November 03, 2021

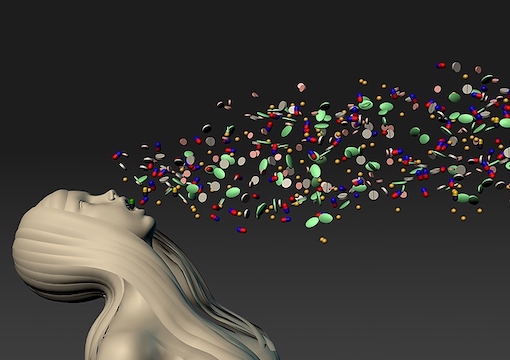

Source: Bigstock

With the CDC estimating last month that drug overdose deaths rose over 30 percent in the first twelve months of the pandemic to nearly 100,000, Sam Quinones’ outstanding new sequel to his award-winning 2015 book Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic is definitely timely.

Quinones’ The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth brings us up to date on the disastrous drug developments of the past half-dozen years.

Dreamland explained how the Sackler family promoting OxyContin to doctors as a “non-addictive” synthetic opioid painkiller in the late 1990s set off what I call the White Death that quietly killed so many working-class whites in the first decade of this century.

Then, as the medical profession became less irresponsible about writing pain-pill prescriptions, Mexican drug smugglers stepped in to supply cut-off pill addicts with heroin.

While Dreamland was superbly reported, its prose style was occasionally slightly off. In contrast, The Least of Us is elegantly written. And Quinones has perfected his method of merging big-picture cause-and-effect analyses of the economics and neuroscience of drugs with illustrative human-interest stories of Americans swept up in this national catastrophe.

First, the good news about what has happened since Dreamland: Heroin has largely disappeared from much of America.

The bad news: That’s because heroin has been replaced by the synthetic anesthetic fentanyl, which is much stronger and deadlier.

The worse news: Fentanyl is so cheap that drug dealers have taken to sprinkling it into most of the other drugs they sell, such as cocaine and methamphetamine, because a dash of fentanyl makes all drugs more euphoric. Plus, it’s extraordinarily addictive, so you can become a fentanyl addict without even knowing you have been ingesting it. You just want your dealer to sell you more of that good stuff.

On the other hand, you probably won’t be a fentanyl addict for long because just a tiny excess amount can kill you. And drug dealers aren’t good at quality control when mixing white powders. When stepping on their product, Quinones says, local dealers invariably rely on $29.88 Magic Bullet blenders, which are great at mixing liquids for smoothies, but are terrible at mixing powders, so nobody can tell how much fentanyl wound up in your particular dose.

Therefore, Quinones warns that the era of recreational drug use is over:

That concept belongs to a past when drugs were far more expensive, harder to procure and less potent and more forgiving…. Now, every line of cocaine, every “pill” [counterfeit OxyContins are often fentanyl] at a party is an invitation to Russian roulette. On the streets of America, there’s no such thing as a long-term fentanyl user.

Fortunately, in 2019 the Chinese government banned fentanyl manufacturing. Unfortunately, Chinese companies responded by exporting the raw ingredients to Mexican labs to manufacture and then sneak into America.

Quinones points out that the 21st-century history of drugs is supply-side-driven. Few drug addicts dream up new highs and make them happen. Instead, global capitalists, whether the Sacklers, Chinese manufacturers, or Mexican cartels and entrepreneurs, invent new drugs to solve their business problems.

Second, there’s more good news in The Least of Us: Crack, which was such a disaster for America in the late 1980s, is fading in popularity.

The bad news: Mexican crystal meth has taken over from crack. Meth, long the low-rent white drug, has spread to Latinos and now blacks.

The worse news: Meth is now really cheap because huge Mexican drug labs have replaced the old ephedrine-based meth with a high-volume recipe that Quinones calls P2P meth that can be made from common industrial chemicals without requiring any controlled substances like ephedrine.

The worst news: While the old ephedrine meth was a party drug, the poor man’s powder cocaine, the new meth can much more rapidly inflict monstrous brain-damaging psychotic side effects resembling schizophrenia, such as paranoia, hearing voices, and the destruction of memory and personality. These adverse events can set in within weeks of starting on modern Mexican meth and often don’t begin to fade until after six months or a year of abstinence.

Unfortunately, nobody has yet scientifically studied this question of why the new meth is even worse than the old. The author pleads:

I don’t know of any study comparing the behavior of users—or rats for that matter—on meth made with ephedrine versus meth made with P2P. This now seems a crucial national question.

Meth is an upper and fentanyl is a downer, so, at least, never the twain shall meet, right? Nowadays, though, addicts tend to cycle through both drugs to self-medicate. Meth covers up the withdrawal symptoms of getting off fentanyl, and then fentanyl seems to make meth heads act less crazy. Rinse and repeat until dead.

Quinones, who in the early 2000s reported on Latino crime for the Los Angeles Times while Jill Leovy covered black crime, accuses his old newspaper of covering up the most obvious reason for the huge increase in the numbers of homeless on the streets of Los Angeles over the past ten years: the inundation of Mexican meth.

