September 29, 2017

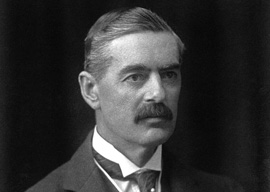

Neville Chamberlain

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Harris doesn’t gloss over Chamberlain’s faults: excessive self-assurance—even vanity—and an unwillingness to consult colleagues. Nevertheless his Chamberlain comes across as admirable, even heroic, in his determination to go as far as was possible to prevent war. Harris makes the point, too, that it was Chamberlain who drove forward the program to build fighters, while the chiefs of the Air Force—and Churchill in opposition—would have concentrated on building bombers.

One strange feature of 1938 is that Chamberlain and the leading members of his Cabinet were all too old to have served in the 1914–18 war, while the Tory MPs who opposed appeasement were, most of them, men like the future prime ministers Anthony Eden and Harold Macmillan who had fought on the Western Front. The men who hadn’t fought were more reluctant than the men who had to condemn the next generation to the horrors of war. In the not-very-long run, of course, appeasement must be held to have failed, because Hitler got his war anyway, if not at the time he wanted it. But Harris’ verdict is that Chamberlain’s decision to fly to Munich is defensible. It offered what proved to be the last chance to avoid another appalling war. Hitler, of course, spurned the chance because he was determined to have his war—a disastrous decision, as it turned out, for himself and his “Thousand Year Reich.” Breaking his word to Chamberlain led to his own downfall.

This will be my last regular column for Takimag. Thank you for reading me, even those readers who have taken issue, sometimes severely, with what I have written.