January 28, 2015

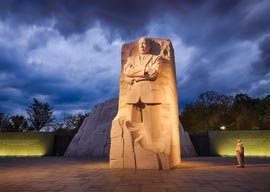

Martin Luther King Memorial, Washington D.C.

Source: Shutterstock

It’s widely assumed, both by liberals and conservatives, that the fields of arts and entertainment innately induce egalitarian political leanings. Much of the prestige of the left, in fact, derives from the notion that it’s only natural for creative people to favor equality above all else.

Granted, there are a handful of obvious public exceptions, typically ornery senior tough guys, such as Republican Clint Eastwood. His American Sniper, with its monumental star turn by Bradley Cooper, is now on track to being the biggest movie released in 2014. This would make American Sniper the first movie for grown-ups to lead a year’s box office tally since 1998, when Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan was tops.

Out-of-the-closet anomalies like American Sniper drive the liberal press crazy with fear that they are losing control of the media.

One possibility is that artists and entertainers are less monolithically on the left than you might think, but are kept in line in public by stifling peer pressure.

For example, by now Spielberg ought to have earned himself a fair amount of deference from his fellow liberal Democrats for being a credit to his political persuasion. But even he doesn”t seem able to admit that his upbringing in the red state of Arizona saddled him with a lifelong love for guns.

Here’s the only known photograph on the web of Spielberg shooting a gun.

You”ll notice it’s an extraoardinarily expensive one. Like a British duke in 1913, Spielberg has assembled one of the world’s finest shotgun collections. He commemorates each movie he makes by buying himself a six-figure shotgun, then having an Italian master craftsman spend a year suitably engraving it. It’s an elegant hobby, but one that Spielberg can”t talk about. Perhaps it would raise doubts about his work: Are his best movies really as homogeneously liberal as they are supposed to be?

A more subversive theory is that art is inherently anti-egalitarian, that the entertainment industry thrives by elevating individuals to levels of mass adoration that Belshazzar of Babylon would have found excessive. In turn, the entertainment industry adopts a bogus ideology of promoting equality to cover up its essential tendency toward Caesarism.

For example, this combination of exhortation and megalomania has been apparent for 99 of the 100 years that Hollywood has been making epic films.

Early March will mark the 100th anniversary of the original box office smash, D.W. Griffith’s denunciation of the rape culture of the Reconstruction Era, The Birth of a Nation. Stung by criticism from the NAACP, Griffith released in 1916 a more politically correct and even more ambitious blockbuster, Intolerance. It retold four stories of bigotry and oppression, from ancient Babylon down to the present day.

I”m sure that everybody has taken Griffith’s sermon against intolerance deeply to heart, but, honestly, the only thing anybody remembers from the movie is the Babylonian set that Griffith spent his Birth of a Nation profits constructing.

To give tourists snacking at the food court at the Hollywood & Highland Center shopping mall (which hosts the Academy Awards annually at its Dolby Theatre) a fittingly cinematic experience, the developer rebuilt some of Intolerance‘s elephant god monuments. These things are almost as big as that Chinese statue of Martin Luther King, Jr.“which itself looks like the kind of cross between Ozymandias, Chairman Mao, and Mike Tyson that we”re not supposed to notice is an aesthetic blot on the National Mall in Washington.

But certainly, we rapidly outgrew such excess, right?

I”m not so sure.

During the Great Depression, Frank Capra directed movies about plucky little guys standing up to the big shots. But when casting his plucky little guys, Capra tended to pick James Stewart, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, or Cary Grant. And when Capra wrote his autobiography, he called it The Name above the Title.

Consider the most academically acclaimed movie of all time, Citizen Kane. I”ve read countless explanations of how it’s an important warning about the menace posed to democracy by William Randolph Hearst. But, come on, everybody really loves Orson Welles” big man act. Welles, as he liked to explain, was a “king actor.” He had to be the highest-ranking figure in a scene or audiences would wonder why he wasn”t in charge.

Intellectuals have done much to egg on genius worship. For example, Hollywood movies of the 1930s and 1940s tended to be made by large organizations using careful division of labor. But the young French critics at Cahiers du cinéma, rebelling against the dominance of Communist intellectuals in Paris, explained that if you looked at American films just right, you”d know that the director was the true auteur and thus Hollywood studio movies are monuments to individualism.

Their auteur theory was de Gaullism avant la lettre: enlightened autocracy validated by occasional popular approval. When Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958, he had his culture minister, André Malraux, find him some young artists who weren”t Communists to subsidize to make France look good. The French New Wave critics-turned-directors were de Gaulle’s chief beneficiaries.