September 29, 2017

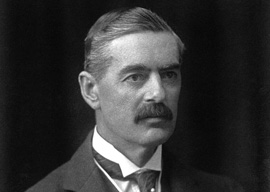

Neville Chamberlain

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The other evening I chaired an event in Edinburgh at which Robert Harris was introducing his splendid new novel, Munich. It’s sure to be a best-seller, deservedly, and Harris has reached a rare and enviable position in which his novels are translated even as he writes them; the German edition of Munich will be published in November, and Harris will be launching it in Munich, actually in the Führerbau, where Hitler, Chamberlain, Mussolini, and the French prime minister Daladier met. The last two took little part in the conference; it was a duel between Hitler and Chamberlain, and one that Chamberlain won. Not only that, but when war was for the moment averted, Chamberlain was cheered in the streets of Munich. It’s difficult for many to recognize even now that in 1938 the prospect of war seemed as frightening and terrible to the mass of the German people as it did to the British, French, and Italians.

This was still the case a year later. When war did break out in September 1939, the Berlin-based American journalist William L. Shirer remarked that there was no enthusiasm, but only apprehension, in the streets. It wasn’t like 1914 when there had been wildly enthusiastic crowds in Berlin, as indeed in Paris. In 1938–39 the horrors of the First War were too close, too vivid in memory. As for Hitler, he later said that September 1938 would have been the best time for Germany to go to war. To that extent Munich was a defeat for him; he felt cheated of the war he had wanted at the time of his choosing.

If Neville Chamberlain hadn’t gone to Munich, Hitler would have got his war then. The German General Staff thought it would take a month to defeat the Czechs and occupy Czechoslovakia; Hitler said it would take a week. He might well have been right. Meanwhile, in 1938 there was little appetite for war in either France or Britain; the British Chiefs of Staff reckoned they wouldn’t be ready for war until 1940. In 1938 the RAF had only one squadron of Spitfires—twenty planes. Over the next year 50 percent of U.K. government spending went to rearmament. 1940 was the earliest Britain could win the war in the air and prevent a German invasion.

Appeasement became very unpopular once war became inevitable. This was understandable; it was a failed policy that hadn’t prevented war and even seemed shameful. Nevertheless Chamberlain’s decision to go to Munich and negotiate with Hitler had one other important beneficial consequence: Hitler had agreed in Munich that the incorporation into the Reich of the Sudetenland, with its majority German population, was his last territorial demand in Europe. Six months later this was revealed as a lie. So, whereas in 1938 there was public reluctance in Britain to go to war to compel the Sudeten Germans to remain Czechs, in 1939 the mood was very different. War was accepted as unavoidable and the British people were united as they hadn’t been a year earlier.

Harris plays with the idea of anti-Nazi resistance to Hitler and the possibility of an army coup. There has always been talk of this, but he’s not convinced. Rightly, I think. It took five more years and the imminence of German defeat for the aristocratic opposition to spring the July plot. Before then, talk of a coup was met with the statement that Prussian generals don’t mutiny. Interviewed by the enigmatic Otto John in a British internment camp after the war, Field Marshal von Brauchitsch, Chief of the High Command in 1938, said it was all nonsense. He knew nothing about it (and he was the only man who could have given an order). The idea, he said, was madness; Hitler was “immensely popular.”