June 10, 2016

Source: Bigstock

Most of us can agree that Karl Marx got it wrong. It wasn”t only that the Revolution didn”t come in the advanced industrial and capitalist countries as he expected but in backward Tsarist Russia, which, despite rapid economic growth in the years before 1914, remained essentially an agrarian peasant society. More important, capitalism showed a remarkable ability to adapt. Employers didn”t, as he supposed, merely exploit their labor force, keeping wages low to maximize profits. On the contrary. Workers, it came to be realized, were, or could be, also consumers. Henry Ford understood that mass production of motorcars could be profitable only if there was a mass market in which to sell them. The car worker who earned enough to buy the cars that he helped to assemble might still resent the boss and the management, and depend on his union to negotiate good wages for him, but he wasn”t simply the exploited proletarian of Marx’s theorizing.

Capitalism survived its crises, the most serious being the Great Depression of the 1930s. Business cooperated with the developing state, with its zeal for regulation and its expanding social functions, to create the unprecedented and widespread prosperity of the Western world in the second half of the 20th century. There were dips””recessions,” in the language of economists”but the general trend was onward and upward. Capitalism continued to bestow its blessings, and in the past quarter of a century the world has grown richer than ever before, and countries long mired in poverty have experienced remarkable economic growth. The Western capitalist economy has gone global.

Almost sixty years ago a British prime minister, Harold Macmillan, remarked that “most of our people have never had it so good.” He was dead right. Moreover they, like the U.S. and the other nations of the developed world, have had it better since. At the time some thought Macmillan’s emphasis on the new prosperity rather vulgar. Few paid attention to his second thought, which had the old Whig pessimist wondering if it wasn”t perhaps too good to last. For a long time events seemed to make nonsense of his doubts. Our societies continued to get richer. Capitalism, in harness with the social state, flourished. It had its dicey moments, its ups and downs, but catastrophe was always averted. It still hasn”t arrived.

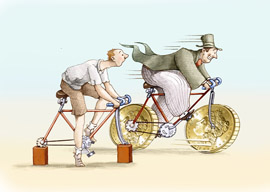

And yet, and yet, Marx may be moldering in his grave, but his ideas, in some form or another, aren”t quite dead. In the Western world there is an unusual degree of dissatisfaction with the workings of global capitalism. This is evident in the European Union, especially in France and the United Kingdom, and it is evident in this extraordinary presidential campaign in the U.S.A., the heartland of capitalism. The socialist Bernie Sanders has come closer to capturing the nomination as the Democratic candidate than any man of the socialist left in the history of the U.S.A. More remarkable still has been the success of Donald Trump, a success that is also bizarre. Trump is a very rich man who has done very well indeed out of global finance capitalism. Put a top hat on his head rather than the baseball cap he usually wears, and he could serve as the model for any of those old cartoons of the Wicked Capitalist. Yet his appeal is essentially to those Americans who feel, often with reason, let down by today’s global capitalism, indeed betrayed by it, who have found the American Dream turn bad.

What we are seeing is a protest against the inequalities of the modern world, against the huge and ever-deepening gulf between the superrich and the ordinary, hardworking, law-abiding citizens. That Trump himself is one of the superrich is an agreeable irony.

Many readers will remember the exchange between Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. The rich, said the romantic Scott, are different from us. “Yeah,” said the realist Hemingway, “they got more money.” Those who quote it usually assume that Hemingway had the better of the argument. Today, for many, both were right. The rich are different from us because they have got more money, much more money; and Hillary Clinton, once distrusted as a leftie, is now pilloried as a creature of Goldman Sachs and Wall Street. Chief executives enjoy what seem to the average salaried employee or wage earner to be grotesquely high salaries, with generous pension rights and golden handshakes when they move from one post to another, equally lavishly rewarded.

The resentment this inequality provokes is not surprising. It’s been festering for years, from well before the global financial crash of 2008. The surprise is that it has taken so long to come to the surface.

Back in 1997, the American philosopher, the late Richard Rorty, forecast that “the old industrialised democracies are heading into a Weimar-like period,” a time of confidence-sapping uncertainty.

“Members of labor unions and unorganized skill workers,” he wrote, “will sooner or later realise that their government is not even trying to prevent wages from sinking or to prevent jobs from being exported.”

Well, that day has arrived.

He continued: “Around the same time, they will realise that suburban white-collar workers”themselves desperately afraid of being downsized”are not going to let themselves be taxed to provide social benefits for anybody else.”

Well, we are living in that time now, too.

What would be the consequence? In Rorty’s opinion, “at this point something will crack. The non-suburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking for a strong man to vote for”someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and post-modernist professors will no longer be calling the shots.”