January 15, 2021

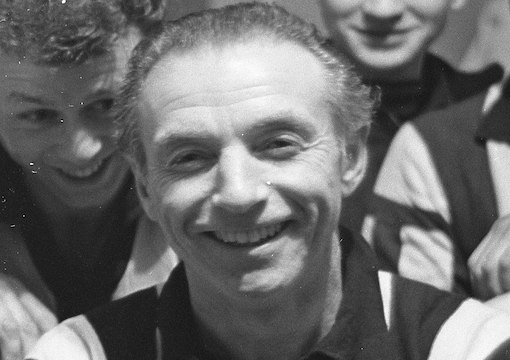

Sir Stanley Matthews

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Sometimes I think of football (soccer), though I have no interest in it. This is because it obtrudes itself on me and is of great cultural significance. I once worked it out that so-called serious British newspapers devote more space to it than to any other matter, whether it be a political crisis, foreign affairs, or an economic implosion. David Beckham was surely a catalyst of the mass self-mutilation that has swept the world in the past couple of decades.

As a boy, I loved football. “My” team was Chelsea. In those days, now long off, Chelsea Football Club was not the slick commercial operation owned by a Russian oligarch that it is now, but ramshackle and somewhat down-at-heel. Its team never won a trophy and was famed for its unpredictability. It would perform brilliantly one match and abysmally the next. I suppose this was appropriate for a team that bore the name of an area in which there were many bohemians, though bohemianism has now been expunged from the earth as a way of life consequent upon the rise of property prices.

In those days—that might as well be 300 B.C.—professional footballers received a maximum wage, if they were lucky, which was not very high: perhaps as high as that of a skilled worker or clerk. After the match, they went home on the bus, and if they were not locally born, as often as not to the care of a landlady, half mother to them and half exploiter.

Of the personal lives of even the most famous of them we knew nothing. They did not drive yellow Ferraris that they crashed into trees, buying another on the morrow. They could be famous, but they were not celebrities. Pictures of them appeared on cards inserted into cigarette packets, which boys collected and stuck in albums. Boys sought their autographs and adulated them, but as the English expression goes, fine words butter no parsnips.

The football pitches were frequently terrible and turned at once into glutinous mud in the rain. The football was of leather and absorbed water, so that kicking it must have been like kicking a dumbbell. Heading the ball repeatedly, as some players did, caused brain damage, and many players died with dementia, many more than could have been expected by chance.

Their post-football careers were often undistinguished and frequently tragic. They had accumulated nothing by the time they retired from the game and had to seek employment elsewhere. Usually they were uneducated and unskilled at anything else. They took jobs in declining industries; some became managers or trainers, but often they slid down the hierarchy of clubs and ended up training teams that were only semiprofessional. Quite a few became publicans or ran sports shops; they were among the more fortunate ones.

The tickets were cheap and the crowds were large, much more proletarian than they are today, and on the whole better behaved, almost even genteel. Expletives were far fewer, and when the referee made a decision against the home team, the crowd would exclaim, “Referee!” When you look at pictures of the crowds of those days, you see people much more civilized than they are today, though the wealth of crowds has increased enormously.

I had my favorites among players, and one of them was called Frank Blunstone. I was delighted to read on Wikipedia that he is still alive, age 86. He was a brilliant dribbler of the ball, evading tackles wonderfully, though it has to be admitted that his artistry often led nowhere as far as scoring goals and victory were concerned. His was virtuosity almost for its own sake, but on occasion he could turn a match around. I admired him all the more because of his inconsistency. At the time I considered him an aging, almost an old, player, and was surprised to learn that he retired from playing when he was 30. How ancient 28-year-olds seem to 12-year-olds!

When I look at the faces of the players then, they seem to me to have more character than those of the players today. Most of them had probably known hardship: They were working-class and had lived through the war. They looked well-turned-out, decent young men. A picture of the Manchester United players on the eve of the famous Munich air disaster of 1958, in which eight of them were killed, shows a group of modest young men enjoying themselves in a quiet way.

Of course, the game as a spectacle has improved no end. The pitch never turns to glue, the ball is much lighter, the football boots are more like ballet shoes than the clod-hopping boots of my childhood, which I remember had to be softened and made somewhat more pliable by something called dubbin. It was a wax that you had to work into the leather; without it, the boots would chafe, even through thick woolen football socks, and you would end up with blisters or excoriated skin.

The players are much faster and fitter now, and are much more skillful, than they were in my childhood, perhaps because the conditions in which they play allow or encourage them to be. You rarely see them at the end of a game with the signs of complete exhaustion that players in my childhood often exhibited at the end of a game, even though they have run much farther and faster.

This is progress, at least technically, if not morally. Perhaps my memory is at fault, but I remember that the players in my childhood were less bad-tempered, slower to anger, than they are now. Of course, when you play for a maximum wage, there seems to be less at stake, the honor of winning being the only extra reward. The greatest football hero I remember having watched play was Stanley Matthews, a man who had started his professional career in 1932. Though the son of a boxer who wanted him to pursue the same career, he was a natural gentleman who never fouled, never cheated, never questioned a referee, and remained modest despite world fame. When, age 70, he injured his cartilage playing a friendly game, he wrote that his promising career had been cut tragically short. When he died, age 85, practically a third of the population of his native city, Stoke, turned out to pay its respects. This was fame, not celebrity.

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest book is Around the World in the Cinemas of Paris, Mirabeau Press.