February 16, 2022

Source: Bigstock

Besides being a black woman at a time when the Biden administration is publicly committed to appointing a disproportionate number of black women, economist Lisa D. Cook’s prime qualification for her nomination to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve is a celebrated paper on black inventors. Her work raises one of the more troubling issues in political philosophy.

While most economists are agreed that the capitalist system generates more wealth than any other, what if capitalism can never generate what is now called “equity”: equal outcomes by race and sex?

What if—no matter how thoroughly any and all discrimination, abuse, and unfairness is rooted out of the capitalist system—blacks and women will on average be less likely to strike it rich than whites and men?

What if, after all inequalities of input are finally erased, the African-American who invents the Next Big Thing is more likely to be another Pretoria-raised Elon Musk? What if the next Steve Jobs is still likely to be a man and the next Elizabeth Holmes a woman?

Economists are not a notably sentimental lot, so some are no doubt brave enough to shrug and say, “Well, maybe that’s the way the world works.”

But on university campuses in the current year, these are not questions with which all professors of economics are happy to publicly wrestle. A safer approach is to blame any shortcomings in the performance of the good people like Lisa Cook on the bad people: i.e., white men.

Hence, the acclaim for Professor Cook’s 2014 paper “Violence and Economic Activity: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870 to 1940.” Cook explains:

I extrapolated the trajectory from the pre-1900 trend and found that in the absence of violence and segregation, there should’ve been roughly 1100 patents at the time. That would’ve been the output of a mid-sized European country then. But what I found was 726 patents.

Cook spent several years carefully coming up with a list of 726 patents granted to black inventors over the 71 years of a golden age of American invention from 1870 to 1940, or 10.2 patents per year. Considering that most African-Americans were legally enslaved up until 1865, each one was an impressive accomplishment. Yet, in the extraordinarily inventive Thomas Edison Era when Americans were averaging over 25,000 patents per year, ten is not a big number.

In contrast, a 2020 paper by Michael J. Andrews and Jonathan T. Rothwell came up with an estimate of blacks garnering 49,821 patents over the same years, 69 times more than Cook’s count of 726. Either Cook or Andrews & Rothwell must be wrong. Likely both are off by a considerable amount, with the real number in between.

Cook’s figure of 726 is almost certainly an understatement, a testament to her scholarly caution.

Cook’s source for 65 percent of her listings was Henry E. Baker (1857–1928), an African-American examiner in the United States Patent Office. Baker helped conduct sizable federal mail surveys in 1900 and 1913 of patent attorneys and other experts asking for the names of black inventors to honor. Baker then checked the responses against the files.

He ultimately published the claim that he’d verified 821 patents issued to blacks, with 505 leads left to follow up. Baker also asserted that his list probably comprised only half of all black patents. And given another 27 years from 1913 to 1940, all in all, it seems not implausible that blacks might have earned several thousand patents during these 71 years rather than just Cook’s list of 726 trustworthy ones.

On the other hand, whatever the exact real number, the black contribution over that fecund time period was less than staggering. Americans in total earned 1,893,200 utility patents, or 26,665 per year.

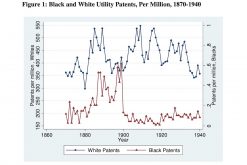

Cook decided she had discovered something previously unasserted in the historical record: as shown in her graph, a sudden and permanent massive decline in patents issued to blacks (red line) from 1899 to 1900:

Cook blames this apparent decline in 1900 on the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” decision back in 1896, as well as lynchings (which peaked in 1892) and antiblack rioting by whites. (The quite different methodology used by Andrews & Rothwell, however, sees black patenting as largely stable over time.)

In a blog post extolling Cook’s fitness for the Federal Reserve post, Nobel laureate economist Paul Romer says he learned much from Cook’s graph:

The surprise for me was the size of the effect on black patenting at a time when the control group of white inventors shows no comparable change. Had I considered the effect that changes in personal security can have on an activity like patenting, I might have concluded that it could have some effect, but I would not have expected the effect to be so large. After Lisa’s evidence forced me to think again about how easy it is to take personal security for granted and about the profound effect that a lack of personal security can have on optimism and a willingness to invest in the future, it seems entirely plausible that the threat of violence that prevailed during the Cultural Revolution in China, during reform in Russia, or in South Africa today can depress the activities required for economic growth.

Well, yeah, most of us figured that out even before they gave us the Nobel…

But what if the Fed nominee didn’t actually discover what she, Romer, and Biden’s economic advisers think she discovered? What if, instead of having made an epochal discovery, Cook is mostly just confused?

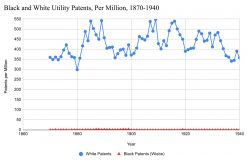

First, let’s look at Cook’s much-admired graph more closely. She misleadingly uses a double-axis graph with, on the left, whites’ patents per million running from 150 to 550, while, on the right, blacks’ patents per million go from 0.0 to 1.0.

It would be legitimate to use a dual-axis graph when you are looking at two variables on completely different scales, such as average temperature and inches of rainfall. But if you are instead comparing the same measure but with wildly different quantities, the standard procedure is to use a log scale.

