December 08, 2011

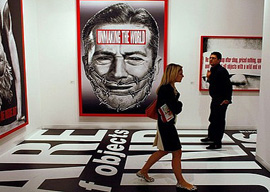

Art Basel Miami 2011

In Miami Beach on Monday morning, the convention center was strewn with cardboard, Scotch Tape, Styrofoam peanuts, and other packing litter. The hotel bars were littered with hung-over Europeans loitering over their Scotch and peanuts, the aftermath of Art Basel Miami Beach.

For ten years now Basel has exported a very successful contemporary art fair, the summit for art dealers worldwide. And for a little over two decades it has exported banking rules, voluntary directives agreed upon by a summit of central bankers from around the world.

Basel I was adopted in 1988, principally to establish credit-risk ratings, ranging from zero for home-country sovereign debt to one hundred for corporate debt. In 2004 came Basel II, trying to set guidelines on how much capital a bank should maintain; and in 2008 came Basel III in response to the crisis.

It is not surprising that both Art Basel and the Basel Accords came to us from the same alpine city. Art and finance have always been linked, and before drifting across the Alps to Switzerland, both came from Italy.

I recently received several things from Italy: two cans of homemade olive oil from San Miniato, an exhibition catalogue from Florence (Money and Beauty. Bankers, Botticelli and the Bonfire of the Vanities—at the Palazzo Strozzi, a fascinating show if anyone is in the area), and from Siena the news that Monte dei Paschi, the world’s oldest bank, was at risk of going under.

From Florence to Florida and from the fifteenth century to the twenty-first, what has changed?

There are many bankers at Art Basel Miami Beach. In the fifteenth century bankers went to fairs, too—not to sip champagne but in the province of Champagne. Behind their bench with their abacus and scales they counted florins. When one of them went bust, his bench was cut in two to symbolize his demise—banca rotta, broken bench, bankruptcy.

Florence was a major banking center in those days and was very rich; it also suffered from spiritual unrest. Under friar Savonarola’s leadership, gli Arrabiati, the Angry Ones (also known as i Piagnoni, the Whiners)—were calling for more stringent moral standards. Displaying a keen sense of showmanship, they collected fancy clothes, paintings, books, and other symbols of luxurious decadence and burned them on the town square.

Higher moral standards are also what they are asking for in Zuccotti Park, yes? Except they seem to have abandoned the introspective and confessional aspects. On top of finger-pointing, Savonarola and his followers also practiced self-flagellation.

After the whole bonfire-of-the-vanities thing, Florence banned usury. Bankers came up with convoluted new stratagems to turn what on the surface was a letter of credit—a simple money transfer from one place to another—into an interest-bearing loan.