September 01, 2021

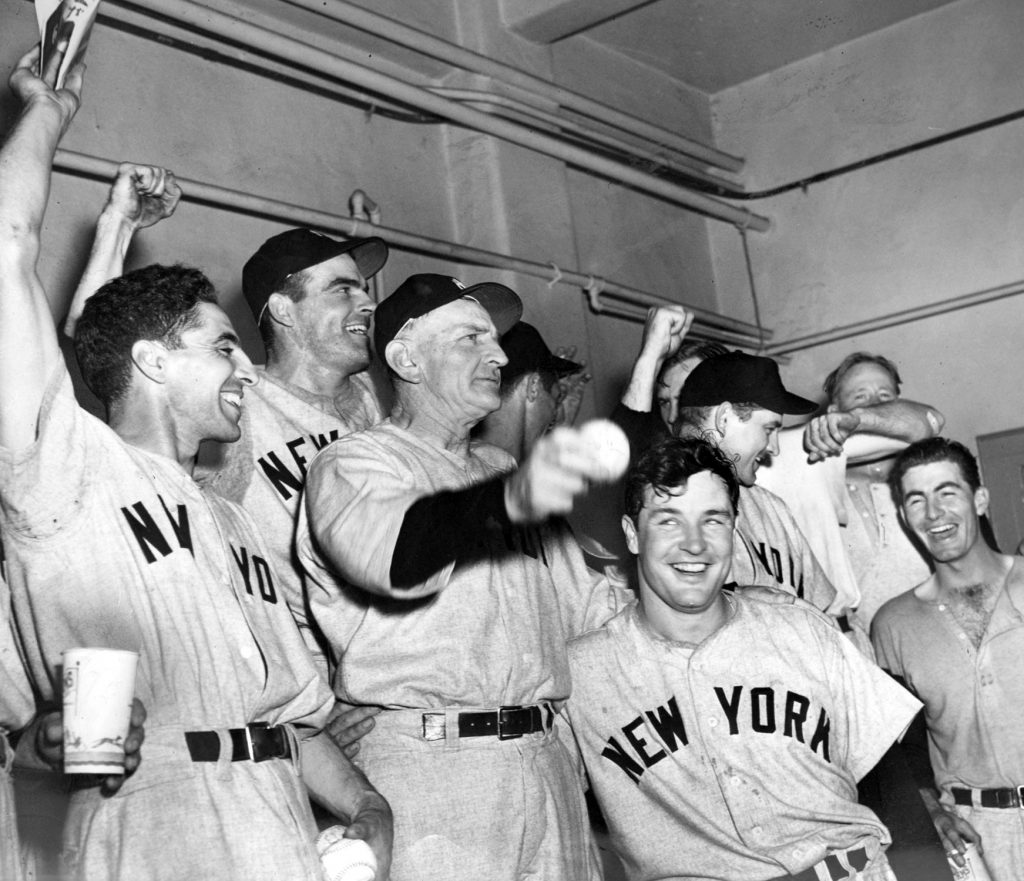

Stengel's Squad

Source: Baseballhall.org

How seriously should whites take the ever-increasing levels of racial hate expressed toward them in outlets such as The New York Times and Washington Post?

Perhaps the fad over the past eight years to express fear and loathing of “whiteness” (i.e., whites) will always be more bark than bite?

After all, most people find themselves angriest not at large-scale abstractions such as a race but with the individuals who get on their nerves.

And other people like to watch spats.

For example, what really drives social media engagement are feuds between even the most minor online personalities, even though they are often more or less on the same side politically. For example, if I want to get a lot of retweets on Twitter, all I have to do is put down David Frum or David French.

Similarly, rappers devote much less energy to hating white people than to hating other rappers. That’s why aspiring rappers are also often expiring rappers: As Robert Heinlein might say, an armed impolite society is a lethal society.

Overall, in murders committed by black known offenders, about four-fifths of their victims are also black. Why? One reason is that the kind of black guy who brings an illegal handgun to a party doesn’t get dissed by many whites because he doesn’t get invited to too many parties with whites.

Of course, every human society has always been riven by interpersonal disputes. The Iliad, for instance, is about that time Achilles got mad at Agamemnon over a girl.

But cultures differ in how publicly they celebrate personal grudges. My impression is that post-WWII America was unusually insistent on hushing up internal organizational antipathies.

It’s a hard subject to document, but I’ll look to baseball history for evidence, in part because this was highly influential on New York high school ballplayer Donald Trump.