When you do what Cook did, readers will often just plain get it wrong. For example, Cook’s NPR interviewer looked at her graph and then told the public:

African Americans filed patents at roughly the same rate as white inventors through about 1900.

No, they didn’t. If you stare at the graph long enough, you’ll figure out that Cook’s graph is actually saying that in their best year in her database, 1899, blacks earned patents about 1/550th as often as whites per capita.

But that’s also wrong because Cook botched up the scale of her right axis. She made an arithmetic error that leads her to understate how many patents per capita blacks earned. Taken literally, her graph says that in some years, the approximately 10 million U.S. blacks earned between zero and one patents, which is impossible.

Nike data scientist Michael Wiebe theorizes that instead of dividing patents earned by blacks by the number of millions of blacks, Cook ineptly divided by the number of millions of whites. (In other words, her most famous graph is a fiasco, although the shape of the lines is more or less unaffected.) Wiebe’s work suggests as a quick fix multiplying her figures for patents per million blacks by 6.66. So, in halcyon 1899, Cook’s corrected data shows blacks earning 1/83rd as many patents per capita as whites.

Making Wiebe’s adjustment, here’s what Cook’s graph would look like (eyeballing her data off her graph) just plotting both whites’ and blacks’ rate of patenting against a single conventional left axis:

In truth, despite the vast attention paid to old black inventors these days—hilariously, candidate Joe Biden announced in Kenosha, “Why in God’s name don’t we teach history in history classes? A black man invented the light bulb, not a white guy named Edison”—black inventors, although highly admirable as individuals, didn’t contribute all that much to the American economy as a group.

Or to put it another way, African-Americans in the North were respectably inventive by the standards of most times and places in human history, just not by those of Mark Twain-era Connecticut Yankees.

So, why did the number of black patents in Cook’s database nosedive from 1899 to 1900?

It’s true that the Democrats were working to worsen conditions for blacks as Jim Crow was imposed in the later 19th century.

But blacks were simultaneously helping themselves by building their human capital as they slowly came Up From Slavery, to cite the title of Booker T. Washington’s best-selling 1901 autobiography. For instance, the black literacy rate rose steadily from only 20 percent in the 1870 Census to 89 percent in the 1940 Census.

Republican politicians tended to be vaguely sympathetic toward black progress. The GOP Congress voted $15,000 to put on a laudatory “Exhibit of American Negroes” in the U.S. pavilion at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. Numerous top men of the race contributed to this successful undertaking, such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Henry E. Baker, an examiner in the U.S. Patent Office.

For years, Baker had been keeping an informal list of black inventors, but patent documents didn’t ask for the race of the applicant.

To find the names of black inventors to honor in Paris, the Commissioner of Patents sent out on Jan. 26, 1900, a mass mailing to patent attorneys and other experts asking for any information they might have on blacks who had achieved patents.

Baker checked the responses against the records and oversaw the creation of a four-volume collection of 370 patents won by African-Americans that was displayed in Paris. Two years later, Baker republished his list in a chapter in the anthology Twentieth Century Negro Literature.

Baker’s 1900 list of 370 patents makes up over half of Cook’s 2014 list of 726.

That’s why in Cook’s archive, patents plummet from 1899 to 1900: Her single best source dates to late January 1900. In truth, there wasn’t a sudden decline from 1899 to 1900, there was just better coverage of 1899 than of 1900 due to the excitement over the 1900 Exposition Universelle.

Approximately 102 more of her other data points originate in Baker’s later works following a Patent Office 1913 survey in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. (That appears to have been the last intensive search for black inventors until after WWII.)

Baker then announced he had extended his list to 821 patents “verified by office records,” an increase of 451 over his 370 in 1900. In articles in 1913 and 1917, he highlighted dozens of patents found in the new study. But he never got around to publishing the book in which he’d promised to detail the bulk of his new patents.

Refusing to take Baker’s word for his post-1900 results, Cook limits her archive to about 472 patents cited by Baker in identifiable detail. Lacking documentation, she doesn’t count the other 349 that Baker claimed to have found.

Cook then proclaims herself to have made a breakthrough discovery in economic history, when in truth she’s just forgetting it’s her own judgment call that led to the sharp fall in her database from 1899 to 1900.

Personally, I would trust Baker, who was known as a careful and honest man:

His most notable characteristic is his public spirit, having been connected with almost every well-directed movement in this city for the last fifteen years looking to the betterment of the condition of his race…. The estimation in which he is held by those who know him best is attested by the fact that he is invariably called to the position of treasurer in every organization of which he is a member.

So, if we take Baker at his word, then, contra Cook, black inventors were about as productive in the early 20th century as they were in the late 19th century. And that’s about what you’d expect: Democrats were trying to make life worse for blacks, but blacks were working to make themselves better.

But that things mostly kept on keeping on isn’t a very interesting finding to publish.

Does that mean Cook deliberately misled her readers? Probably not. She doesn’t seem that clever. As Upton Sinclair famously said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

Despite the Theory of Intersectionality that the Biden administration subscribes to so whole-heartedly in making their nominations, much the same is true for a black woman.