November 01, 2023

Lagos, Nigeria

Source: Bigstock

“The World Is Becoming More African,” trumpets The New York Times, only eight years after I started warning that the United Nations’ projections for sub-Saharan Africa’s population growth suggest a massive problem by the middle of this century, one that is comparable in scale to climate change but is being talked about orders of magnitude less often.

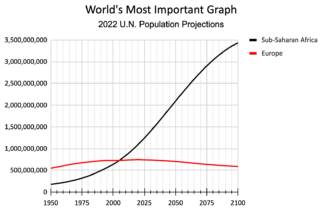

In a decade when fertility is plunging worrisomely in competent countries like South Korea, Africa appears set to grow rapidly for decades, promising the world a blacker future. Here’s my 2022 version of the World’s Most Important Graph:

Of course, the future is unwritten. I wrote in 2015 about U.N. estimates that the sub-Saharan population would continue to soar through 2100:

Africa is almost certainly not going to add over three billion residents over the next 85 years. Something else will happen instead, ideally a decline in African fertility to sustainable levels rather than mass migrations or a rise in the death rate.

The prospect of an endless flow of surplus Africans into Europe’s great cities, turning Barcelona into Baltimore and Salzburg into St. Louis, is depressing, to say the least.

Subsequently, I noticed that hyper-elites like French president Emmanuel Macron and former Secretary of State John Kerry also appear worried about the African population explosion. But even they were having a hard time bringing up the looming menace of too many blacks for fear of sounding racist.

For example, when Bill Gates did a 2018 interview with establishmentarian journalist Ezra Klein, a Vox tweet promoting their talk—

One of the biggest problems the world is facing: rapid population growth in Africa.

@BillGates explains why—and what it will take to turn it around—on Monday’s episode of the #EzraKleinShow.

—was yanked almost immediately due to criticism that it was racist to view high African fertility as a problem.

Finally this weekend, The New York Times looks like they are making a concerted effort with a multipart series about “Old World, Young Africa” to bring media and public attention to the fact that sub-Saharans are on track to replace much of the world’s population.

As I’ve pointed out before, many veteran New York Times writers, such as Declan Walsh, the white guy who is the NYT’s chief Africa correspondent, often want to do a good old-fashioned job of informing readers about important facts. (Granted, the younger diversity hires mostly seem to want to talk about their hair.) But the marketing department no doubt warns them that the Times’ 9.7 million subscribers don’t want to read too much truth. Instead, they mostly want to hear reasons that they are right and their enemies are wrong, that they are on the side of Good, not Bad.

Blacks, for example, are Good. Hence, the more the better, logically.

So, the opening article in The New York Times’ series on Africa’s “youth boom” begins with a dose of happy talk, such as, “As the world grays, Africa blooms with youth.”

But buried further down are some disturbing facts. The few readers who make it to the 28th paragraph are informed:

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, is already deeply stressed: Nearly two-thirds of its 213 million people live on less than $2 a day; extremist violence and banditry are rife; and life expectancy is just 53, nine years below the African average. Yet Nigeria adds another five million people every year, and by 2050 is expected to overtake the United States as the world’s third most populous country.

Then in the 43rd paragraph, the NYT gives subscribers permission to worry. It’s not just Bad People who are troubled; so are Experts:

Africans are rightfully cautious of foreigners lecturing on the subject of family size. In the West, racists and right-wing nationalists stoke fears of African population growth to justify hatred, or even violence.

But experts say these demographic predictions are reliable, and that an epochal shift is underway. The forecasts for 2050 are sound because most of the women who will have children in the next few decades have already been born. Barring an unforeseeable upset, the momentum is unstoppable.

But then the NYT reverts to upbeatness about how Africa is becoming a “cultural powerhouse,” citing Rema’s song “Calm Down” that was popular with fans at last year’s soccer World Cup in Qatar.

“By 2030, Africa’s film and music industries could be worth $20 billion and create 20 million jobs, according to UNESCO estimates.”

Well, 20 million jobs sounds good, but if they only pay $1,000 per year…

But then, the NYT notes, there’s the “Jobs Crisis”:

“Not long ago, technology was the big idea for enabling Africa to leapfrog its way out of poverty.”

It’s not unreasonable to think that Africans will someday make a lot of hit records, just as African-Americans have. I’ve wondered what was taking them so long ever since I spent the summer of 1981 listening to my West African officemate’s African pop mix tapes. (Here’s South African singer Miriam Makeba on The Ed Sullivan Show way back in 1967 singing her Billboard Top 12 hit “Pata Pata.”) African pop just lacked the rock star firepower of the world-conquering music from America, Britain, and Jamaica. African music back then tended to be more communal than egocentric, in contrast to the Atlanticist Elvis-Jagger-Marley-MJ-Bono rock god tradition. (I’m old now, so I don’t know anything about current pop, African or otherwise. But I wish them well.)