Remarkably, meth rarely comes up in city discussions on homelessness, or in newspaper articles about it. Mitchell called it “the elephant in the room”—nobody wants to talk about it, he said. “There’s a desire not to stigmatize the homeless as drug users.” Policy makers and advocates instead prefer to focus on L.A.’s cost of housing, which is very high but hardly relevant to people rendered psychotic and unemployable by methamphetamine….

When asked how many of the people he met in these encampments had lost housing due to high rents or health insurance, Eric could not remember one. Meth was the reason they were there and couldn’t leave.

Quinones sees the tent cities of meth users that block sidewalks under the freeway even in my suburban neighborhood as “enabling communities” that shield addicts from what they need most: being called out for their bad behavior.

Reading The Least of Us suggests answers to a variety of random questions I’ve had about life in modern America. For example, why do many of the homeless have so much more stuff these days than in the old days when a shopping cart could carry all their possessions? One reason is because meth induces hoarding. “Nothing indicated meth-induced homelessness like a bicycle fixation.”

Also, although Quinones doesn’t cover meth’s bad impact on Native Americans, I wonder whether the rapid decline in mental acuity caused by the new meth might have something to do with the sharp fall in average SAT scores among students identifying as American Indian over the past half decade.

Another difficult question is how much are the new drugs contributing to the political craziness of our times. Quinones notes:

As I talked with people across the country, it occurred to me that the P2P meth that created delusional, paranoid, erratic people living on the streets must have some effect on police shootings.

One police department that studied this was Albuquerque, site of Breaking Bad, which had a high rate of police shootings over the past decade, although this didn’t attract much national media attention because few blacks live there. Police shootings doubled there after the new meth arrived, with 60 percent of the dead having meth in their system.

“We knew when the Mexican meth hit because people went crazier. Before that, police shootings were not common,” Cox told me. “Now there’s this new category of people starting shootouts with APD SWAT when they have one bullet and acting like they thought it would work.”

Similarly, early in 2021, there was much talk about a wave of seemingly random street violence against little old Asians, purportedly due to Trump having said the words “China virus” nine months before. But videos showed most of the malefactors were black.

One possibility that Quinones doesn’t mention could be that the recent drug surge into black neighborhoods that began in the mid-2010s might be increasing psychotic violence among black street people. Blacks have always had a higher schizophrenia rate than other races, and the new meth might be worsening their behavior.

In 2015’s Dreamland, he explained that Mexican heroin dealers avoided selling in shooting-inclined, attention-attracting big-city black neighborhoods in favor of white small towns that nobody cared about. But that kind of enlightened self-restraint can’t last forever in a competitive market.

How much is the rise in black-on-black shootings since Ferguson in 2014 related to the new drugs? (In general, the white Ohio River Valley towns hit worst by 21st-century drugs have not seen much gunplay.) The crack wars of three decades ago were extremely murderous because controlling crack-dealing turf was highly profitable, plus the drug itself brought out the worst in people. It’s hard to say yet whether either effect is currently happening with fentanyl or meth.

And what about the bizarre-looking Antifa crazies of Portland? Quinones did most of his reporting in places like Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia, but he mentions Portland in passing as having been hit hard.

What should be done about all this? Should we legalize drugs as the libertarian economists advise?

Quinones points to the End of History—capitalism’s triumph over communism in 1989—as the point at which capitalism lost “the one thing it claimed was essential to human growth: competition.” He adds:

I’m sympathetic to the idea of drug legalization…. The problem is, I don’t trust American capitalism to do drug legalization responsibly…. The opioid epidemic began with legal drugs, irresponsibly marketed and prescribed…. Our brains are no match for the consumer and marketing culture to emerge in the last few decades.

Nor has California’s move to decriminalize drug possession worked because it has removed much of the power of authorities to force addicts out of their sidewalk tents and into rehab.

Indeed, with drug-possession arrests dropping sharply in 2020 due to cops social-distancing and the racial reckoning, Quinones expects:

[We’ll] come to see the last ten months of 2020 and into 2021 at least in part as one long, unplanned experiment in what happens when the most devastating streets drugs we’ve known are, in effect, decriminalized, and those addicted to them are allowed to remain on the street to use them.

I.e., they die in larger numbers than ever before.

While Quinones doesn’t like seeing addicts sent to prison (and he thinks high-rise downtown jails are even worse for them than prisons due to the lack of exercise), Quinones is against decriminalizing drugs because he’s a big fan of judges threatening to send addicts to prison if they don’t get serious about getting treatment right now:

Waiting around for them to decide to opt for treatment is the opposite of compassion when the drugs on the street are as cheap, prevalent, and deadly as they are today. We used to believe that people needed to hit rock bottom before seeking treatment…. Today, rock bottom is death.

He sums up:

In a time indeed when drug traffickers act like corporations and corporations like drug traffickers, our best defense, perhaps our only defense, lies in bolstering community. America is strongest when we understand that we cannot succeed alone, and weakest when it’s every man for himself….

I find comfort that much of what neuroscience has learned about our brains confirms religion’s truths: humans need love, purpose, compassion, patience, forgiveness, and engagement with others. We’re built for simple things—for empathy and community. That is our defense.