October 14, 2012

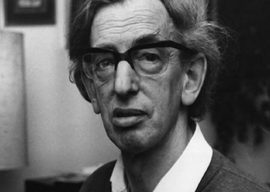

Eric Hobsbawm

Hobsbawm came to London at age 15 from Berlin in 1933, the year Hitler came to power. He soon joined the British Communist Party. At Cambridge University, he was a member of the notorious Apostles, a secret club whose membership in the 1930s was mainly communist. Several members at this time who later had jobs with access to British government secrets were eventually revealed to have been Soviet spies during the Cold War. These included Michael Straight, American speechwriter to Franklin D. Roosevelt and later publisher of The New Republic, who admitted spying for the Soviets to the American government in 1963.

Was Hobsbawm a communist spy as well? In 2007, he applied to see the files that MI5 kept on him. His request was rejected in 2009. To the press, he denied being a spy but mysteriously said that his request must have been turned down to protect the identities of those who had “snitched on me to the authorities.”

Either way, he did much more damage to the cause of liberty and democracy as a communist propagandist. In 1947, he was appointed a history lecturer at Birkbeck College in London, where he eventually became president.

Countless other members of the European intelligentsia who had fallen for communism abandoned the faith back in the 1930s as the murderous and miserable reality of what it entailed began to emerge.

But Hobsbawm was unable or unwilling to accept the brutal and clinical repression of all left-wing groups in the Spanish Civil War which tried to remain free of Stalinist control, as had George Orwell who saw it firsthand as a volunteer and wrote about it in his 1938 book, Homage to Catalonia.

After World War II, Hobsbawm minimized the horrors that communist regimes perpetrated everywhere. He distorted and corrupted the facts. In his 1997 book On History, he wrote:

Fragile as the communist systems turned out to be, only a limited, even minimal, use of force was necessary to maintain them from 1957 until 1989.

Perhaps he meant that such systems were wanted by and not imposed on the public in those countries, which is untrue.

He simply could not get enough of the Italian Communist Party, which nearly made Italy become Western Europe’s first domino to fall in the 1970s.

In his review of Hobsbawm’s 2002 memoir Interesting Times, British historian and Harvard professor Niall Ferguson cites this passage from Hobsbawm:

The Party…had the first, or more precisely the only real claim on our lives. Its demands had absolute priority. We accepted its discipline and hierarchy. We accepted the absolute obligation to follow ‘the lines’ it proposed to us, even when we disagreed with it….We did what it ordered us to do….Whatever it had ordered, we would have obeyed….If the Party ordered you to abandon your lover or spouse, you did so.

Yet this man was made a fellow of the British Academy in 1978, and in 1998 New Labour’s Tony Blair appointed Hobsbawm a Companion of Honour”one of the highest accolades for a British intellectual.

It is deeply disturbing that so many other influential people still not only take such a man seriously, they shower him with adulation. It makes me feel that there is one class war that really must be fought: The one to eliminate the chattering classes.