December 08, 2011

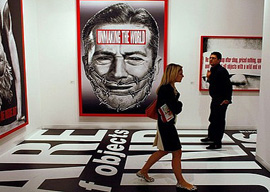

Art Basel Miami 2011

After the mid-1980s in America, liberalization led to financial innovations, and bankers came up with convoluted new stratagems to turn credit into derivatives, subprimes, and SIVs. These innovations delved below the surface, offshore, and into the shadows.

Florence in the fifteenth century was split between its vocation as a beacon of light and purity (a City of God, a New Jerusalem) and its position as a center for international finance and the consumption of luxury goods (silk from China, Egyptian cotton, leather, perfume, and jewels).

Bankers in fifteenth-century Florence were so wealthy that even rulers envied them. When Galeazzo Sforza, the son of the Duke of Milan, visited the Palazzo Medici in April of 1459, he was amazed at all he saw. “All this cannot come from mere money,” he exclaimed, gaping at the Fra Angelico paintings and the Donatello sculptures.

Money could buy it all in Florence in those days—a prayer as well as a prostitute, the first costing less than the second, which offended the devout.

Cosimo the Elder, founder of the Medici dynasty, once asked Pope Eugene IV what he could do to guarantee that God would “grant him mercy and the preservation of his earthly goods.” It would seem they were conflicting demands, but Eugene said both could be achieved by giving 10,000 florins to restore the convent of San Marco.

What else has changed? In fifteenth-century Tuscany, they had the Mount of Piety, a lending institution set up by the Church to replace usury with charity and Jewish moneylenders with Christian pawn shops.

Nowadays we have the IMF, set up by victorious nations after World War II to replace colonization with debt bondage.

Things are changing, though. The IMF used to lend to Latin America; now it is trying to borrow from them. Christine Lagarde was on tour last week, doing a “historic about-turn” and soliciting South American funds to help solve Europe’s debt crisis.

In a dramatic reversal, Cosimo, at the height of his power, was sentenced to prison and exiled in 1433. His crime, according to Machiavelli, was farsi grande—acting bigger than his boots.

“The Bible dictates that man should earn a living by the sweat of his brow, work was God’s plan for man, and usury is not work. On the other hand, it is access to credit that makes it possible to rise from one’s rank and subvert the status quo,” explains one of the essays in the exhibition catalogue.

Another talks of sumptuary rules that dictated how much gold a woman could wear and how many yards of fabric she could drape from her dress. (The ladies quickly found ways to get around the rules.)

These days you’d have to pay a girl to wear more than two, three yards. What else has changed? Men used to wear tights, and only noblemen were allowed to wear red ones. Now tights are for women, and hosiery is no longer underwear but often the main article of clothing—a fashion development that has handsomely profited my friend Francesco, who makes tights in the Tuscan hills. With the profits from the tights, Francesco bought himself a farm where he produces olive oil for his pleasure and his friends. I received two cans of it last month: liquid, transparent, golden, it is just as we want our banks to be!

The threads for making the tights come from all over the world: Italian wool, cotton from Turkey, cashmere and silk from the Orient, nylon and Lycra from, say, DuPont in Texas—made of crude oil, but that’s another story. They spin and dye the thread in San Miniato, sew two tubes together to make a pair of tights, and ship them to Barneys and Bergdorf Goodman. Art-world beauties buy them; sheathed in them, they will then sell art at the Miami Beach Convention Center. It is all tied together by a thread!

And therefore hanging by a thread? The Basel Accords aim to reduce risk by improving bank’s Liquidity Coverage Ratios and giving investors a better picture of the risks each institution runs; but opponents warn their implementation “will decrease annual GDP growth by 0.05 to 0.15 percentage points.”

About to be burned, Savonarola warned from the pyre: “O merchants, abandon your usury, return the ill acquired and the goods of others, otherwise you will lose everything.”

In the fifteenth century, friars predicted the future; now it’s done by numbers. Men wore the tights; now women do. Bankers used to commission art; now they invest in it.

What else has changed? In those days, bankruptcy was just a broken bench.