The New York Yankees, the dominant team of the 1950s, were celebrated in Life magazine in 1958 as “The Organization Men of Baseball,” the sporting equivalent of IBM’s white-collar minions in button-down shirts:

By now American business thoroughly appreciates the organization man…. The company fosters and molds the organization man who, as a result, finds himself more comfortable, more important and less of an individual. But though baseball is big business today, only one team has exploited the organization man…the New York Yankees.

The Yankee players were admired by the press for not complaining to the press when their famous manager Casey Stengel would bench them due to his arcane but no doubt brilliant strategies.

In reality, Stengel was an increasingly incoherent old man who had let his success go to his head and thought his hunches and whims about whom to play today were proof of his genius. The 70-year-old Stengel was fired after losing the 1960 World Series for not bothering to pitch Hall of Famer Whitey Ford until the third game. (Stengel went off to manage the new New York Mets, the losingest team of the 20th century.)

In the 1960s, the Los Angeles Dodgers succeeded the Yankees as the most copied franchise. The Dodgers took the Yankees’ corporate line to an even higher level of conformity. Each Dodger was trained to deny to the press any rumor of clubhouse conflict.

The Dodgers’ 1980s slugger Pedro Guerrero, who was later acquitted on a drug-dealing charge on the grounds that his IQ, said to be 55, was too low for him to have a guilty mind, was a rare exception. Pedro sometimes had a hard time remembering what each day’s official spin was, so he’d often just tell reporters the plain truth. (I’m a Guerreroist: Like Pedro, I find the truth easier to remember.)

In the 1970s, George Steinbrenner bought the Yankees and adopted a new no-publicity-is-bad-publicity policy of feuding in the tabloids with his manager Billy Martin and star players Reggie Jackson and Thurman Munson. This struck many fans used to the Dodger way as unseemly, but New York journalists extolled the public backbiting as appropriate to the new openness following Vietnam and Watergate. The young Donald Trump was enthralled and came to see Steinbrenner as his mentor.

Over time, this approach spread. For instance, legendary Chicago comic DJ Steve Dahl, organizer of Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park, would spend much of his daily shift complaining about his radio station’s management.

On the other hand, as the tumultuous ’60s disappeared into the mist of times, the upper reaches of society slowly became more genteel again and the Steinbrenner-Trump approach came to seem déclassé.

Institutions fought back by perfecting the techniques of access journalism, so reporters became less swashbuckling than in the Woodward and Bernstein days and more acquiescent to doing their assigned role in propagating the narrative.

For instance, the press spent the first seven months of the Biden administration explaining, rather like sportswriters covering Stengel’s Yankees, how it was such a well-tooled machine of complete competence that there was no need to inquire into distasteful trivialities like just how mentally sharp the elderly boss was.

Of course, whatever the culture demands, people, being people, are still obsessed with office politics. And the growing feminization of organizations means that staffers are even more inclined these days to take everything personally rather than philosophically.

Moreover, Steinbrennerism works only if you have juicy gossip from inside the Yankee clubhouse or some other interesting organization to retail. Most of us work instead at something more equivalent to the Scranton office of Dunder Mifflin. But we’re still itching to tell the world about that awful person we can’t stand.

How to square the circle of indulging in the kind of petty grievances that most fascinate people with upper-middle-class disdain for Trump-like feuding? And how to make our pique sound important?

The answer to both appears to be to position one’s personal gripes as part of the cosmically important war on racism and sexism, while conversely labeling Trump’s obviously individualistic feuds as racist.

Thus, the upper reaches of society have been egging on everybody who isn’t a straight white male to dredge up and dwell on ancient memories of social unease in middle and high school. But instead of getting too specific about that mean girl in eighth grade who said snippy things about your shoes, you are encouraged to blame your embarrassing memories on whiteness in general.

For example, from a New York Times article about the racial reckoning at the most expensive prep schools in the country:

In the wake of the police killing of George Floyd, Black private school alumni formed Instagram accounts: @BlackAtTrinity, @BlackAtDalton, @BlackAtBrearley, @BlackAtAndover and @BlackAtSidwellFriends. The posts are anonymous and difficult to fact-check. But the ache and hurt are inescapable…. A Black Brearley graduate wrote of being conditioned to believe “white skin, straight hair, a skinny body and money was the only way I could be right in this world.”

Rather than tell our most privileged preppies to grow up and get over their adolescent slights, our elites demand ever more such dusty personal umbrages reconceptualized as “anti-racist” (i.e., racist) hatred of white men:

These kinds of stories, taken together with shifts in the culture around racism, persuaded private school leaders to double down on antiracist education.

In summary, people mostly hate other people they know. The growing antiwhite racism works by giving some superficial coherence to nonwhites’ nearly random junior-high interpersonal resentments.

This will all end in tears.