edward III proved that when it comes to heirs, you can have too much of a good thing. He died in 1377, leaving not just “an heir and a spare” (as the current Prince of Wales has contrived to do), but five legitimate sons and three daughters.

For the next two centuries, Edward III’s descendants fought a “cousins’ war” for the throne, coalescing into two main rivals, the House of York (whose symbol was the white rose) and the House of Lancaster (the red rose). In the 19th century, Sir Walter Scott christened this struggle that climaxed on Bosworth Field the “War of the Roses.”

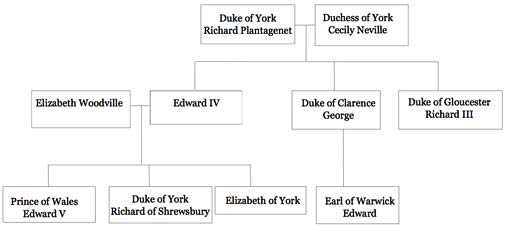

A couple of decades earlier, the House of York had taken the throne away from the Lancastrian Henry VI, making Edward IV king. Here, thanks to Wikipedia, is a simplified family tree:

While Edward IV was king, his brother, George, Duke of Clarence, was “privately executed” for treason in the Tower of London. Shakespeare presents this killing as part of Richard’s machinations to eliminate future rivals.

Edward IV died in 1483. His will made his younger brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, the Lord Protector of his 12-year-old son, the new King Edward V.

But before the lad could be crowned, the ambitious Richard induced Parliament to declare his late brother’s marriage illegitimate, rendering Richard’s wards bastards. This law also implied that Richard’s brothers had been cuckoo’s eggs themselves, making Richard the only true heir. Richard had himself crowned king.

The little ex-king and his younger brother disappeared in the Tower of London and were never seen again. To shore up his claim to the throne with a dynastic marriage, Richard set about wooing his brother’s daughter, Elizabeth of York.

Interestingly, over the course of the two centuries between the death of Edward III and the gradual decision of Elizabeth I to stop executing threats to the throne, 42 of the 47 royal victims were various kinds of cousins of their killers. Only five were closer relations: one brother, two uncles, and two nephews (the tragic “princes in the Tower” who Shakespeare claims were smothered at Richard III’s command).

In other words, Hamiltonian nepotism was more powerful than Triversian sibling rivalry during the Cousins’ War.

These statistics help explain Richard III’s exceptional notoriety. Kingship was a bloody business, but most of intra-royal executions were of cousins, often distant cousins. If Shakespeare is to be believed, Richard III was guilty of three of the five killings of closer-than-cousin relatives over two centuries of turmoil.

Of course, the Ricardians don’t believe Shakespeare. And I’m not equipped to play 15th-century detective over who murdered the princes in the Tower.

Then, Henry Tudor, who claimed to be a Lancastrian via his mother’s illegitimate ancestry, invaded from exile in France and overthrew the king. In the last speech in Richard III, the new king announces that, as leader of Lancaster, he will marry the slain Richard’s niece, Elizabeth of York:

We will unite the white rose and the red…

And let their heirs, God, if thy will be so,

Enrich the time to come with smooth-faced peace….

This dynastic marriage’s heirs would include Henry VIII, who divorced England from the Pope’s influence, and Elizabeth I, whose navy’s victory over the invading Spanish Armada in 1588 brought the English the peace and self-confidence necessary for the cultural climacteric of the Shakespearean Era.

Dynastic marriages have long been seen as a solution for otherwise insoluble political difficulties (although Paul Johnson argues that they mostly only multiplied plausible claimants to the throne). In the case of the War of the Roses, this dynastic marriage more or less worked. Scion Henry VIII’s Reformation set off a new round of Protestant v. Catholic squabbling that went on until 1688, but he did embody the satisfactory resolution of the York v. Lancaster fight.

I’ve long argued that the meteoric success of Barack Obama’s 2004 keynote address at the Democratic convention stems from his devoting the first 390 words to his ancestry, which culminates in the “improbable love” between his black father and white mother: a symbolic dynastic marriage between America’s main races.

Of course, Obama has mythologized his parents’ tawdry history: a 17-year-old girl with jungle fever knocked up by an already married man, a bigamous wedding, and then little evidence that they ever even made a home together. (Being Obama, a man who would rather mislead than flat-out lie, the politician left himself the lawyerly out: “Hey, I said it was ‘improbable.’”)

I suspect that Obama’s improbable rise to the presidency originated in his having introduced himself to the American people as the product of a figurative dynastic marriage that united the white rose and the black. By his dual nature he would…somehow or other…solve America’s race problem as permanently as the marriage announced at the end of Richard III solved England’s rose problem.

The details of how this would work were always a little fuzzy, but the message was clear: Elect Obama president.