September 20, 2012

For Japan, which never went through any sort of “de-Nazification,” there is currently a surge of nationalism that is not restricted to its traditional adherents. In addition to maintaining traditional Imperial ceremonies and Shinto’s role in public life (including government officials at rites in controversial shrines such as Yasukuni and Meiji), this movement calls for revision or denial in the way that school curricula and society view such episodes as the Rape of Nanking and the comfort women. Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda must somehow placate these views, especially in light of the upcoming election he faces. But they drive the Chinese and Koreans crazy.

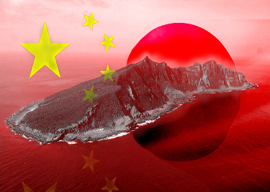

The Chinese have a lot over which to be driven crazy, and the dispute with Japan serves to let off a great deal of steam over internal problems. On the mainland, October will see enormous changes as seven of the nine politburo members step down at the 18th Party Congress; this will be mirrored by alteration in presidency and premiership at the National People’s Congress the following March. Traditionally, such changeover periods have been unstable. In Taiwan the Kuomintang, back in power after eight years in the wilderness, is anxious to retain both its Chinese roots and Taiwanese relevance. Both Chinas tacitly cooperate in upholding mutually agreed upon territorial boundaries. In either case, Chinese nationalism must be served, for very different reasons. Since Japanese apologies over wartime misdeeds are not forthcoming, saber-rattling over the islands will do.

The Koreas face similar identity issues to China, exacerbated by both North Korea’s basket-case nature and the memory of outright colonial status under Japan. MacArthur probably did South Korea no favors by not reviving the country’s monarchy in 1947, though it has come into a strange sort of half-life via palace restorations and the revival of military and religious rituals. As with China, internal divisions can be assuaged by trying to twist the Japanese tail. North Korea may also feel the need to reassert its independence in the face of mainland China’s threats over Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal. The North’s creaky economy may stimulate either revolution or conflict with South Korea to stem off that possibility. But in the meantime joining Seoul in its struggle for the islets gives a veneer of pan-Korean unity and deflects Japan’s annoyance over the kidnappings.

Despite their shared cultural and religious background, with its heavy Buddhist influence and mutual reverence of the Confucian scholar-gentleman, the three peoples’ interaction is reminiscent of Europe. China, a major continental power with an ancient culture its neighbors revere and more recent political weaknesses they despise, plays the role of France. Japan, an island empire obsessed with trade, is Britain. Korea, alternately conquered or influenced by the other two, is Ireland. Whereas the two World Wars obliterated nationalism’s fires in Western Europe, in Northeast Asia they burn as hotly as those of Europe did in 1914. A wrong step by someone and an obscure little island may one day acquire as much notoriety as a certain dumpy provincial town in Bosnia.