But if African-Americans haven’t done much in tech, why did anybody assume Africans would?

Nor is Africa doing much in the way of old-fashioned factory work: “Africa’s share of global manufacturing is smaller today than it was in 1980.”

Finally, in the 83rd paragraph:

And the baby boom endures, smothering economic growth. Other regions, like East Asia, prospered only after their birthrates had fallen substantially and a majority of their people had joined the work force—a phenomenon known as the “demographic transition” that has long driven global growth.

Moreover, sub-Saharan politics have taken a turn for the worse in recent years, with coups making a comeback. The worst political trouble, both in terms of military coups and Muslim crazy men, is seen lately in the Sahel, the unforested but habitable belt south of the Sahara, which, not coincidentally, has the highest fertility. The Times notes:

“The Sahel leads the world in two ways. It is the global center of extremist violence, accounting for 43 percent of all such deaths in 2022, according to the Global Terrorism Index. And it has the highest birthrates—on average seven children per woman in Niger and northern Nigeria, six in Mali and Chad, and five in Sudan and Burkina Faso.”

Hence, in the Sahel, enlisting in the schoolgirl-kidnapping Boko Haram is not just an adventure, it’s a job:

Instead, researchers found, the single biggest reason for joining a militant group was the simple desire to have a job.

Perhaps Africa’s essential political problem is that its culture breeds lots of young men, but it also tends to reserve power for old men, possibly due to a tendency toward gerontocratic polygamy. For instance, my West African friend, a man of careful planning, intended to supplement his current wife with one additional bride each decade he lived, up to a maximum of four. (He was not a Muslim, but he approved of the Prophet’s prudent moderation in such matters.)

Hence, when Robert Mugabe was finally overthrown at age 93 after 37 years in power, he was 75 years older than the average Zimbabwean.

It’s no continent for young men.

Now, there are also reasons for some degree of optimism. For example, when the U.N. last forecasted Africa’s 2100 population in 2022, it cut its projection by 9 percent from its 2019 guesstimate. In truth, nobody has a clue what the population will be that far out. (On the other hand, its 2050 forecast barely fell.)

And sub-Saharan Africa’s total fertility rate is declining steadily: by one estimate, from 5.2 babies per woman per lifetime in 2011 to 4.6 in 2021. If its TFR continued to drop 0.6 per decade, it would reach the replacement rate around 2061 (but the total population would continue to rise until the end of the century due to “demographic momentum”).

Fortunately, sub-Saharan Africa is not yet all that densely populated, so it should be able to grow more food. Africa tends to have mediocre soil, but in enormous amounts. McKinsey estimated in 2010 that Africa had 6 million square kilometers of not-yet-cultivated farmland, 60 percent of the world’s total. Mercator projection maps, by understating the size of equatorial regions, give people the wrong impression that Europe is fairly capacious compared with Africa.

One common misapprehension is that Africans aren’t cut out for farming because they were hunter-gatherers until a few generations ago. But that’s mostly true just of rarities like Pygmies and Bushmen. Instead, most Africans (and African-Americans) are descended from dozens of generations of Iron Age agriculturalists. That’s one reason Southern plantation owners in the early U.S. considered blacks much better farmworkers than Amerindians, who in North America tended to be not many generations, if any, separated from hunters. So, Africans are by no means hopeless at farming, especially if the men were to shoulder a larger share of the toil.

And technology is making it easier for even African villagers to get up to a minimum standard of living: enough electricity to charge your smartphone. While South Africa is having trouble keeping its legacy electrical power grid functioning 24/7, Africa has no shortage of potential solar power that can be tapped on the spot without maintaining a complex network.

The Gates Foundation has two main strategies for reducing sub-Saharan fertility, and both sound reasonable: increased education of girls, and a malaria vaccine to change the culture so that parents don’t want so many spare children to replace the ones who will die of malaria. (Of course, the moderately effective malaria vaccine is likely to initially boost population growth before the hoped-for cultural change settles in.)

It’s also important to stop rewarding African excess fertility with immigration to Europe and, lately, America.

Mauritanians from western Sahel have been showing up by the thousands at the Mexican border this year. They get to America via a circuitous path through Nicaragua. Apparently, the leftist Central American country’s president, old Sandinista Daniel Ortega, is getting his revenge on us gringos for the 1980s U.S.-sponsored Contra insurgency against him by foisting Mauritanians on the U.S.

But The New York Times can’t help itself from ending its worrisome reporting on the African population explosion with joyous spin:

This year’s surging turmoil—new crises, new wars and new economic slumps—would give pause to the greatest of optimists. Yet there are also reasons to hope.

“I tell my friends in England that the time will come when they will put out a red carpet for those guys now coming in boats,” said Mr. Ibrahim, the philanthropist.

African countries have a vital resource that aging societies are losing: a youthful population brimming with energy, ideas and creativity that will shape their future, and the world’s.

We shall see.